AMMANFORD AND THE

SPANISH CIVIL WAR

AMMANFORD MINERS DIE IN SPAIN"And it came to pass when David returned from the slaughter of the Philistines, the women came out of all the cities of Israel, singing and dancing, to meet King Saul, with tambourines, with songs of joy, and with instruments of music. And the women sang to one another as they made merry. "Saul has slain his thousands And David his ten thousands" And Saul was very angry, and this saying displeased him; he said "They have ascribed to David ten thousands, and to me they have ascribed but thousands ..." And Saul eyed David from that day on." (1 Samuel, Chapter 18, verses 6 - 9)

1. INTRODUCTION

Three Ammanford men were so eager to become freedom fighters in the Spanish Civil War that they attempted to stow away in a Spanish ship sailing from Cardiff docks.

Bachelors Sammy Morris, Jack Williams and Will Davies had traveled to Cardiff in 1936 to attend a meeting organized by the Welsh Communist Party when they decided to support the heroic struggle of the Spanish Republic against Fascism. Addressing the meeting and appealing for support were two Spanish seamen concerned about their country's plight, with their ship docked in Cardiff.

After the meeting attended by a busload of communists and supporters from the Ammanford area, Sammy Morris, Jack Williams and Will Davies went mysteriously missing, delaying the bus from returning to their home town. It later transpired that the three men had attempted to stow away in the Spanish ship, hell bent on supporting the Spanish Republic's cause. Somehow or other the police had been tipped off and the three were arrested and released after questioning. A week later they all met at Ammanford Social club (the Pick and Shovel) when the Spanish situation and the possibility of volunteering arose again

General Francisco Franco, head of the Fascist armed forces during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and "il Caudillo", dictator of Spain from 1939 to 1975. At the meeting were Sammy Morris and Will Davies, who were in their late 20s. A week later their friends and family heard that they had left for Spain. They had joined the International Brigade, fighting for the democratically elected Popular Front government against Franco's Fascists. General Francisco Franco and his supporters had refused to accept election results which had returned a Republican government, and rose up in a civil war that was to engulf Spain for three years between 1936 and 1939, and result in as much as one million dead. In 1934 Spain got a taste of what was to come from General Franco when troops under his command brutally suppressed a rebellion of Spanish miners in the Asturias region of northern Spain. In just two weeks of one-sided warfare 3,000 miners were killed. Franco's tactics owed nothing to subtlety: captured miners were used as human shields; food queues were bombed from the air; and the imprisonment and torture of 35,000 captured miners and their families continued well into 1935. No wonder these Ammanford miners so closely identified with the Spanish Republic when Civil War broke out in 1936.

The next the people of Ammanford heard was that Sammy Morris and Jack Williams had been killed in action in July 1937 during the battle of Brunete in defence of Madrid. No one knew how they had been killed, only that they had died in action. The third member, Will Davies, known to his friends as Will Castell Nedd (Will Neath), returned safely. Portraits of Sammy Morris and Jack Williams hang in Ammanford Social Club to this day in memorial of their sacrifice. Here is a profile of the International Brigades' Welsh contingent, which describes Ammanford's five volunteers with almost uncanny accuracy:

The 'typical' Welsh volunteer was invariably a miner who was unemployed as a result of his trade union activities. His first and most telling political and trade union experience would have been the 1926 General Strike and lock-out. He would have played a part in many extra-parliamentary actions from 1926 onwards, including hunger marches, street demonstrations, stay-down strikes and disturbances for which he could have been fined or even imprisoned. An activist in the SWMF (South Wales Miners Federation) from an early age, and then the CPGB (Communist Party of Great Britain), he would have come from a mining family, often large and poverty stricken. The contingent from the mining valleys of South Wales was by far the largest regional occupational grouping within the British battalion. Indeed, there were more from the South Wales Coalfield than from all the other British coalfields combined. (Source: http://www.agor.org.uk/cwm/learning_paths/spanish_1.asp)

Inferior military capacity led to the gradual defeat of the Republicans by 1939, though political infighting (including actual fighting) between the various factions in the Popular Front coalition played its part. Franco's insurgents (Nationalists), who were supported by Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, seized power in the south and northwest of Spain, but were initially suppressed in areas such as Madrid and Barcelona by the workers' militias. The Loyalists (Republicans) in contrast received only limited international support from the USSR, along with the International Brigades made up of poorly equipped volunteers from many parts of the world.

The Popular Front armies of the Spanish government collapsed due to the lack of support from other democratic governments, including the Tory British government, even though Franco's Fascists received considerable military aid from Hitler's Nazis and Mussolini's Fascists. This included German bombing of Spanish towns, most notably the saturation bombing of Guernica in 1937. Sadly, the Popular Front had no similar support, and the French government even prevented volunteers from travelling through France to Spain, deporting them to their countries of origin if caught. From April 1937 the major European powers of the day signed a Non-Intervention Agreement, which included making recruitment for Spain illegal. In order to ensure conformity to this 'Agreement' ships of the participating navies (Britain, France, Germany and Italy) were authorised to intercept and examine any suspicious vessel that came into their zone. Given that Germany and Italy were not only supplying Franco with arms but also bombing Republican towns, it was hardly 'non-intervention' in any meaningful sense. Many merchant boat-owners, however, ran the French and British naval blockades to smuggle much needed food, arms, and volunteers into Spain (see 'Potato' Jones below), and a lucrative business it proved to be for them.

Britain and the USA refused to aid the Spanish Republic, even denying that Germany and Italy were bombing Republican targets. But their denial was as hypocritical as it was untrue:

American and British business interests were to make a great contribution to the final Nationalist victory, either through active assistance, such as that given by the oil magnate, Deterding, or through boycotting the Republic, disrupting its trade with legal action and delaying credits in the banking system. (The Midland Bank was alleged to have been the most active in this way.)

.....Spanish industry had been dominated by foreign capital since its retarded start in the mid-nineteenth century. The railways and basic services such as electricity, engineering and mining all depended on heavy foreign investment. American ITT owned the Spanish telephone system and Ford and General Motors had little competition in the motor industry. British companies owned the greatest share of Spanish business with nearly 20 per cent of all foreign capital investment. The United Kingdom was also the largest importer of Spanish goods, including over half of her iron ore. (The Spanish Civil War, Antony Beevor, Cassell Paperback, 1999, page 114)A democratic, Republican Spain might threaten these commercial interests, and a mere technicality like democracy is of little concern to national governments when the interests of their ruling class are challenged.

