THE 1935 AMMANFORD BUS STRIKE

originally published as:

'The Importance of Motor Omnibus Passenger Services

in South West Wales as illustrated by the 1935 Bus Strike'

(Carmarthen Antiquary, Vol 20, 1984, pages 87 – 91)By Russell Davies

The importance of the rail network in the economic development of South West Wales has received some attention from Welsh Historians (see note 1 below). The development of the Welsh rail network created opportunities for specialist agricultural activities, tied to a market economy and extended the relationships between the rural, agricultural and the urban, industrial areas of Wales. A new scale of opportunity was instituted as farmers and townsfolk travelled to settlements on railroad lines to sell farm and products, and to purchase commodities from distant points. However it was the development of the automobile, because of its greater flexibility and availability to private ownership, which revolutionised the pattern of local relations throughout the country. In South Wales in the period 1900-1939, where surplus capital was scarce, the motor car was primarily, though not absolutely, a symbol of social superiority. For this society the force that broke down 'the friction of space' (2) was the development of the motor ominbus passenger service. This short paper attempts to emphasise the importance of omnibus passenger services to the community of South Wales through examining the dislocation caused by the 1935 bus strike.

Motor omnibus passenger services were not unknown in South West Wales before the First World War. In 1904 the Great Western Railway commenced services from nearby villages to Carmarthen station to supplement their rail service (3). In 1909 the M.M.T. Company offered twice daily services between Ammanford and Llandeilo (4) and on the Gower peninsula, John Grove of Port Eynon and the Taylor Brothers of Llangenith began services from their home towns to Swansea (5). On February 10th 1914 the South Wales Transport Company, the company that was to dominate motor omnibus services in South West Wales, was formed (6). However, despite these developments, motor omnibus passenger services before 1914 were sporadic. It was during the inter-war period that an effective network of services was established.

A variety of factors were responsible for the development of motor omnibus passenger services in this period. The war offered men the opportunity to learn to drive and to maintain automobiles, and illustrated the enormous advantages of motor transport over the inflexible rail network. The end of the war brought on to the market large numbers of ex-army chases suitable for conversion into motor buses and large numbers of mass-produced buses from America. But undoubtedly the major factors in the growth of motor omnibus passenger services at the end of the First World War were the rail strike of 1919 and the technical improvements in the manufacture of buses. Of particular importance was the development of the pneumatic tyre and valves of sufficient strength to maintain the necessary tyre pressure. In 1923 it was estimated that a bus fitted with the new tyres could complete a journey in a third of the time that it would take for a bus fitted with solid rubber tyres, and that in much greater comfort and quiet (7).

As a consequence of these factors the number of companies operating bus services grew sharply between 1920 and 1930. In the area of the South Wales Anthracite Coalfield, for example, between 1920 and 1930 over 31 companies were founded (8). This multiplicity of services brought about a profound social change in South West Wales. Town, market-centre, village, hamlet and isolated farm were linked together as they had never previously been. There were profound implications for the commercial and residential roles of these centres. Whilst in personal terms profound occupational and psychological implications were introduced into the lives of individuals (9).

The inevitable result of having forty motor bus operators within the region was the overlapping of services, fare undercutting and races between buses. The situation was worsened by the existing licencing procedure. Licences to motorbus operators were issued, on request, by the local council. The trouble was that only a minority of the operators bothered to apply for licences and that only a few councils, most notably the Swansea Town Council Watch Committee, were conscientious in carrying out their duties (10). The situation was particularly bad in Ammanford, where, in 1925, 16 operators had routes operating through the town. Here drivers frequently raced each other between bus stops and conductors frequently pulled passengers onto moving buses (11). This situation was not improved until the Road Traffic Act of 1930 introduced rigid tests for drivers, buses and operators and appointed Traffic Inspectors to ensure that standards were maintained (12).

The conditions of service for drivers, as may be expected in a situation in which small family businesses controlled small groups of workers, were very bad. Attempts to combine together to form drivers' unions were stubbornly resisted throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. Only the South Wales Transport Company was prepared to accept that it and its workers could be equally well served from dealing with a Union (13). By 1929 almost all its employees were members of the Transport and General Workers Union. The smaller companies were autocratic and dictatorial in their attitude to their employees. And it was the inflexibility and stubbornness of one such company that led to the 1935 bus strike in South West Wales and to the social dislocation of the summer of 1935.

