INTRODUCTION

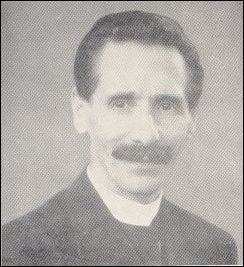

Former Saron miner Brin Daniel (1912 -1994) pictured in 1992 aged 80. For some reason many historians mistrust the words of those who participate in history and bear witness to it – the so-called ordinary people – contemptuously describing such testimony as anecdotal or subjective. Such historians prefer instead what they define as the objective facts found in official records and accounts, as if these are somehow less subjective and free from bias.

Of course, even the official version has to be written by someone and it is difficult to believe that kings and queens, politicians or generals are going to be scrupulously fair in their recording of what happened. And even if they employ others, as is usually the case, to write such history for them – the official scribes like journalists, academics and other members of the establishment – these are hardly going to be free of this taint of partiality either. If anything, they are more likely, not less, to present events to their own advantage – those who pay the piper call the tune, as the proverb goes. It has been observed, with justice, that only the winners get to write the history of wars and it's no different with the history of peace either.

Although history is made by the countless ordinary people of the world, it is the 'great and the good' who somehow get their names in the history books – and all the money as well. And wherever they appear, they manage to position themselves centre stage. The rest, if they appear at all, get relegated to the footnotes of history.

Here, then, are just two of Ammanford's 'footnotes', in their own words, spoken and written by themselves, to redress the balance just a little. Then, after the words of Brin Daniel and Edward Glyn Cox, there follows the story of another ordinary miner from Ammanford, Olwyn Hughes, whose tale can be set beside the other two.

1. THE DOLE SCHOOL – UNEMPLOYMENT IN AMMANFORD IN THE 1920s

by D Brin Daniel (1912 – 1994)The worst period in the history of the Amman valley was during 1928 - 1930 when there was some eighteen months of almost total closure of the valley pits. This was the period of the Dole School, better known to the attenders as "The College", as we rode to and from the Dole School on the same bus provided by the authorities for the local Grammar school's middle class children.

......I was an odd man out in this situation. After leaving school at fourteen after the 1926 strike, I worked for some time as a shop assistant before taking work at Saron Colliery. When Saron Colliery was closed early in 1928 I found myself on the dole. On presenting myself at the Ammanford Labour Exchange I was instructed to attend the newly opened unemployed school at Tirydail near Ammanford. I was registered as unemployed and given a bus ticket for my transport to school with a warning: no school attendance, no dole.

...... The following Monday morning I, along with quite a crowd of youths from all over the valley, turned up at the school. It was murder. The headmaster prayed for us, we sang a few hymns, then a local preacher gave us a talk on how thankful and obedient we should be to the providers of these blessings to us poor mortals.

...... We were then formed into groups and allocated to various teachers. No interview, no discussion on ability or interests, but just moved around like sheep from one room to another. Thus passed our first experience of education on the dole. By the following day some of the lads had brought along packets of playing cards. That's one thing I did learn – how to play various card games and how to cheat when necessary.

...... On the following Friday, a person from the Labour Exchange came along. We signed his book and were paid our dole money. On leaving his room I found out that as some boys of my age had been paid various sums of money, I had been paid only five shillings.

...... I returned to this clerk for explanation and was told that as I had only paid for a certain number of benefit stamps in one year, I only qualified for five shillings and that for only six weeks, and there was nothing that could he done in this matter. I decided to attend school for six weeks and then – no dole, no school attendance.

...... The following week we were graded, not by ability, but by name, to various courses and allocated to our tutors, who, it turned out, knew no more than we did about the crafts they were supposed to educate us on. As our age group was from sixteen to twenty one it became clear that the older lads in the school would be given the most privileges in any training that was possible in this overcrowded education centre which served the whole of the Amman Valley and surrounding villages with the mass youth unemployment problem that prevailed in the locality.

...... Sure enough that's what did happen. Boys over eighteen were sorted out from the lower age group, and after some tests the dead-ends of that group were returned to the under eighteen group, judged as dead losses. The sixteen to eighteen group was then formed in classes with little to do but wander from classroom to classroom wondering what would happens next.

...... Eventually, we were allocated to a craft master, games master and an English and Maths master, the same two persons really. All we changed were the rooms for these courses.

...... On the Monday morning of our second week at the Dole School we were presented with a sight to remember. Instead of the usual assembly routine of prayer, short talk and instruction from our headmaster, there on the platform was our headmaster, the teachers, a local preacher and the manager of the Labour Exchange. That morning our prayers were led by the preacher, as was the short talk on the blessings showered upon us by our caring benefactors.

...... Then we sung the hymn 'Guide me O thou great Jehovah', very appropriate, for if any group of persons needed guidance we were that lot.

...... As Welshmen we dug into the singing, especially the bit about pilgrims through this barren land, for pilgrims we certainly were in a pretty barren land.

...... To cap it all we lad a long talk from the Exchange manager himself who exalted the benefits showered upon us by the government and the good people who had sacrificed for our benefit.

...... It was up to us now to return their goodness by study and hard work. After this we all trooped out like a lot of willing monks to our class rooms.