But the British government wasn't even neutral during the Spanish Civil War – there is now incontrovertible proof of British involvement in actually starting the Franco-led uprising on July 18th 1936:

New evidence has emerged showing that a Briton who helped fly General Franco to launch the uprising that became the Spanish Civil War was an MI6 agent. The evidence indicates that Britain's intelligence services played a covert vital role in helping the dictator to power.

.....Recently de-classified documents on Spain at the Public Record Office, Kew, show that Major Hugh Pollard, who travelled on the plane that brought Franco to take command of the rebel Army of Africa, was an experienced Intelligence operative, who later, in 1940, was stationed in Madrid working for M16.

.....Franco was in internal exile commanding the Canary Islands garrison when the right-wing military coup against the Spanish republic was launched in July 1936 (see 'Flying for Franco', by Paul Preston, BBC History Magazine July 2001). He was ferried to take command of the military revolt in Spanish Morocco by a British plane and pilot organised by Luis Bolín, a Spanish journalist in London who later became Franco's Press Chief. Bolín had contacted Douglas Jerrold, editor of a right-wing Catholic journal, The English Review, and over lunch at Simpson's in the Strand they decided to charter a De Havilland Dragon Rapide aircraft and a pilot, Captain Cecil Bebb, from Olley Air Services at Croydon aerodrome, London's air terminal.

.....Jerrold brought a fellow Catholic, Major Hugh Pollard, into the plot and arranged for him to travel on the plane to Spain, along with Pollard's daughter, Diana, and another young woman, Dorothy Watson, as 'cover'. In his published account of the plot, Bolín portrays Pollard as a bluff huntin' and fishin' officer type who spoke no Spanish, but the PRO documents show that he was a Spanish-speaking, experienced military intelligence officer and firearms expert who had served in wars and revolutions in Ireland, Mexico and Morocco, ostensibly as a journalist, but almost certainly as a British secret service agent. Pollard, not Bolín, took charge of the successful operation to spirit Franco from the Canaries to North Africa.

.....The new evidence suggests that Pollard's Intelligence superiors knew of the true purpose behind the flight from Croydon to the Canaries, and that Special Branch at Croydon, who monitored all international flights, allowed Pollard to proceed with an operation that ultimately helped to overthrow a democratically elected Government, and replace it with Franco's dictatorship, which lasted from his Civil War victory in April 1939 until his death in November 1975.(BBC History Magazine, April 2002; article by Michael Alpert, Emeritus Professor of Spanish history at Westminster University.)

Unfortunately, Fascism won the day, and Ammanford lost two fine young men fighting for freedom. Franco went on to rule as dictator of Spain from 1939 until his death in 1975. History has been kinder to Spain since Franco's death, however, and his dictatorship didn't survive the dictator. With the eventual return to democracy, many statues and memorials erected to 'Il Caudillo' in his lifetime were pulled down, and some buildings and town squares that once bore his name have been renamed. Unfortunately Spain did not got rid of all the symbols, street names and monuments from the dictatorship era. When Franco died he said "I left everything set, very well set indeed". Spain today, though democratic, is not the Republic that the war was fought over; like Britain, it is a constitutional monarchy. Nobody has apologised for anything and nobody in the Franco side has been charged for anything that happened during the civil war or during the forty years of repression and dictatorship afterwards, a legacy Spain was late in coming to terms with. After Franco died in 1975 an amnesty law in 1977 ensured that no one could be held to account for the crimes committed during El Caudillo's regime. But the mood was slowly changing. In 2007, Spain's prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero brought in a law to offer justice to victims of Franco. The Law of Historical Memory—although tame compared with South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission—makes it easier to find and dig up graves, and has ordered Francoist plaques and statues to be withdrawn from public buildings. Just as importantly, the law also opened up archives from the period. (Click on A painful past uncovered for a fuller story in the Guardian on recent delevelopments in reconciliation.)

The most widely quoted figure for executions and political killings by the conquerors between 1939 and 1943 is nearly 200,000 Republicans, and Spanish concentration camps of this period have been compared to those of Hitler and Stalin (see The Spanish Civil War, Antony Beevor, Cassell Paperback, 1999, page 267).

But the Spanish Civil War, drenched in blood though it was, proved to be merely a dress rehearsal for what was to come, when the rest of the world was plunged into the horrors of World War Two. The outbreak of hostilities in 1936 was the prelude to the most momentous events in the whole history of Europe. The fate and direction of world history for the next ten years were decided on the battlefields of Spain, and the following decade of carnage and destruction on a world scale is now an historical witness to this claim.

Sincere people from all ranks of society volunteered to fight alongside the Spanish people in their struggle to save their People's Government and their country from Fascism. The ever-growing numbers of volunteers led to the formation of the International Brigades to fight alongside the loyal Spanish workers in struggle. For Britain and her politicians however this event was nothing but an internal struggle for power. To Adolf Hitler, Mussolini, General Franco and the rest of the fascist states of Europe, it was much, much more – a testing ground for their future atrocious attacks on the whole of Europe.

Many ordinary people, too, were ahead of their time in understanding the political implications of Spain; their vision looked further than their blindfolded political leaders. They saw all too clearly that this event not only represented an attack upon the freedom and democratic rights of a government elected by the Spanish people, but was an affront to democracy everywhere. Some gave their lives on the battlefields of Spain. Others returned home only to partake again in the anti-fascist war that was to overwhelm the whole of Europe. A war which, it had been predicted, would be inevitable with the defeat of democracy in Spain. The ordinary people of the Amman Valley gave their support to the Spanish Republican cause with protest meetings calling for action from the Tory Government, and the supplying of food and financial aid to the Spanish people. Where governments turned a blind eye to the plight of democratic Spain, the Republic received magnificent support from British people who raised money and supplies for their cause.

The greatest sacrifice of all was made by five Amman Valley men who volunteered to join the International Brigades and gave their service in action on the battlefields of Spain. These brave men, over sixty years after the Civil War, surely deserve our respect and remembrance for their service to humanity. These five – Samuel Morris, Jack Williams, Will John Davies (Will Castell Nedd), Dai Jones and Will Rees, Garnant, all answered the call in defence of democracy.