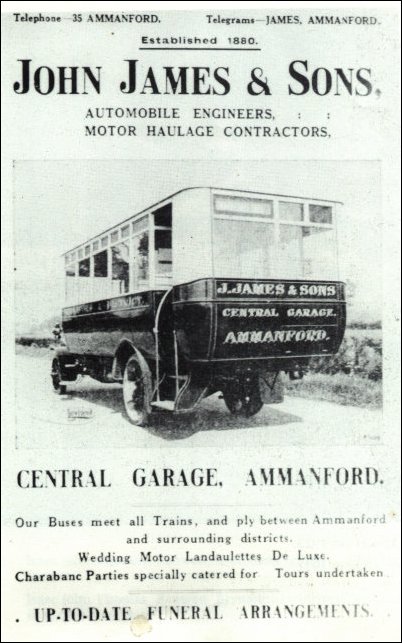

J. James and Sons Ltd of Ammanford had their origins in the 1890s when John James had commenced transporting goods and passengers in the Ammanford area. In 1920 the family commenced motor vehicle passenger services, and through ruthless mergers and takeovers the company by the late 1920s was one of the largest operators in the Amman Valley. The growth of the company meant that the James family and their close relatives were moved from the actual operation of their services into the management of the company and that labour had to be brought into the company from outside the family circle. With this influx of labour came tension. The James family continued to run the company in their traditional parsimonious manner, whilst the workers began to demand adequate wages, working conditions and rights, and the recognition by the company of their union (14).

Throughout the early 1930s attempts had been made for the recognition of the men's union (15), but on August 2nd 1935, in view of the Company's intransigence, the workers, supported by local Trades' Councils decided to strike over a wage claim (16). By the morning of August 3rd, 150 employees of James and Sons and the neighbouring companies 'Rees and Williams', 'West Wales' and 'Bevan and Davies' were out on strike (17). Though the Transport and General Workers Union leadership, plagued at this time by the rebel Rank and File movement refused (18) to support the strike, the men continued on strike.

On Saturday August 10th the James Brothers declared that unless the men returned to work by the following Thursday the company would regard them as having left their employment and they would appoint new men to their places (19). On Friday August 16th the company carried out its threat and appointed six men from Llwynhendy to replace some of the striking men (20). News of this action was communicated rapidly throughout the area and on the night of August 16th a large crowd gathered on Ammanford square with the intention of preventing the resumed services. When the local police attempted to disperse the crowd, the windows of four buses were smashed and the garage of James and Sons was extensively damaged, and a policeman was assaulted (21). Eighteen men were subsequently arrested, 15 of whom were later charged and convicted at the Carmarthenshire Assizes for unlawful assembly.

Though the ostensible cause of this 'forgotten riot' was the decision of the James and Sons to employ 'blackleg' drivers, the confrontation itself was part of the bitterness that had marked relations between local socialists and communists since the disturbances of the Anthracite Strike of 1925 (22). Of the three to four hundred people present on Ammanford square only 18 were subsequently recognised and arrested, and of the 15 actually convicted for public order offences, 11 were members of the local communist party (23). During the hearing at Carmarthen Court on January 5-6th 1936 it becomes clear that much of the antagonism was caused by a feud between local police, in particular a P.C. Prout and local communists (24). Of the 11 communists convicted no less than six had been previously arrested during the Anthracite disturbances of 1925. Three of the arrested later served with the International Brigade in Spain and one of them, Sammy Morris, was killed (25).

At a meeting at Swansea on Saturday, delegates representing the employees of 17 local bus companies, decided to ignore the advice of Ernest Bevin and the T.G.W.U., and to strike from midnight on Sunday if the companies involved in the Ammanford dispute had not agreed to the men's terms. The strike continued until September 9th when the men returned to work with only minimal improvement in their working conditions. Throughout the strike the T.G.W.U. refused to take up the men's case though they received widespread support from local trades' councils and other unions such as the South Wales Miners' Federation (26).

The importance of bus services to the everyday life of the community in South West Wales in the 1930s is clearly illustrated by the disruption caused by the 1935 bus strike. Although a few companies managed to run a skeleton service by employing their white collar workers as drivers and conductors the major part of South West Wales had to manage without buses. From the outbreak of the strike on August and until August 18th, the area affected by the strike was confined to Ammanford and district. The decision of the employees of 17 bus companies to join the four Ammanford companies on strike was to have a profound effect on the local community. The timing of the decision gave the extension of the strike a much sharper impact. After a mass meeting at Swansea on Saturday, August 17th, a decision was taken at 2 a.m (Sunday), that a strike should commence at midnight. Thus the community had no prior warning and was thus unprepared.