...... When our teachers arrived at our classes, more momentous news. We had all been graded for our ability and selected for training in suitable crafts. I, along with a friend named Idwal, were to be trained as future carpenters. When Idwal heard this he at once suggested that we learn all we could in this craft so that we could start up a funeral director's trade in the village – a trade an uncle of his had made quite a good living at. Also, as Idwal claimed, the only expanding trade in the valley.

...... I promised to think about this. By this time our teacher had us marched out Into the carpenter's workshops. We had never seen such an array of tools and timber. I thought Idwal's idea had some hope. But as I had only six weeks In which to learn before my dole would be stopped, I did not place my hopes on this.

...... We were presented with lead pencils, rulers and a plan of what we were supposed to set to task to produce – a soap holder which could hang on the bathroom wall.

...... As few houses in this locality had even a proper bath, let alone a bathroom, the project looked pretty gloomy.

......Our teacher left the room taking two at the lads with him. On his return he and the lads were loaded with strips of plywood and nails, which they distributed among the class. I looked at Idwal, thinking, there's not the timber here for the coffin trade idea."2. POEM – BETRAYED by Edward Glyn Cox

Betrayed

An historette on "Dust"

Edward Glyn Cox

Great Mountain NUM Lodge Secretary.Along the garden path he goes,

More slowly now of late.

He lingers near a faded rose

That droops inside the gate.

'Tis there to vent the stifled sighs

No weary heart can hold.

For, like the rose, he fades and dies,

But not from growing old.In yester years he was content

To work still more and more.

But now his passing hours are spent

Around the kitchen door.

No hope for him lies near at hand

The future, deep despair.

For no one seems to understand,

And no one seems to care.Since last he walked along the street

It seems just like an age.

Shuffling along to a corner seat,

His garden now a cage.

Deep in his thoughts he sits alone,

Life's bitter fruits to taste.

Though giving all while in the pit

Now thrust aside to waste.'Twas there he toiled in blinded trust,

But what a thankless role.

In doing so breathed in the dust

That kills in digging coal.

He never held himself to ask

Can this or that be wrong?

But spared himself to neither task

And did them everyone.Now many things he is denied

And countless joys he yields.

The walk along the mountain side,

The ramble through the fields.

Maybe you'll romp on sandy beach,

Or bask there in the sun,

Then climb to nests far out of reach:

He, too, once called this fun.An effort on your part can pave

The path that twists and turn.

It's not too much for what he gave

To dig the coal you burn.

Forgotten is the price he paid

To build this Nation's wealth.

Forgotten now, he sits betrayed

With but his failing health.So soon his days draw to a close;

Their course is set and sure.

For like the faded drooping rose

There is no means of cure.

While this goes on, we all complain

About the coal, the cost.

Without regard for endless pain

And loved ones dearly lost.No more to laugh, to smile or sing:

Those are but idle dreams.

If this is life, death has no sting,

It's best to die it seems.

Do seek him out and play the host;

It's thoughtful, helpful, kind.

Ease him where it hurts the most:

Within his tortured mind.3. HOW ARE THE MIGHTY FALLEN – by D Brin Daniel

During my forty-five years working in the anthracite coal industry I had the good fortune to meet some of the most interesting people employed within the industry in the Amman Valley. Interesting by the fact that these men, owing to their ages, were among the grass roots of the organizing of the South Wales Miners Federation in the valley. For during the nineteen thirties most of these people were almost in their seventies, some well over, as this was the period when a man was expected to work until he dropped or face the inequity of Parish Relief at the end of his days. Here then we have the true salt of our earth, the people who laid the foundations for the Anthracite District communities and the deep loyalty and community consciousness that prevails to this day within our mining communities.

...... This short history is of but one person, a master craftsman in his time, brought down to the level of a colliery surface worker by the changes in the mode of production and transport which he could not understand or accept.

...... Fred Evans, Fred y Sâr (The Carpenter) to his work mates, was in his time without doubt a master craftsman coachbuilder, wheelwright, painter and varnisher. Along with this were his other trade of carpenter, builder of farm implements such as carts, gambos and other public demands on his trade during the pre-motor car era.

...... Fred Evans was among the most prosperous businessmen in the Amman Valley with his workshop and stores on a section of land behind where the Beynon Garages now stand at the junction of Florence Road and Llandybie Road, at Tirydail, Ammanford. Here at his workshop he employed as many as thirty workmen, craftsmen and labourers as the work demanded. A big employer for such a town as Ammanford during this period.

...... Notwithstanding this prosperity Fred Evans ended his days as a slag picker on Park Screens, a coal preparation plant for the Park and Saron Collieries.

...... How could such a tragedy happen to such a man? The following episode is a factual account of the story Fred Evans related to me when he confided to me the reasons for his downfall.

...... During, the 1930 - 40s, I was working on Park Screens along with Fred Evans and some thirty others. Some changes in the method of coal cleaning was being introduced by the Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries Ltd., to which the workmen objected, as this new method could mean a rundown in the labour force. A matter much discussed and argued over by the workforce, mostly elderly and disabled workmen.

...... During one such discussion, which was rather heated, over the question of changes in the method of production and their relationship to the security of the workers, I had stated that changes in the mode of production were inevitable and not always a danger to job security. In fact, by failing to accept the principle of progress we could be creating the conditions for our own future insecurity. The argument continued for some time until we went back to our work.