Samuel Morris and Jack Williams sacrificed their lives in the cause (a small plaque to their memory can be seen at the entrance to the Council Chamber in Ammanford Town Hall). Dai Jones was wounded and Will John Davies and Will Rees (Will Garnant), returned home. Will John Davies (Will Castell Nedd) escaped back to the Amman Valley surviving, so legend has it, by robbing banks as he made his way through France to safety.

About 2,100 people volunteered for the International Brigades from the British Isles, of whom 526 died, and about 1,200 were seriously injured. That's a quarter of all combatants killed and over half seriously injured, very high percentages indeed. 174 people volunteered from Wales of whom 33 never returned and lie buried in the Spanish soil they died to defend. Estimates for the total death toll in the war range from 350,000 to 1.2 million, depending on which historian you read. Unfortunately, politics plays as much a part in estimating fatalities as it did during the war itself. Right-leaning historians tend to play down the number who died; their left counterparts, in contrast, prefer larger numbers.

Recent histories of the Spanish Civil War and the Soviet Union have tended towards a revisionist interpretation of events, as older, left-sympathising historians are gradually being replaced by a younger, more conservative breed. Some reasons for this are genuine enough, based on a flood of previously unseen documents from Spanish, Russian and German archives, released since the death of Franco and the ending of the Cold War. But politics still bedevils history, an eerie half-world where all historians claim to be impartial and none is, and nowhere more so than Spain which continues to be an emotional issue even after so many decades.

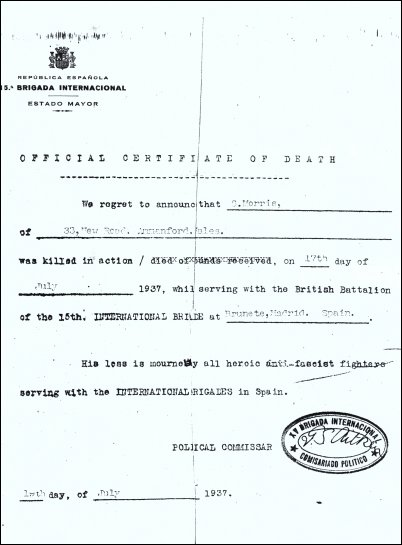

Death certificate of Ammanford's Sammy Morris, killed in action in Spain. The text reads: "We regret to announce that S. Morris was killed in action on 17th day of July 1937, while serving with the British Battalion of the 15th International Brigade at Brunete, Madrid, Spain. His loss is mourned by all heroic anti-fascist fighters serving with the International Brigades in Spain." Issued by the Political Commissar of the 15th International Brigade, G. S. Aitken. (Kindly provided by David Morris of Ammanford, nephew of Sammy Morris.). G. S. Aitken was the father of London Guardian journalist Ian Aitkin. Postscript: Welsh mercenary pilot Cecil Bebb

In this story about Welsh miners who fought and were killed in defence of democracy in Spain, it's a cruel coincidence that it was another Welshman whose actions enabled the Spanish Civil War to start in the first place. When a Popular Front government was democratically elected on 16th February 1936, one of its first acts, on the 22nd February, was to relieve the Fascist's most dangerous General, Francisco Franco, of his command and banish him to the Canary Islands (definitely not a tourist spot in 1936). The Fascist Party headquarters in Madrid were then closed on 27th February, and the Fascist Party banned altogether on 14th March. On July 18th, however, Franco was secretly flown to Morocco from where he took command of the Army of Africa, Spain's only experienced professional division. Once Franco arrived, another airlift, the first such operation in history, then saw much of his army transferred across the Straits of Gibraltar to the mainland, courtesy of aircraft and pilots sent to Franco's aid by Hitler and Mussolini. The Spanish Civil War had begun.The man who piloted the English Dragon Rapide aeroplane that brought Franco from the Canary Islands was a Welsh mercenary, Captain Cecil Bebb, without whom the Spanish Civil War might never have got off the ground. Given Wales's proud record in fighting fascism it's somewhat ironic that the pilot who flew Franco from the Canary Islands to launch his invasion from Morocco was from Church Village near Pontypridd and who went to school at Pontypridd Grammar School. He was a pilot in the Royal Air Force during World War One, becoming a freelance commercial pilot afterwards. Bebb had flown from Croydon airport in July 1936 to pick up Franco in the Canaries, where he had been exiled by the elected Republican government, and then fly him to Morocco.

Bebb was twice decorated by Franco in recognition of his services: in 1938, with the Spanish Civil War drawing towards its close, Bebb was presented by Franco with the Grand Cross of the Imperial Order of Red Arrows and other Spanish decorations. The aircraft that carried Franco to Tetuán in Morocco, DM89 Dragon Rapide (G-ACYR), was later presented to him after World War II and is now preserved in the Museo del Aire near Madrid. In 1970 Bebb was again invited to meet Franco, who conferred on him the Order of Merit and the White Cross in Madrid.

2. AMMANFORD'S FIVE VOLUNTEERS

In communities throughout Wales those who went to fight in the Spanish Civil War are remembered, not because their names are in any history books, but because their stories have been passed on through families, friends and comrades.

Ammanford has some of the best stories of all. They are full of storylines and characters that any film scriptwriter would be proud of.

Sammy Morris is a perfect example of the Welsh Communist miner in the inter-war years. Born in 1908, he joined the Communist Party in 1925 when he was put in jail for his part in the four-month-long strike in the Anthracite District of that year. He became chair of his miners' lodge and was active in his support of local, national and international industrial and anti-fascist struggles. And this at a time when, as Billy Griffiths (an International Brigader from the Rhondda) put it: “Politics was no longer a game ... Slogans became clothed in flesh and blood.” Sammy volunteered to go to Spain, refused to return home when wounded, and later died at Brunete. His letters below sum up him and many of his comrades of the time, a mix of fierce politics and thoughtful kindness: “Share the wealth; share the land; share the rhubarb; share the tent.”