Travel to work was, and perhaps is still, regarded as the preserve of professional white collar workers. But in the 1930s a large number of coal miners had to commute to work. In the Gwendraeth valley, for example, 115 of the 543 miners employed at the Blaenhirwaun Colliery had to use the bus service of L. C. W. Motors Ltd to travel to work (27), and of the 1016 colliers employed at the Great Mountain Colliery, Tumble, 215 used motorbus services to get to work. In the Dulais Valley in 1938, 98 men from Merthyr Tydfil travelled 12 miles to work at Onllwyn whilst 110 men travelled the 11 miles from Aberdare. Similar figures can be produced for all of the coal mines of the Anthracite Coalfleld of South Wales in the 1930s (28). It is clear that in the South Wales of the 1930s when several coal mines were closed the motor omnibus was of profound importance because it allowed miners to travel to work and to reside in their home community. The temporary movement of men from their families to lodge near the place of work walking home at the end of the month only once or twice a year that had been such a feature of the early twentieth century was now ending as miners could now commute daily (29).

On Monday August 19th well over half of the total workforce employed in the Anthracite coalfield failed to arrive at work, or experienced considerable difficulties in doing so. Many had to walk or borrow their children's cycles in order to arrive on time. The vast majority had to commence their journey much earlier in the morning and would arrive home much later, a severe inconvenience for miners and their families, as only a few pits were equipped with pit-head baths. Some colliers simply decided to extend their holiday. Attendance at the East Pit, Gwaun Cae Gurwen, and the nearby Steer and Maerdy Collieries were well below average. Miners from Tycroes, Saron and Capel Hendre, who relied on the services of Rees and Williams LTD, James and Sons LTD, and West Wales Motors to get them to work at the Blaenhirwaun, Emlyn No. 2 and Great Mountain collieries were severely inconvenienced by the cessation of services (30). The situation was particularly severe in areas where there was no rail network to compensate for the absence of bus services. In the upper Swansea valley the communities of Abercrave, Ystradgynlais and Pen-y-cae were isolated. Many of the colliers from these communities had to find temporary lodging at their place of employment, whilst several spent over a week without reaching their place of employment (31).

Difficulty in reaching their place of employment was not restricted to miners, workers in all occupational groups shared these difficulties. On the morning of Monday August 19th only six shops in High Street, Swansea, opened on time at nine o'clock. The other shops had to wait for the managers to turn up with the keys before opening, or remain closed. At the Mannesmann Tube Works at Landore great inconvenience was caused to the men completing the midnight shift (32). Girls working at the Tinstamping works in Llanelli, who lived in Bynea and Llwynhendy, had to leave home at 6 a.m. in order to arrive on time for their shift (33). Men who lived in Neath had to walk, or cycle, to their employment at Britton Ferry and Giant's Grave (34). A high percentage of the workforce of Felinfoel had to undertake a foot or bicycle journey through Llanelli in order to reach their work at the Morewood's and Morfa Tinplate works (35).

With the decline in mobility amongst the public, patterns of trade were fundamentally changed. A stallholder at the Neath market stated on August 20th 'today was market day, but the amount of trade done, in comparison with the ordinary market day, was negligible' (36). Women from Penclawdd who normally travelled in to the Neath and Swansea markets in order to sell cockles and other seafoods failed to do so. A local tradesman described High Street, Swansea as being 'practically deserted' on August 26th (37). Trade in Stepney Street, Llanelli was 'at a standstill' according to a local grocer. Another tradesman in Llanelli claimed that trade had dropped by well over 20 per cent (38). On August 27th the Western Mail reported that 'the bus strike has prevented the traditional weekend exodus to Swansea and Neath and has provided very high takings for local businesses'. It was not only the small village shops that benefited from the bus strike, dealers in bicycles, motorcycles and cars, second-hand and new, prospered. One dealer in Swansea claimed that he had sold six times as many bicycles as usual because of the strike (39). Advertisements for cheap bicycles, motorcycles and cars multiplied quickly in the local newspapers during the strike. Many bad no inhibitions about profiting as a result of the strike. C. M. Day LTD of Swansea offered 'Special Strike Bargains' in used cars (40). Whilst Dan Morgan, also of Swansea, ran the following advertisement: 'Bus and Tram Strike! Don't walk to work ride a Raleigh bicycle, it will never let you down. Own your own transport for less than 2s 4d a week' (41).