...... A short time later Fred Evans came along to me and stated; "Your argument is quite right about this changes business; we could all be losers." As Fred was not politically or otherwise an involved person this statement surprised me so I asked Fred where he got the idea from. He replied from his own experience, and went on to relate his personal experiences as a businessman.

...... During the late 1800s and early 1900s Fred Evans was building up his business. In a short time he was well established at his Yard at Florence Road. The business had prospered to one of the largest within the Amman Valley with a reputation for good work among his customers, from the local farmers to the middle, and upper classes whose carriages, traps and other implements he built, and kept in repair.

...... One morning a stranger called at the Yard Office asking to see Fred. This person introduced himself as a representative of Ford Motor Cars, and that he had been advised to seek Fred's views on the possibility of Fred becoming the local agent for the Ford Company. During the discussion the Ford Representative stated that with the introduction of the motor car on the road, horse transport was on the way out and short lived. This Fred could not accept as in his view horses had served man throughout the ages and would continue to do so for ages to come. So Fred refused this glorious offer.

...... About half a mile from Fred Evans' workshop, another person named David Jones had a similar business on a much smaller scale, in fact almost a one-man establishment. The Ford Agent, after his failure to convince Fred on the future of the motor car and the effects on road transport, left Fred Evans and visited David Jones making him the offer of agency which David Jones accepted.

...... Within a few years the motor car trade increased and the demand for Fred Evans' product diminished. This situation with the falling in his trade caused Fred quite a problem and worry which eventually led to alcoholism and a decline in his business, and finally bankruptcy.

...... Fred now entered the ranks of the wage labourer when the Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries Ltd employed him at Park and Saron Colliery as a carpenter. Fred, however, considered himself one of the elite among workmen, a tradesman.

...... However with the closure of Park Colliery during 1932, Fred's standard was again lowered to the status of a sawyer whose work consisted of the rough sawing of timber for use at the colliery. The final move for Fred was when the Colliery Company stopped this process at Saron Colliery moving all this work to Pantyffynnon Colliery. Fred, owing to his age and lack of call for his trade at the colliery, was now demoted to a slag picker on Park Screens where he ended his working days.

...... His last words to me on this subject were; "If only I had met a person with your views on problems such as changes I would not be where I am today." I replied: "I am sorry Fred; such people with my ideas were to be had even at that time. That is where I got them from, by listening to their views. Unfortunately you would not listen then. And only forced by the circumstances of lowly slag picker to realize that in the eyes of the Amalgamated Anthracite Company, all men are of equal use to the Company. Which is the general rule of our Society.4. A SARON CHILDHOOD – by D Brin Daniel

For children of my age attending the local Council School at the village of Saron, Llandybie, the basic fact of life that our future existence depended upon our ability to work was driven home at an early age, coming up to fourteen in fact. Our aging headmaster at the school used quite a novel method of driving home this point to the boys in particular. It was accepted that the girls' future lay in the drudgery of housework at home or as servants to their betters.

...... During this period our educational ability was measured by our ability to read, write and work our simple arithmetic tables to a standard relative to our ages. Then you could progress from Standard One to Standard Six, more by age than by ability, to pass the elementary examinations. By the time Standard Six was attained most of the students would have reached the age of fourteen and would be leaving school at the end of the term.

...... As the end of term approached, the headmaster would visit the class of the older children and present his method of introducing the class to the world outside. First he would lecture the class on the importance of finding employment on leaving school. Then he would call out the name of a boy he knew would be leaving school and asked the question "What do you intend to do on leaving school?" As coal mining was about the only source of employment in the locality the answer would be "Go under the clod sir." (Down the mine) to which the old master would reply: "A collier, very good indeed." But should the boy reply with any other form of employment, he would be greeted with: "A backward boy like you thinking that he is better than your friends here. You are planning a poor future for yourself as an idler." The only boys to escape this tirade would be the sons of local farmers, the preacher, publicans and shopkeepers.

...... There was one means of escape: promotion to the scholarship class at an early age. This route again belonged to our middle classes, as the parents of working class children could not afford the fees demanded by the Education Authority for higher education at a County School.

...... Anyway, on reaching the age of fourteen, I left school to take my chances in the jungle called employment prospects. On leaving school, much to the concern of my family, I found employment with a local butcher. The agreement was that I was to receive ten shillings a week wages and my food during the day's work. My attraction to this work was that I would be in charge of the butcher's horse, a broken down racehorse named "Mochyn Pwdwr" (Lazy Pig – owing to his activities as a racehorse being rather dubious but quite a happy butcher's drag horse). I was happy being with horses so this work was quite pleasing.

...... I had been at this work for about a month, still waiting for my ten shillings wages, when one evening the butcher asked me to come back that night to help in the slaughter house, something I had never done before. I agreed to help. On returning to the slaughter house that evening the butchers were killing the larger animals, a sight I did not enjoy. On completing this work they drove in some lambs. One was picked out and laid across a bench. Now my job was to help hold down the lamb for slaughter by holding on to the hind legs while the butcher cut its throat. A very distasteful work indeed. Anyway, I held on to the poor creature's legs while the poor lamb bleated pitifully. Suddenly it turned its head looking straight into my eyes bleating for mercy. I let go of the hind legs then pandemonium broke loose. The lamb kicked out knocking the butcher sideways and off it went. I did not stop either. I took up my coat and left for home.