Another character that no writer could invent was W. J. Davies, better known locally as Wil Castell Nedd (Wil Neath). A miner from a strong socialist family, he left the mines when he realised he could make money in the summer from winning sprint races at fairs and carnivals across the South West of England and in the winter from playing rugby, firstly with back-handers and “expenses” as an amateur at Llanelli and later as a Rugby League professional in Yorkshire. He had been a professional for Batley Rugby League Club from 1928 and at the time of volunteering he was in the process of negotiating a transfer to Huddersfield. Sometime in late November 1936 he received a letter from his Ammanford friend, Sam Morris, suggesting that they should both go to Spain. Davies immediately caught the midnight train from Batley and was in Pantyffynnon, Ammanford, by 7.30am. In his own words:

"After having breakfast with my parents I went to Sam's, we understand each other. At the weekend we went to Cardiff ... We were directed to Victoria Station to get a return to Paris .. There were about a dozen Britions there ... We stayed at Perpignan a night. The French border police let us through without even looking at our passports. Then on to Barcelona where we met a lot of Canadians in barracks there ... Two days later we were in Valenacia ... Albacete on day later ... The following day there was some organising for the International Brigades with the British Battalion taking some shape." (Quoted in Miners Against Fascism, Hywell Francis, 1984, page 164.)

The return ticket to Paris was to lead border police to believe they were tourists who intended to return to Britain.

If Hollywood made the film, it would focus on the relationship between Sammy and Wil, with an opening scene either of them sitting together at their Parcyrhun classroom or swimming together at Junction Pool. It could show them earning pocket money by acting as guides to Swansea poachers. It could show them as teenagers in the mines, and later stealing coal to give to the poor during the strikes of 1925 and 1926. It could show them packing up their holiday camp at Caswell Bay on the Gower to come back and join the bus strike picket of 1935. It could show them in the Pick And Shovel club which they helped set up. It could show a letter going from Yorkshire to Ammanford (or the other way) suggesting they go out to Spain. It could show them fighting side-by-side at Jarama and Brunete. And it could show Wil, having seen his childhood friend shot dead on the battlefield by Franco's fascists, returning home, over mountains and seas, swimming rivers and surviving on berries, all of it true. Ill for over a year after his return, he never played rugby again, although he did recover enough to organise rent strikes in London in the 1950s and to be active in the Vietnam demos in the 1960s. Another version of the story has Wil falling ill while still in Spain and coming home before Brunete, but that doesn't make as good an ending does it?

Wil and Sam are the two volunteers whose legends have survived (and grown) most locally, but that shouldn't take away from the others who went to Spain. All five who went out were long-time friends and comrades, but one, Jack Williams, perhaps made the ultimate sacrifice for his best friend Dai Jones. Dai was the only married volunteer. He left for Spain, giving a goodnight kiss to his five-year-old son and without telling his wife. When he was sent home with a hand injury, he planned to go back once he had recovered, but Jack Williams, his best friend and a bachelor, said that he would go instead. Jack, a carpenter by trade and a skilled craftsman, was killed at Brunete within days of his friend Sam Morris. Wil Rees, an unemployed miner from Garnant who had gone out with Dai Jones, returned some time later with an eye injury. He is the volunteer about whom there is least information, but ironically he probably fought in Spain longer than any of the others. He later moved to the Midlands to work in the car industry.

(From a leaflet by Phil Broadhurst, written for an exhibition on Wales and the Spanish Civil War shown in Ammanford library throughout July 2007.)

3. LETTERS HOME

Sammy Morris made the ultimate sacrifice when his young life was brutally cut short in 1937, but even his non-combatant brother Theo was to feel the wrath of his own ruling class back in Ammanford. In the 1930s, most coal mines in the Amman Valley and district were owned by one company, the Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries Ltd (AAC). The AAC's agent in the Amman Valley region, and a major shareholder, was one Mr. David Jeffreys, responsible for overseeing the running of their mines in the area. He was also a deacon of Bethany Calvinist Methodist church in Ammanford, and thus a man of considerable influence in the political and economic life of the community. (There is a brief history of Bethany in the 'Churches and Chapels' section of this website or click HERE.). Jeffreys lived in style in Wansbeck House, Dyffryn, one of Ammanford's grand homes.

At this time in Ammanford's history the power of the chapels was formidable; almost all colliery managers, under-managers, officials and other management staff attended local chapels, often sitting on the governing bodies as deacons. Whenever a man wanted a job for himself or his son, he would quite literally have to go cap in hand to one of these men after a Sunday service, and hope his deference would gain him a desperately needed job. Cross one of these men, however, and life could be made very difficult indeed. Because he was the brother of Sammy Morris, Theo Morris was unable to find employment anywhere in the Amman Valley for ten years when Jeffreys put his name on a blacklist, using all his influence to ensure no local colliery manager engaged him. Sammy Morris was a Communist Party member, a party with an avowedly atheist philosophy, which didn't exactly endear him to local chapel dignitaries like Jeffreys. Theo, in contrast, was himself a member of the very same Bethany chapel as Jeffreys, a fact that failed to impress Jeffreys or soften his heart towards him, and he was punished with unemployment for ten years through no fault of his own. While he was in Spain Sam Morris wrote numerous letters home to his mother in Ammanford and in some he expresses concern about his brother Theo's jobless situation:

"I would like to know how things are with you financially, is Theo still getting the dole, how much is he getting, has he claimed benefit for you, if not, why not?" (Sam Morris, letter to his mother, 8th June 1937, no address given.)