Motor omnibus passenger services were of profound importance for the establishment and growth of leisure activities, in particular group leisure activities such as rugby and football clubs, choirs etc. Consequently the effect of the strike on these activities was dramatic. By August 9th, over 500 people who had booked excursions to Aberystwyth with the four Ammanford companies then on strike, had their money refunded because of cancellations (42). The Landore Poor Children's Outing Fund organisers had to twice cancel the proposed outing to Port Eynon, before cancelling it altogether on August 30th. A trip to Caswell organised for the 69 children at the Cottage Homes in Swansea also had to be cancelled (43). On September 9th the Swansea Education Committee received an intimation from the South Wales Transport Welfare Committee that, owing to the strike, 800 Swansea schoolchildren would be given a tea instead of an outing, as was usual (44). The disappointment of local children increased as first the Sunday School trip, then the school trip, and then the Institute's trip were cancelled.

The effect of the cancellation of trips and excursions was particularly damaging to the hoteliers and cafe owners of the Gower peninsula. The manageress of the Langland Bay Hotel complained that the lack of 'charabanc' trips and cancellation of bookings had almost halved their normal takings. Also suffering were the owners of small beach cafes, who, after a poor June owing to the bad weather, were now, in blistering sunshine conducting even less trade. A correspondent of the South Wales Evening Post writing of the Gower beaches, declared that 'those who reached them were able to find the secluded beach corners that were regarded as a prerogative of the pre-bus era' (45).

Virtually every section of the community was adversely affected by the bus strike. Several angry letters were written to the local newspapers complaining that the old aged had to walk. Much bitter feelings were aroused by people having to walk up Town Hill in Swansea (46). The magistrates at the Gower Petty Sessions on August 16th, were hindered by late arrivals owing to the bus strike (47). Disruption was caused to the Outpatients' Department at Swansea Hospital: On August 22nd the Matron in charge complained that 'I have a staff of eight masseurs in the outpatients department and they are all idle' (48). Attendance at the Llandeilo and Swansea 'Shows' was markedly down on previous years. A rally which was to be held on September 5th at Brunswick Methodist Church, Swansea, to welcome new ministers to the circuit, had to be cancelled because of the bus strike (49).

Perhaps the episode which best illustrates the importance of bus services to the local community is the case of two Ynysforgan cricket enthusiasts. Both were aged 82 and were keen supporters of Glamorgan [County Cricket Club]. They walked to Neath, a journey of 10 miles to see the fixture against Essex. Glamorgan lost by an innings and 33 runs. Their return journey reflects much on the importance of bus services to the local community (50).