...... The following morning I did not go to my work with the butcher. When he met me later on the road he stopped to inform me that I was sacked, I replied that I had sacked him the night before. Thus ended my experience as a butcher's boy.

...... Later on that morning the grocer who lived next door to my home offered me employment as a shop assistant and errand boy which I accepted for the wage of ten shillings a week flat. Here again I would be in charge of the horse to deliver goods. This work started out pretty good but as the weeks went by the grocer kept finding more and more little jobs to do until eventually I was working from seven in the morning until late in the evening for my ten shillings. Then I was told that the local Co-operative Stores were looking for an assistant. I applied for the vacancy and was employed at a wage of eight and sixpence a week working from nine to six from Mondays to Saturdays with a half day on Thursday afternoon.

...... The house in which I was born "Gwynffrwd" in the village of Saron, Llandybie, still stands on Saron Square, next to the public house "Colliers Arms". This house was built by my grandfather John Daniel, who was fatally injured at the Park Colliery, on December twenty third, nineteen twelve, at the age of sixty-four.

...... An interesting incident in my family history concerns my uncle at Cwmllynfell, "Nicolas y Glais". In his early career as a dentist he was searching for a room to hold a surgery, something he found hard to come by. It was my Uncle Tom, "Twm Llandybie" as he was known locally, who provided Nicolas with a room in his parlour where be held a surgery for years at Cwmllynfell.

...... I was brought up in "Gwynffrwd", my grandfather's home. As my grandmother was blind my mother and family moved in to look after the home. My grandmother was a strong willed person who ruled the whole family, and whose word was law to all from the oldest to the youngest among the family. There were never less than four colliers at home, sometimes seven or eight, as relatives would come along from other districts looking for work in the anthracite collieries. They would stay a while, find work, and move to a village nearer their work, Emlyn, Cross Hands, or Tumble. As my grandmother's family originated from the Llanon area of the Gwendraeth, and also was a large family, it was easy for these stray relatives to find employment in that area.

...... The community of Saron, as typical of mining villages, was a very close community. Interrelationship was common. The Morgans, Bevans, and Davies's being the ruling clans within the village. Practically every other family in the village, including mine, had relationship contacts through marriage with one or other of these families.

...... One of my mother's sisters married John "Bach" Davies, another married Evan Richards, a close relative of the Bevans, and Morgans. This was the general pattern within the community. This appears true also of relationships within the surrounding villages such as Tycroes and Capel Hendre where the same clan pattern existed.

...... One relative, Evan Richards, an overman at Pantyffynnon Colliery, was killed in a tragic accident at that pit during 1928. The Amalgamated Anthracite Colliery Company, by the use of a false witness, succeeded in denying the widow her right to compensation. I have been told by workmen who respected Richards that the false witness was promoted to overman by the Company soon after the Court case decision.

...... Ammanford, considered a town, "pentre", even in the early twenties, contained a more cosmopolitan community. Within this pattern of a mining community life, my early years, even though Ammanford was only two miles down the valley, was limited to the life and activities of Saron community. The chapel, strictly Baptist, the Council School, eisteddfodau, and once a year, escape through the Sunday school trip, when even the most devout deacon would paddle in Swansea Bay. Then there was Gymanfa Ganu at Easter, and best of all roaming the countryside and swimming in the Rhos Colliery pond. Dangerous, so we were told, but the only place where we as children could go to swim in.

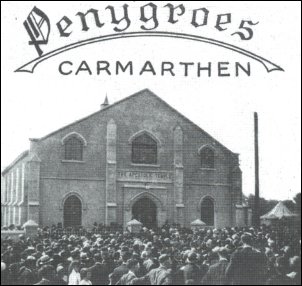

Pastor Dan (D.P. Williams) in later life. My family by name, Daniel, and by their activities, were more or less out of step with the general trends of the community. Firstly, they were staunch Liberals, due to their ties to farming. Secondly, they were members of a way-out religious creed, my grandparents having seen the light during Evan Roberts' 1904 Revival.

...... Thankfully, we as children were not forced to attend at the services of this creed as the nearest place of worship was at Penygroes, some three miles up the valley where another relative by marriage, Dan Williams, "Dan Bryncwar" had organized an opposition group. The Apostolic Church, Dan's split, was a little tin shed across the road from the Mission Hall that my grandparents and their brood had organized. Dan Williams was one of the original supporters of this Mission Hall until, so he claimed, God gave him a call and direction to form the Apostolic Church, a religion with World wide influence even to this day with churches in 52 countries, and which used to hold its annual conference at Penygroes on the first week of August every year.~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Note on the Apostolic Church:

In 2003 the Apostolic Church yielded to the inevitable march of time: the Penygroes connection was finally severed and the conference was held in Swansea University instead. The siren song of modernity has presumably drowned out the voice of history, and modern conference centres, fully equipped with seminar facilities, PA systems, video players, overhead projectors and all that technology can offer, now please the worshipper more.

The final move of the Apostolic Church Convention from Penygroes prompted this letter to the South Wales Guardian of 24th July 2003:

‘Glory came down’ in Penygroes

I am sorry to hear that the Apostolic Church has decided to move the venue of this year’s Convention, held in August, to the University of Wales, Swansea. It is the end of an era.

..... The first Penygroes Annual Convention was held in 1917, in a tent seating 1,000 people. It was billed as being for the ‘deepening of spiritual life.’