"We have been travelling for many days now in Spain, there is continual sunshine here, the weather being splendid. We find the Spanish people very sociable, there is nothing too much for them to do for us, most of the people work on the land which is very flat and fruitful. The Spanish people have for many years been in bondage to the landlord and the priest, and since these have been driven out, the people have entered into a new world, a world they will defend from Fascism, to the last man woman and child ... I hope Theo has had his job back, he must go up the lodge [ie union] secretary and remind him of the promise he made to me and tell him I will write to him as soon as I can, Sam. ... P.S. I almost forgot – about Xmas, here's wishing you and Theo Merry Xmas and very prosperous New Year." (Sam Morris, undated letter to his mother from Soccorro Rojo International, Chambre 1124, Albacete, Spain. The postscript suggests that the letter was written around Christmas 1936)

Other letters see Sam Morris express his political beliefs in no uncertain terms, and describe the Spanish situation in a way that only one who was there could have known:

"It is Sunday today but I fail to see much difference on Sunday than any other day of the week. This fact is easily explained in that the Roman Catholic priests used their power before the Revolution to keep the people in ignorance and as the biggest landlords in Spain they were in a position to tax the people even to the point of poverty and semi-starvation, but they continued to pray and pose as the saviour and guardian of the people. But when the people successfully voted a Popular Front government the priests knew that this power to exploit the people could be taken from them, so they came out in their true colours and joined the Fascists in their rebellion against the government. They used the church buildings for machine gun nests and fired on the people, men women and children. The churches they also used for ammunition dumps and turned them into the uses of war, as is now well known. They are now helped in their murderous work by German and Italian Fascism who rain bombs from the skies at night on sleeping children and their mothers and shatter them to pieces. I note in your last letter you state that the people at Ammanford pray for Will and myself, I earnestly hope you will also remember these innocent people who are massacred at the hands of International Fascism. I would respectfully remind Theo that prayer without deeds is of no avail, you must convince everybody of the justice of our cause, do everything in your power to bring about the unity of every peace loving individual into any campaigning that will help the Spanish people's victory." (Sam Morris, letter to his mother dated 28th February 1937, c/o Soccorro Rojo, Plaza Alcongona 161, Albacete, Spain. The Will referred to in the letter was either fellow volunteer Will Davies (Will 'Garnant') or Will John Davies (Will 'Castell Nedd', who both returned to Ammanford.)

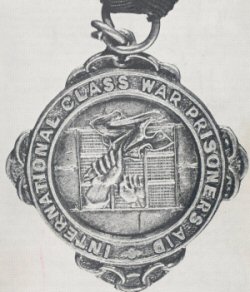

Sammy Morris was no stranger to the mine owners when he went to Spain in 1936, however. During the 1925 strike in the Anthracite District of west Wales, with Ammanford as its storm centre, he had been one of 58 striking miners imprisoned in retribution for four months of pickets and disturbances the whole length of the Amman Valley. The strike started at Ammanford No 1 Colliery in April 1925 and during the next four months Ammanford was the epicentre for riots and mass demonstrations whose shock waves were felt all over the district. On one day alone, July 30th 1925, there were riotous disturbances simultaneously at Ammanford square; Ammanford No 2 colliery, where there was a police baton charge; at Betws; and also at Wernos, Pantyffynnon and Llandybie collieries. And the major battle was yet to come, the so-called 'Battle of Ammanford' which occurred on August 4th. In total 198 miners were arrested with 58 being jailed for periods of up to one year. Months after the strike had ended there was still huge involvement as the prisoners were released, and on April 3rd 1926 a mass rally in the Ivorites Hall in Ammanford drew charabancs from all over the valley. Each prisoner on his release was awarded a medal and a scroll by the International Class War Prisoners Aid Association (ICWPA). (For a fuller account of the Anthracite Strike click HERE.)

Sam Morris's International Class War Prisoners' Association medal for his imprisonment during the 1925 Anthracite Strike. On his release, Sammy Morris had been one of the men awarded a medal and a scroll by the ICWPA, and when he set off for Spain in 1936 he was chairman of the miners' union at Rhos Colliery, Ammanford, so he was well known to Jeffreys. Ten years after the Anthracite Strike, there was another major political disturbance in Ammanford – the 'Bus Strike' of 1935 – over union recognition at a local bus company, and where Sammy Morris was again arrested. Of the three to four hundred people present at a riot on Ammanford Square, 18 were subsequently recognised and arrested, and of the 15 actually convicted for public order offences, 11 were members of the local Communist Party. During the hearing at Carmarthen Court on January 5-6th 1936 it became clear that much of the antagonism was caused by a feud between local police, in particular a P.C. Prout, and local communists. On this occasion the 15 who were convicted were found guilty only of unlawful assembly and had to pay £5 costs each. During the trial the octogenarian magistrate had seemed more concerned about the presence of a red flag at the disturbance than the actual charges. A short time after the trial the magistrate died, and Sam Morris and fellow rioter W J Davies (Will Castell Nedd) planted a red flag on his grave. A note was attached: "The Red Flag, found too late". (Story told to Hywel Francis by W J Davies in 1970, and quoted in 'Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War', Hywel Francis, 1984, page 73.)

Of the 11 communists convicted no less than six had been previously arrested during the Anthracite disturbances of 1925. Three of the arrested later served with the International Brigade in Spain, Sammy Morris being one of them. (To see a fuller account of the 1935 Bus Strike, click HERE.)

Because of his brother's involvement in these two disturbances, Theo Morris would have to wait until after the war before he was able to get a job, and even then it would be in distant Tumble colliery, where the mine manager decided to stand up to Jeffrey's bullying and refused his demands to dismiss him. (The information about Theo Morris was kindly provided by his son, David Morris, in 2004.)

Despite Sammy Morris's hostility to religion, amongst the many letters of condolence written to his mother after his death at the battle of Brunete on 17th July 1937 was this one from Ammanford Congregationalist minister D. Tegfan Davies:

"Dear Mrs. Morris, Exceedingly sorry to hear of your sad bereavement. I called last week but you happened to be out at the time. I was very fond of poor Sam – always kind, polite and cheerful. Kindly accept my deepest sympathy. May God bless and comfort you abundantly. Yours faithfully, D. Tegfan Davies." (Letter addressed from Weston Super Mare, 18th Aug. 1937.)

A brief biography of the Reverend D. Tegfan Davies can be found in the 'People' section of this website or click HERE.

4. OBITUARIES: SAMMY MORRIS AND JACK WILLIAMS

The obituaries of Sam Morris and Jack Williams were published in Ammanford's local newspaper, the Amman Valley Chronicle, within two weeks of each other:

Sam Morris, one of the four Ammanford volunteers in the International Brigade has been killed on active service on the Madrid front.

....The news of his death was officially announced during the weekend. He was only 29 years old.

....Sam Morris left for Spain in early December, his heart hardened against the entreaties of those near and dear to him, and adamant in the face of the appeals of his friends. His mind was made up. He was not an adventuresome lad, thoughtlessly embarking on yet another mad-brained prank, but a man of mature discretion, who had carefully weighed all the consequences which might be attendant on his action. It might be said that it was a turning point in his life.