REFERENCES 1 Howell, D., 'The Impact of Railways on Agricultural Development in Nineteenth-Century Wales', Welsh History Review, Vol. 7, No. 1 (1974) pp.40-62. 2 Moline, T., 'Mobility and the Small Town 1900-1930', Department of Geography Research Paper No. 132, University of Chicago, (1971), p. 4-5. 3 Edwards, J. A., 'Transport and Communications' in Balchin, W G W, Swansea and its Region, Swansea (1971), P274. 4 Thomas, Bryn, Days of Old Llandybie Notes and Memories, Carmarthen (1975) p. 69. 5 Brewster, D., Motor Buses in Wales, 1898-1932. London (1976) p.3. 6 P. S. V. Circle and the Omnibus Society Fleet History PG4, The South Wales Transport Company (1976) p.3. 7 Motor Transport (1976) p.3. 8 Eclipse (Pontardawe); John Rees (Ystalyfera); Lark Bus Services (Trebanos); W. L. Davies (Clydach); Bassett's (Gorseinon); Morgan's Services (Ammanford); Morley Services (Gorslas); Bishopston and Murton Services (Bishopton); A.Thomas and Sons (Tirydail); All Blue Company (Neath); Swan Bus Services, F. Taylor and Sons (Cross Hands); Eclipse (Clydach); F. Roderick (Dunvant Ltd. (Skewen); R. Jenkins and Sons (Bonymaen); J. M. Bacus aand Co. Ltd. (Burry Port); Willmore Services (Neath), Treharne Bros. (Porthenry); John Bros. (Grovesend); Osboume Services (Neath); L. C. Williams (Llandeilo); Davies Bros. (Loughor); Blue Bird Service, (Neath); Windom and Richmond Services; Bevan and Davies (Pantyffynon); Rees and Williams (Tycroes); South Wales Commercial Motors (Cardiff) begins to operate services in the area in 1928). 9 For a fuller discussion on these themes see Moline, T., ibid, pp. 122-164. 19 The Eclipse Saloon Service of Clydach, Roderick Services of Dunvant, Bluebird Bus Services of Skewen and R. Jenkins and Sons of Bonymaen were unlicensed throughout the 1920s. See Fleet History, p. 94, p. 6 11 Information supplied by the late Mr D. Davies, 28 Norton Road, Penygroes, Dyfed, a former driver with James and Son, Ammanford. 12 For the effects of the Road Traffic Act of 1930 see Royal Commission of Transport Final Report, Cmd. 3751, 1930, and Hibbs, John, The History of British Bar Services, London (1968), p. 105. 13 Motor Transport, August, 1926. 14 Daniel, Bryn, 'The Forgotten Riot', an unpublished typescript in the South Wales Miners' Library, Bryn Daniels Papers, Box 1. 15 News Chronihcle, July 29th, 1935. 16 Western Mail, Daily Herald, Amman Valley Chronicle, August 2nd, 1935. 17 Ibid., August 6, 1935. 18 See Bullock, Alan, The Life and Times of Ernest Bevin, vol 1 'Trade Union Leader 1881-1940', London (1960) pp. 550-552. 19 Amman Valley Chronicle, August 15th. 20 Daniel, Bryn, ibid., Much cf what follows is based on this eyewitness' recollection of events. 21 Amman Valley Chronicle, August 22nd, 1935. 22 Francis, H., 'The Anthracite Strike and the Disturbances of 1925', Llafur, Vol.1, No. 2, 1975. 23 Daniel, Bryn, Ibid. 24 Carmarthen Journal, January 1oth, 1936. 25 See also Daniel Bryn, ibid.; Arnot, R.P. The South Wales Miners 1914-1926, London, (1975), p 355. 26 Western Mail, August 17th, 1935. 27 L. C. W. Timetable, 1939. 28 For an indication of the importance of commuting to miners see Howell, Emrys Jones 'Movements of mining population in the Anthracite mining area of South Wales, 1861 to the present day', unpublished MSc University of Wales (Swansea) 1938 and 'Movement of Miners in the South Wales Coalfield', Geographical Journal, Vol. 93, No. 3, Sept 1939 pp. 223-237. And also Griffiths, I. L., 'Daily Movement to work of Anthracite Miners in South Wales' in Tijdschrift voor Economischeen Sociale Geogrofi, Vol 53 (1962), pp. 184-190. 29 See for example Williams, D. J., Yn Chwech ar Ugain Oed, Llandysul (1959), pp. 145-194. 30 South Wales Evening Post, August 19th, 1935. 31 32 33 Ibid., August 26th. 34 Neath Guardian, August 23rd, 1935. 35 Llanelly Mercury, August 29th, 1933. 36 South Wales Evening Post, August 21st 37 Ibid., August 24th, 25th, 27th. 38 Llanelly and County Guardian, August 29th; South Wales Evening Post, August 26th. 39 Western Mail August 27th and 30th, 1935. 40 South Wales Voice, September 7th, 1935. 41 South Wales Evening Post, August 21st, 1935. 42 Llanelly and County Guardian, August 22nd, 1935. 43 South Wales Evening Post, August 27th, September 3rd, 7th, 1935. 44 Daily Herald, September 10th, 1935 45 South Wales Evening Post, August 29th, September 4th, 1935. 46 Western Mail, August 20th; South Wales Evening Post, August 22nd, Amman Valley Chronicle, August 29th, 1935. 47 South Wales Evening Post, August 23rd, 1935. 48 Daily Herald, August 23rd, 1935. 49 Amman Valley Chronicle, August 22nd, South Wales Evening Post, September 3rd and 4th, 1935. 50 Western Mail, August 27th, 1935. Source: originally published as:

'The Importance of Motor Omnibus Passenger Services in South West Wales as Illustrated by the 1935 Bus Strike', (Carmarthen Antiquary, Vol 20, 1984, pages 87 – 91). Reprinted with the kind permission of the author.