..... Because of the increasing number of people coming from Scotland and England, the meetings were transferred to the Memorial Hall, Penygroes, in 1921. But it was not until 1928 that it was officially described as being ‘international’. We remember visitors from Africa and India walking around the village in their national costumes.

..... The move to Swansea means that Penygroes will no longer be the Mecca of the Apostolic Church in this country or abroad. Over the years it has boosted the local economy, encouraged the local chapels, and it has reached out to evangelism in the local community.

..... We pray God’s blessing on this new venture, but we would remind our friends in the Apostolic Church that Penygroes was regarded by Pastor Dan as the ‘Mount of God’ and it was to him the place where ‘the Glory came down’.Post Script

In the archives of the South Wales Coalfields Collection, held in Swansea University, there can be found a small collection of Brin Daniel's papers. While most of these are related to trade union matters and political affairs – there are some on the Vietnam war during the 1970s – we also see these items listed in the catalogue:

° Essay on Dic Penderyn with notes ° Course notes for the National Council of Labour Colleges postal course in English grammar and article writing ° Course notes for the TUC (Trades Union Council) postal course in English ° 1944 – Circular Appeal for donations for the new Stalingrad Hospital in memory of Welshmen who died in the Spanish Civil War Thousands of working people of Brin Daniel's generation, forced to work at twelve years of age, also showed the same determination for self improvement, achieving through evening classes and correspondence courses what they were denied by their education system, while keeping a close eye on the political issues of the day as well.

5. OLWYN HUGHES – DANIEL IN THE LION'S DEN

Background to Ammanford's political history

Before we move on it might be productive to outline the political background operating in twentieth century Ammanford, and especially within the context of the mining industry that sustained the economic and political life of the Amman Valley at that time.

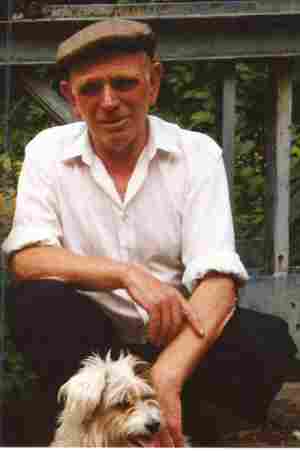

Ammandord miner Olwyn Hughes (1926-1997) In the twentieth century one political party dominated Ammanford's political history: Labour, who held the local parliamentary seat continuously from 1922 to 2001. In the 19th century things weren't quite so clear cut and the Conservative and Liberal Parties contended for what few people had the vote. But increasing industrialisation in the southern regions of Carmarthenshire saw a gradual change in the political dynamic of the county and by the latter part of the 19th century, industrial areas like the Amman Valley tended to vote for the Liberal Party (those few that were given the vote, that is). The agricultural workers, usually under the orders of the local squire who employed them, or were their landlords, voted Tory. Elections weren't conducted by secret ballot until 1872 so the squire knew exactly how his employees or tenants had voted, and reprisals for not voting for his chosen candidate (which might even be himself) could include loss of job, rent increases, or even eviction. By the start of the twentieth century successive acts of parliament had extended the vote to many more people, including some from the working class. The first tentative extension of voting rights had been the so-called 'Great' Reform Act of 1832, and the Second Reform Act of 1867, for example, quadrupled the number eligible to vote. Then there were other electoral reform acts in 1872 (which made ballots, at last, secret and hidden from prying eyes), 1883, 1884 and 1886, so that by 1900 the conditions were ripe for the arrival of a new political party on the scene, created specifically to represent the working class in parliament – the Labour Party.

Within a generation the working class had switched allegiance from the Liberals to Labour, especially after 1918 when women over the age of 30, and women over 21 who owned houses or were married to householders, got the vote as well. Finally, in 1928 all women over 21 were given the vote on equal terms with men. In 1969 the voting age was reduced to 18, and in the same year Northern Ireland, finally, received the vote without the need for property qualifications.

This spelled the end of the Liberal Party as a meaningful force, at least at Parliamentary level. The transition wasn't immediate, however, and the new Labour MPs were too few in number at first to have any significant influence on their own, initially propping up a minority Liberal Government as the junior partner in a coalition. But as the number of Labour MPs in Parliament grew, they soon asserted their independence, replacing the Liberals as the opposition to the Tories by the 1920s, and in 1924 even forming a government with Ramsay MacDonald as prime minister. In the General Election of 1900, the first that Labour contested, they won just 2 seats, but managed 29 in the 1906 elections, rising to 42 in the next election of 1910. In 1918 the number of seats rose again to 57 but it was in the 1920s that Labour made its breakthrough: 142 seats in the 1922 General Election, 191 in 1923, and 287 in 1929. Labour had arrived, and the Liberals have never been a significant factor in British politics since. Ammanford was part of the solidly industrial constituency of Llanelly but curiously Labour weren't able to defeat the Liberals until 1922, the year of their breakthrough at national level.