....The Spanish Civil War had raged for nearly six months when he made his decision, irrevocable as it was to prove, and seeing that the struggle had now developed into a fight for national independence against the armies of the corporate states, he espoused the Government cause.

....Not at any time was he forgetful of those he loved far from the battle's roar; and, in spite of his preoccupation as a soldier of Democracy, he took advantage of each break to write those notes, trivial maybe in content, yet eagerly looked forward to by those he had left behind in the dear Homeland, and whose fight he was waging to the fullest extent of his powers.

.... Christmas 1936 he received his baptism of fire on the Madrid Front and, badly wounded in the leg, was laid up in military hospital for three months. Never once in his letters is there any hint of complaint or discontent with his lot. To his family he appears cheerful, although experiencing great pain with his leg. He declines to return home. "Not," he says decisively, "until we stop International Fascism or I am wiped out." That indomitable spirit, so eminently typical of the man, finds its greatest expression in his return to active service shortly afterwards.

.... The end came a few weeks ago. Jack Williams, of Walter Road, Ammanford, his comrade in arms, was with him when he died. (Amman Valley Chronicle, 12th August 1937).The obituary of Jack Williams, in whose arms Sammy Morris had died, appeared a fortnight later:

Official notification was received at Ammanford on Saturday of the death in action in Spain of John Elwyn Williams, third son of Mr. and Mrs. Rees Williams, 45 Walter Road. He was the last of the four Ammanford volunteers who left to join the International Brigade to fight on the side of the Spanish Government on the Madrid Front.

.... Since enlisting in the International Brigade in the second week of April last, Williams had shared the fortunes and setbacks of the Civil War with Sammy Morris, who was killed a few days before him.

.... Both were members of the local branch of the Communist Party and they were firm friends.

.... A carpenter by trade, Williams was acknowledged to be a splendid craftsman.

.... A memorial service to both will be held in September. (Amman Valley Chronicle, 26th August 1937)MEMORIAL MEETING

AMMANFORD MEN

WHO DIED IN SPAINNearly seven hundred people of varying shades of political opinion attended the memorial meeting held at the Minor Hall last Sunday evening, to honour the memory of the late Sam Morris and Jack Williams, two volunteers in the International Brigade, who were killed on the Madrid Front.

.... From the standpoint of numerical strength and keen interest shown, the gathering left little to be desired, and must have been a bitter blow to the critics who claim the working class are fundamentally incapable of solidarity.

.... Speakers were Isobel Brown, London; Arthur Horner, President of the South Wales Miners' Federation, and T.E. Nicholas, Aberystwyth. Councillor Evan Bevan, Saron, presided. (Amman Valley Chronicle, 16th September 1937.)

5. THE INTERNATIONAL BRIGADES

The idea of an international force of volunteers to fight for the Spanish Republic was initiated by Maurice Thorez, the French Communist Party leader in July 1936, in response to the insurrection by Franco and fellow military leaders. Then, in September 1936, the formation of the International Brigades began in earnest and a multi-national recruiting centre was set up in Paris with a training base at Albecete in Spain.

A total of 59,380 volunteers from 55 countries served during the Spanish Civil War. This included the following (in alphabetical order): American (2,800), British (2,100), Canadian (1,000), Czech (1,500), French (10,000), German (5,000), Hungarian (1,000), Italian (3,350), Polish (5,000), Scandinavian (1,000), and Yugoslavian (1,500). These men were organized into the 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th of the Mixed Brigades (the Ammanford volunteers served in the 15th Brigade). Women were also active supporters of the International Brigades, a large number of whom volunteered to serve in medical units in Spain during the war. Volunteers came from a variety of left-wing groups, but the Brigades were always led by Communists. This created problems with other Republican groups such as the the Anarchists and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM), who were Trotskyites.

The International Brigades played an important role in the defence of Madrid in November 1936. They also suffered heavy losses at Jarama (February 1937), Brunete (July 1937), Teruel (December 1937) and Ebro (July-August 1938).

Of the 59,380 volunteers, 9,934 (16.7 per cent) died and 7,686 (12.9 per cent) were badly wounded. It's estimated that 10 percent of all combatants from both sides died in the war, a far higher proportion than is usual even in modern warfare.

6. THE BATTLE OF BRUNETE

On 6th July 1937, the Popular Front government launched a major offensive in an attempt to relieve the threat to Madrid. General Vincente Rojo sent the International Brigades to Brunete, challenging Nationalist control of the western approaches to the capital. The 80,000 Republican soldiers made good early progress but they were brought to a halt when General Francisco Franco brought up his reserves. Fighting in hot summer weather, the Internationals suffered heavy losses. Three hundred were captured and they were later found dead with their legs cut off. All told, the Republic lost 25,000 men and the Nationalists 17,000.

July 1937 also saw the British Battalion, now under the command of Fred Copeman, thrown once more into battle as part of a major Republican offensive designed to relieve pressure on the northern front and break through the rebels at their weakest point to the west of Madrid. On the 6th July, the British Battalion moved towards their objective, the heavily-defended village of Villanueva de la Cañada, which Spanish Republican forces had been unable to secure. The battalion was pinned down by well-directed machine-gun fire, and forced to take cover, short of water and in temperatures of 40 degrees, and wait until nightfall. The village was captured eventually at midnight, though not before a number of volunteers were killed when Rebel soldiers attempted to escape by using civilians as human shields.

The following morning, almost a day behind schedule, the battalion moved forward towards their major objective, the heights overlooking the Guadarrama River, and the village of Boadilla del Monte, where British members of the Thaelmann and Commune de Paris Battalions had fought six months earlier. But weakened by fatigue, thirst and constant bombardment from the air, they could not advance sufficiently rapidly to capture the unoccupied heights and Rebel forces quickly took the opportunity to move into the position. Of the three hundred and thirty-one volunteers in the ranks of the British Battalion at the start of Brunete, only forty two still remained at the end, Ammanford's Sammy Morris and Jack Williams being among those who perished. Whether they met their death by bullet, bayonet, bomb or shell blast, or they were among those three hundred prisoners mutilated before death, is unknown to this day.