Thus the politics of the Amman Valley for most of the twentieth century has been dominated by the Labour Party in the same way the Liberals dominated the later nineteenth century. All Ammanford Members of Parliament from 1922 have been Labour and Labour had a total monopoly of power in local councils during the same period as well. Ammanford miner Jim Griffiths became the second Labour MP for Llanelly in 1936. Griffiths, born in 1890, had joined the fledgling Labour Party in Ammanford as an eighteen year old miner. Visits by James Keir Hardie and other socialists had a powerful impact on Griffiths, and in 1908 the young miner became a founder member and secretary of the newly-formed Ammanford branch of the Independent Labour Party (ILP). Labour's political domination all changed in the General Election of 2001, however, when Plaid Cymru took the local parliamentary seat from Labour, just after Labour had also lost its majority in Carmarthenshire County Council. The year 2000 ushered in not just a new millennium but a new era in British politics as well, where old certainties have been cast aside and political loyalties along simple class lines can no longer be taken for granted.

The creation of the Labour Party in 1900 co-incided almost exactly with the birth in Wales of another important organisation of the working class – the South Wales Miners Federation (SWMF) or Fed, as it was affectionately known, created in 1898. This finally amalgamated all the valley-based trades unions of the South Wales coalfield into one unified union and gave hope to individual miners that they were now better able to combat the employers in their struggles over wages, conditions and safety issues. The clash of capital versus labour was becoming increasingly bitter, even violent, as the employers, through a series of mergers and takeovers, were becoming better organised into smaller numbers of increasingly larger, and therefore more powerful, combines. It was only by being organised themselves that miners had any chance of defending themslves against these onslaughts. As Ammanford-born miner, and future Secretary of State for Wales, Jim Griffiths (1890–1975) remembered in 1969:

"Transplanted from the quiet of the countryside into the turbulent world of industry, the worker needed a defence against the harsh realities of his new life and he found it in the union – the 'Fed'. The Federation was not only a trade union it was an all-embracing institution in the mining community. In the pits it kept daily watch over the conditions of work, protecting the men from the perils of the mine, caring for the maimed and the bereaved, and providing the community with its libraries and brass bands and hospitals and everything which helped to make life bearable and joyous. In the work and in the life of the community the Federation was the servant of all." (Jim Griffiths: Pages from Memory, London 1969, p27)

Miners themselves were overwhelmingly Labour supporters and voters and with the election of a post-war Labour government the Fed were able to realise in 1947 their long-held dream of a nationalised mining industry, an event that occasioned the renaming of the Fed to the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM).

The Communists Come to Town

But for a brief period between the wars, another political party, the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), had an influence in the Amman Valley far beyond its relatively small membership, and during this period of its history Ammanford was one of several places known as 'Little Moscow'. The CPGB was formed in 1920 in the wake of the 1917 Russian Revolution, and a branch was formed in the Amman Valley shortly afterwards, representing the whole of the valley including Ammanford, Betws, Llandybie and the immediate district.The CPGB never became a mass party in Britain, however. Its national membership peaked at about 50,000 during World War Two, when the Soviet Union was one of the Allies, but declined rapidly after that. In the party's history only four members were ever elected to parliament, mostly for short-lived terms, though Willie Gallagher managed to hold West Fife for the Communists from 1935 until 1950. In 1934 the total membership for the whole of Wales was only 3,500. Nevertheless, a highly centralised organisation, with orders often coming directly from Moscow, and harnessing the zeal of a dedicated membership, meant their influence was out of all proportion to their numbers, especially within the mining trade unions which were their stronghold. For many members, an intensity of passion (and obedience) usually associated with religion was transferred effortlessly to political activities instead. (Even as late as 1966, when Amman Valley Grammar School held a mock election during the general election of that year, the Communist candidate came second to Plaid Cymru, beating Labour in the process. The Conservative candidate, in the shape of Neil Hamilton, future MP and disgraced government minister, came last.)

Another institution in Ammanford, the 'White House', was from 1913 to 1922 a centre for working-class adult study, and it provided the nucleus of the local Communist Party, soon to become the largest in Wales outside the Rhondda-Merthyr-Aberdare triangle:

The town of Ammanford had been one of the most important foci of the Communist Party in the South Wales coalfield ever since the foundation of the party. Associated with its activities was the growth of Marxist education in the vicinity. In 1913 Labour College students such as D. R. Owen of Garnant and Jack Griffiths of Cwmtwrch had persuaded George Davidson, a wealthy American anarchist, to buy the 'White House' outside Ammanford as a discussion centre for miners. Out of this grew an unusual local Marxist tradition and it was out of this nucleus of students that the Communist Party was founded. The Communist Party was significantly involved in two major events which broke the calm of the town in the inter-war period. The Anthracite Strike of 1925 which had its origins in the Ammanford No. I Colliery was characterised by unprecedented and violent rioting in and around the town. A decade later similar (although much less violent and dramatic) scenes were re-enacted during the transport dispute of local bus drivers. In this atmosphere, in which Communists played leading roles, many joined the Communist Party. The Ammanford Workingmen's Social Club, founded as a direct result of the 1935 dispute, soon became known as the 'Kremlin'. Its 'Blue Room', where only discussion of politics was allowed, displayed busts of Lenin and Keir Hardie. Two of its founder-members, the Communists Jack Williams and Sammy Morris, both of whom were involved in the 1925 and 1935 disturbances, were killed fighting with the International Brigades at Brunete in the Spanish Civil War. (Source: 'Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War', Hywel Francis, 1984, pages 204 - 205)

Note: fuller histories of the 1925 Anthracite Strike; the 1935 Bus Strike; Ammanford Social Club; Ammanford and the Spanish Civil War; and the White House mentioned above can be found in the 'History' section of this website. Click the 'Back' button on your Browser to return to this page.

But left-wing political parties the world over seem to be prone to furious and frequent splits into warring factions, making them notoriously short-lived as a result. From 1929 onwards, the world's Communist Parties outside the Soviet Bloc experienced splits led initially by Leon Trotsky, one of the architects with Lenin of the Russian Revolution in 1917. After Lenin's death in 1924, Trotsky fell foul of Stalin who'd inherited the leadership, and once Stalin had marginalised Trotsky, he expelled him from Russia in 1929 (and had him assassinated in Mexico City in 1940). Trotsky's own organisation itself soon split into a number of offshoots, as eventually did the CPGB, so that today the far-left parties of Britain, though bewilderingly large in number (and bewilderingly similar in name), are all also tiny in membership. Though it would pain these parties to admit it (and most wouldn't), their influence on politics is minimal to the point of non-existant.

All this time Ammanford's communists remained overwhelmingly 'Stalinist' in their political allegiances; that is, loyal to the Soviet Union and its ever-shifting political line. But our little valley, nestling shyly between the Betws and Black Mountains, was not without a Trotskyist split of its own, as the following obituary written in 1998 of Ammanford-born Olwyn Hughes shows. Olwyn Hughes (1926—1997) was born and lived all his life in Aberlash, Ammanford. His working days were spent in local mines, starting during the war as a boy at Pencae'r Eithin Colliery, Llandybie (opened in 1913, and closed in December 1958). The obituary shows Olwyn Hughes as one of Ammanford's few Trotskyists in an often hostile Communist Party stronghold, a Daniel in the lion's den indeed.

Note: The Ted Grant mentioned in the article was the founder of the British Militant Tendency, once part of the Labour Party until its expulsion, along with the Militant editorial board, in 1983. Militant has itself experienced several splits of its own since then.

A good single-volume history of the struggle for the vote in the UK can be found in: The Vote: How it was Won and How it was Undermined, by campaigning journalist Paul Foot, Penguin, 2005.

Olwyn Hughes: worker, fighter, Marxist

[by Alan Woods]I first met Olwyn in 1971 in a Marxist discussion class we had organised in the small Welsh mining town of Ammanford. But Olwyn's political life went back a lot further, to the period during and just after the War, when he first got active in politics, first in the Young Communist League, and then in the Trotskyist Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP).

.....For a young miner like Olwyn, it must have been difficult not to have been a Communist. Ammanford used to be known as "Little Moscow". And not accidentally. The mining valleys of South Wales had a long history of bitter class war. Memories of the general strike and the inhuman treatment meted out to the miners and their families driven back to work by starvation by the mine owners in cahoots with Winston Churchill were burnt into the consciousness of a whole generation and passed on to the next.

.....The Russian Revolution offered a beacon of hope to these workers who embraced it with that passion so typical of the Welsh. The South Wales miners' union actually affiliated en bloc to the Communist International. Even in the 1970s I remember that there was still a bust of Lenin in the Ammanford workingmen's club where we held our Sunday night meetings, alongside the photographs of young men from the area killed in the Spanish Civil War.Lost Generation

Tragically, the Stalinist degeneration of the Russian Revolution had its effects on the British Communist Party, as all the others. A whole generation of class fighters were cynically duped and deceived. And what fighters they were! In spite of everything, one has to admire the militant spirit and dedication of the Communist workers who sincerely believed that in carrying out the orders of their leaders, they were preparing the revolutionary transformation of society. Olwyn used to speak of one of these, who would be out every evening selling the Daily Worker. A man of small stature, he would stride into the miners' club, plant himself firmly in the middle of the floor clutching his bundle of papers under his arm, and shout out: "Does anybody want to read the truth?"

.....But the real truth was that the Communist Party was no longer a weapon for changing society, but a tool in the hands of the Moscow bureaucracy. This was clearly revealed by the cynical gyrations of the Communist Party line before and during the Second World War. Dudley Edwards, who was a marvellous old comrade, described to me one incident on the eve of the war when Stalin suddenly signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler. Prior to this, the Communist Party line was one of "popular frontism", a class collaborationist policy, the alleged purpose of which was to secure an alliance of the Western "democracies" with Russia against Nazi Germany. Knowing nothing of the change, Dudley was preparing to mount the speakers' rostrum to defend the popular front, when someone tugged him by the sleeve and whispered "Comrade, the Line's been changed!" So he threw his notes away and delivered a speech saying the exact opposite of what he had intended. There were many such cases.

.....The abandonment of the policy of popular frontism and the adoption of an ultra-left policy in the first days of the War did not shake the confidence of the working class Communists, though many middle-class fellow-travellers immediately jumped ship. What really caused dismay in the ranks was the next change of Line. When in the Summer of 1941, Hitler cynically broke his pact with Stalin to attack the Soviet Union, Moscow required a totally different policy. Hitherto, the British Communist Party had been a caricature of Lenin's policy of revolutionary defeatism, demanding, in effect, peace on Hitler's terms. They irresponsibly fomented strikes at the slightest pretext at a time when the British workers were working round the clock for the War effort. Now, at the drop of a hat, the Party called a halt to all strikes and demanded the workers step up productivity for the war.