7. THE BOMBING OF GUERNICA

In a letter to his mother in Ammanford dated 28th February 1937, Sam Morris had written of the German bombing of Spanish towns, but the most infamous attack on a defenceless town and its population was yet to come. It was market day in Guernica in the Basque region of Spain when the church bells of Santa Maria sounded the alarm that afternoon on 26th April 1937. People from the surrounding hillsides crowded the town square. 'Every Monday was a fair in Guernica,' says José Monasterio, eyewitness to the bombing. 'They attacked when there were a lot of people there. And they knew when their bombing would kill the most. When there are more people, more people would die.'

For over three hours, twenty-five or more of Germany's best-equipped bombers, accompanied by at least twenty more Messerschmitt and Fiat Fighters, dumped one hundred thousand pounds of high-explosive and incendiary bombs on the village, slowly and systematically pounding it to rubble.

'We were hiding in the shelters and praying. I only thought of running away, I was so scared. I didn't think about my parents, mother, house, nothing. Just escape. Because during those three and one half hours, I thought I was going to die.' (eyewitness Luis Aurtenetxea)

Those trying to escape were cut down by the strafing machine guns of fighter planes. 'They kept just going back and forth, sometimes in a long line, sometimes in close formation. It was as if they were practicing new moves. They must have fired thousands of bullets' (eyewitness Juan Guezureya). The fires that engulfed the city burned for three days. Seventy percent of the town was destroyed. It is estimated that 1,685 civilians – one third of the population – were killed and 900 injured in the attack.

News of the bombing spread like wildfire. The Nationalists immediately denied any involvement, as did the Germans. But few were fooled by Franco's protestations of innocence. In the face of international outrage at the carnage, Wolfram Von Richthofen (nephew of the legendary 'Red Baron' of World War 1) claimed publicly that the target was a bridge over the Mundaca River on the edge of town, chosen in order to cut off the fleeing Republican troops. But although the Condor Legion was made up of the best airmen and planes of Hitler's developing war machine, not a single hit was scored on the presumed target, nor on the railway station, nor on the small-arms factory nearby.

Guernica is the cultural capital of the Basque people, seat of their centuries-old independence and democratic ideals. It has no strategic value as a military target. Yet some time later, a secret report to Berlin was uncovered in which Von Richthofen stated, '... the concentrated attack on Guernica was the greatest success', making the dubious intent of the mission clear: the all-out air attack had been ordered on Franco's behalf to break the spirited Basque resistance to Nationalist forces. After the war a telegram sent from Franco's headquarters was discovered and revealed that he had asked the German Condor Legion to carry out the attack on Guernica. Guernica had served as the testing ground for a new Nazi military tactic – saturation-bombing a civilian population to demoralize the enemy. It was a wanton, man-made holocaust. "Condor Legion officers regarded the war as a fascinating and important laboratory experiment; their technicians invented the napalm bomb, for example." (The Spanish Civil War, Antony Beevor, Cassell Paperback, 1999, page 283).

Note: On May 12, 1999, the New York Times reported that, after sixty-one years, in a declaration adopted on April 24, 1999, the German Parliament formally apologized to the citizens of Guernica for the role the Condor Legion played in bombing the town. The German government also agreed to change the names of some German military barracks named after members of the Condor Legion. By contrast, no formal apology to the city has ever been offered by the Spanish government for whatever role it may have played in the bombing. (From: www.pbs.org)

8. PICASSO'S GUERNICA (OIL ON CANVAS, 11.45 x 25.46 Feet)

The most famous image of the Spanish Civil war is not a photograph, but a painting by the twentieth century's greatest artist, Pablo Picasso. At the start of the Spanish civil war, Picasso, in his mid-50s, was living in France. The Spanish Republican government had commissioned a large work for the 1937 International Expo in Paris. Then came the atrocity of Guernica. The picture took six weeks. At its first showing in the Spanish pavilion, Guernica was hung more or less in the café area, with folk dance troupes performing in earshot. Then it began its travels, touring to raise support for the republic. At the London Whitechapel Gallery exhibition in 1938, 'ranks of working men's boots were left at the painting's base: the price of admission was a pair of boots, in a fit state to be sent to the Spanish front'. (Whitechapel residents were not to know when they gazed on Picasso's paining in 1938 that in just two years time the very same German air force that bombed Guernika would do much, much worse to them and the rest of London's East End during the 'Blitz' phase of World War Two.)

But the Spanish republic was falling fast, and Guernica soon found itself the property of a non-existent state. For decades it was housed in the Museum of Modern Art, New York. In 1981, after tortuous negotiations, it finally returned 'home' to post-Franco Spain, a home where it had never in fact been. On the centenary of Picasso's birth, October 25th, 1981, just six years after Franco's death in 1975, Spain's new government (by now a constitutional monarchy, but not the republic Picasso had supported) carried out the best commemoration possible: the return of Guernica to Picasso's native soil in a gesture of national reconciliation. It now hangs in Spain's national museum of modern art, the Reina Sofía in Madrid, one of the most viewed paintings in the world.

A modernist image of pain and brutality depicts the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in 1937. (Oil on canvas, 11.45 x 25.45 feet.) For a fuller history of the painting see: www.pbs.org

9. THE BLOCKADE RUNNERS AND 'POTATO' JONES

David 'Potato' Jones was one of three Welsh sea-captains who ran goods – and guns – to northern Spain for the opponents of Franco during the Spanish Civil War. All three were called David Jones – nicknamed "Potato", "Corn Cob" and "Ham 'n' Chips" Jones to distinguish them. Potato Jones, the dominant character among them, was in his late fifties by the time of the war. He had gone into business with a Swansea landlady, Edith Scott, and they owned three tramp steamers: the one that Potato Jones himself skippered was the Marie Llewellyn. Potato Jones had a cargo of potatoes under which were hidden the guns that he ran to Spain from Rotterdam. He was reputed to have broken the blockade set up by Franco at Bilbao. In fact he did not: the reporters got their facts wrong – it was another skipper, William Roberts, captain of the Seven Seas Spray, who broke the blockade. However, Potato Jones did take part in moving thousands of refugees from Spain to safety in France after the Republican defeat in 1939.