.....Overnight, without any explanation, the imperialist war became a progressive war against fascism. This was too much for many Communist workers to swallow. How could such a policy be justified? What did it all mean? The only people who gave explanations were the Trotskyists of the Revolutionary Communist Party (RCP). While consistently calling for the defence of the USSR, they advocated a policy of class independence, calling on the Labour Party to break the coalition with the Tories and Liberals and take power on the basis of a socialist policy of nationalising the banks and monopolies under workers' control and management. As a result they were viciously attacked by the Stalinist leaders of the CPGB who issued a scurrilous pamphlet called 'Hitler's Secret Agents', and even called on Herbert Morrison, the Home Minister (and Labour Party member) to illegalise them – which he refused to do.

.....Throughout the War, the Labour Party agreed to an electoral truce with the Tories. They were all in the wartime coalition, so there were hardly any elections. An exception was the by-election in working-class Neath in 1945, when the RCP fielded a candidate in a safe Labour seat. The Stalinists were beside themselves with rage. They did everything possible to disrupt the RCP's campaign, but without success. The RCP made a big impact with its programme and ideas – not least among sections of the Communist Party workers.Self educated

A few miles away from Neath, along a desolate, wind-swept valley, lies the small mining town of Gwaun-cae-Gurwen, popularly known as G-C-G, or "the Waun". Here the RCP established an active branch, mainly of miners who had come over from the Communist Party. The leading spirit was one Johnny Jones, a self-educated man, like many Welsh workers at that time who took the trouble to raise themselves above the terrible conditions of life to conquer for themselves the world of culture and ideas. Johnny used to write marvellous articles for the 'Socialist Appeal' from which you could get a clear idea of the lives, thoughts and aspirations of working people. Still a youth, Olwyn joined this group. He never really left it till the moment of his death.

.....It took some guts to be an active Trotskyist militant in a Communist Party stronghold like that. The Stalinists looked on them as traitors or worse, and on more than one occasion criticism was not limited to verbal exchanges. Olwyn gave me the following example. One of the RCP members (I don't remember the name) was quite a tough man, although quietly spoken. Once, he and Olwyn were chatting over a pint in the local club [Ammanford Social Club, the 'Pick and Shovel'], when a particularly fanatical Stalinist came up behind them and began taunting the alleged "Trotsky-fascists." Olwyn's companion turned round and addressed the provocateur: "Are you talking about me?" The man had scarcely had time to reply in the affirmative, when the fists started to fly. The aggressor ended up on the carpet, whereupon the victor looked challengingly round the room: "Now then. Anyone else got anything to say?" They did not.

.....Of course, my own acquaintance with Olwyn started many years later. Yet he always spoke of that period with the liveliest enthusiasm and affection. There was a reason for that. These were the years that gave him the education and the ideas that would shape the rest of his life. In the bleak days of the capitalist upswing, when the forces of genuine Marxism were isolated for a whole historical period, Olwyn became temporarily cut off from the movement. But unlike others he always kept faith. Not the blind faith of a religious fanatic, but the conscious faith of a working class revolutionary who has absorbed the fundamental ideas and theories of Marxism.

.....When I met up with him in that study group, it was as if the knot of history had been suddenly re-tied. He instantly recognised our ideas as his own. When he met Ted Grant again after many years he commented in amazement: "He's just the same as always". He was really delighted that we had remained firm, defending the ideas of Marxism "just the same as always". He was always a voracious reader and had a very high political level. Whenever we met, he always insisted in discussing theory. The question of the Soviet Union was one of the things that interested him most. Shortly before his death he had just read Ted Grant's new book 'Russia – From Revolution to Counter-Revolution'. He regarded both this and 'Reason in Revolt' as wonderful achievements, and "a real addition to Marxist thought."

.....All his life, Olwyn Hughes remained what he had always been – a working miner. In the last period, he worked in small private pits, and on one occasion he described the kind of conditions that prevailed in them. There was an explosion in a nearby mine, and Olwyn rushed to help with other miners. The first one to enter the mine, at first he could see nothing. Then, as his eyes got used to the dark, he could see a man on the ground, black all over with coal dust. Eventually, the man spoke to him in Welsh: "Olwyn. Don't you know me?" It was a friend of his. What Olwyn did not know was that, beneath the thick layer of coal dust, most of his skin had been blasted away by the explosion. He died shortly afterwards. Later, the mine owner claimed to have found a box of matches in the dead man's pocket. This version was supported by the man from the mines' inspectorate who came to investigate. When I saw Olwyn in the pub, his face was ashen. "Well," he told me, "I was in that mine after the explosion. The heat was so bad, it had melted metal. Yet they say there was a box of matches!"

.....From this single incident you can learn more about Olwyn Hughes and thousands like him than in any book. The unshakeable loyalty to the cause of socialism and the working class he displayed all his life did not come from books, though he loved them too. It came from life itself. From hard experience. From a deep and enduring sense of rebellion against injustice. It is a matter of the most heartfelt regret that I did not manage to see Olwyn before he was taken from us. I had intended to. Now that meeting will never take place. This short tribute must stand in its place. It is the only kind of monument that I know Olwyn would want to have.

January 1998: [From: www.marxist.com][A light-hearted look at the weird and wonderful world of far-left politics can be found in How to form your own political party in the 'History' section of this website.]