Surviving crew members of of the British battle cruiser, HMS Hood, have left memories of their service days on the Hood Association website. This one is from Leonard C. Williams who remembers an incident involving 'Potato' Jones:

Our patrol in 'Hood' was between Gibraltar, Tangier, Palma and Marseilles. Occasionally it would be brightened by an odd incident such as the time when 'Potato Jones' ran the Spanish Blockade to land his cargo of potatoes to the besieged population of Bilbao. On this occasion 'Hood' was in Gibraltar, and half of us were ashore on night leave. We received an urgent signal from the Admiralty to proceed at full speed to the Bilbao area to give protection to 'Spud Jones' and his ship which was being threatened by a Spanish cruiser.

.....The recall flag was flying from the yard arm, and periodically 'Hood' blasted her syren to attract the attention of the men still onshore, of whom I was one. We libertymen hurried down to the harbour and got back onboard. The ship sailed at 5 a.m. and, at 25 knots we belted out of the Mediterranean, and turning northwards, headed for Bilbao, arriving off the port at 7 a.m. next morning.

.....On arrival we found a large Spanish cruiser and 'Spud Jones's' steamer within hailing distance of each other. Spud himself always wore a bowler hat, and we could see him on his bridge gesticulating to the Spaniard. We received a signal from him to the effect that the 'Blankety Blank' cruiser was stopping him from going in to Bilbao to unload his potato cargo, which, by this time, was beginning to go rotten.

.....Attached to 'Hood' at this time were the Home Fleet destroyers 'Firedrake', 'Fortune' and 'Flame', and we informed Jones that he could proceed into Bilbao and that the three destroyers had been detailed to escort him in. Thumbing his nose to the Spanish cruiser, and with a puff of dirty black smoke from his steamer's funnel, 'Spud Jones' went on his way with a destroyer on either side of him and another leading the way. 'Hood', with her crew at action stations, circled the cruiser to prevent, any further interference.

.....'Potato Jones' was a persistent old cuss, and on more than one occasion he and his ship had to be got out of scrapes; but he and his ilk were the salt of the earth. He had the freedom of the ocean, and he wasn't going to be kicked around by Spaniards or anybody else! (From the HMS Hood Association website: http://www.hmshood.com/crew/bios)Another Hood crew member who remembers 'Potato' Jones is Dick Turner:

We got up to St. Juan de Luz just as another small convoy of British ships was being assembled. One of the merchant Captains, known to the men in Hood as 'Potato Jones', indicated that he was going to make the run to Bilbao. Sure enough there was an incident as 'Potato Jones' approached the port of Bilbao, but Hood's presence seemed just enough to tip the balance against the Insurgents [ie Fascists] taking action and Jones managed to get through. Bilbao itself fell to the Insurgent forces fairly soon afterwards so that was the end of that situation. (From the HMS Hood Association website: http://www.hmshood.com/crew/BIOS)

The blockade runners often took great risks bringing much needed food, supplies, and even arms to the beleaguered Spanish Republic, but it needs to be remembered that their motives were commercial more often than not. The Republicans, the legal government of Spain, were still dependent on Britain and other nations for their needs, and the blockade runners were well paid for their services. The Spanish government was offering much higher rates than normal for supplies crucial to their survival, an opportunity many companies in South Wales were quick to seize. The Civil War years in fact saw a revival in the fortunes of many shipping companies, and even the creation of some new ones. While Cardiff was the main point of embarkation for these goods in South Wales, other ports like Newport, Barry, Swansea and Port Talbot were also used.

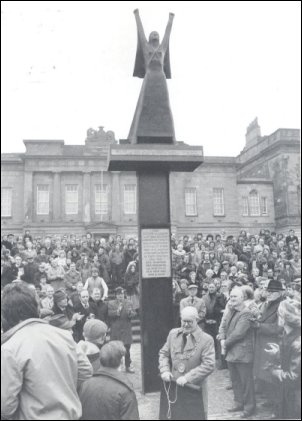

10. BRITISH MEMORIALS TO THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR

There are currently about 50 memorials in the British Isles to volunteers who died fighting with the International Brigades in Spain, and others are being planned. The memorials range from small-scale gestures to much larger and ambitious statements of appreciation. A couple of the memorials are modest park benches, a brass plate bearing the name of the volunteer who died. Most are plaques in various buildings, such as libraries and trades union headquarters, and there are large statues in prominent public places. The memorial at St. Luke's Church in Peckham, London, is a red stole (clergy scarf) embroidered with the symbol of the International Brigades, and worn by the vicar for sermons on various martyr's days. Waterford in Ireland produced a commemorative booklet in 2004. Here is a table with the known memorials:

WALES Ammanford; Aberdare; Burry Port; Caerleon; Caerphilly; Cardiff; Llanelli; Merthyr Tydfil; Neath; Porthcawl; Rhondda; Swansea. IRELAND Achill, Co. Mayo; Dublin; Morley's Bridge, Co. Kerry; Waterford. SCOTLAND Aberdeen (3 memorials); Glasgow (2 memorials); Edinburgh; Kirkaldy; Dundee; Prestonpans (2 memorials); Irvine. LONDON Jubilee Gardens, Waterloo, South Bank; International Brigade Association (IBA), Clerkenwell; Transport & General Workers Union (TGWU), Transport House, Holborn; Unity Theatre (destroyed by fire), St. Pancras; Camden Town Hall; Southwark Town Hall, Peckham; St Luke's Church, Peckham; REST of ENGLAND Newcastle upon Tyne; Middlesborough; Liverpool; Manchester; Oldham; St. Helens (2 memorials); Halifax; Rotherham; Leeds; Sheffield; Hull; Stoke-on-Trent; Nottingham; Nottingham; Birmingham; Leicester; Reading; Canterbury; Swindon; Rottingdean; St Albans. Here are just two of the above memorials:

According to one theory, well intentioned no doubt, we're supposed to learn from the lessons of history in order to shape the future better. If so, then we've not done too well in the decades since Spain, and Iraq alone should highlight this failure most poignantly.

11. INTERNET LINKS TO RELATED WEBSITES AND BOOKS

International Brigade Memorial Trust (IBMT) This is the main website about the British volunteers who fought in the International Brigades. The IBMT is formed from veterans of the International Brigade Association (IBA) and the Friends of the IBA, and the website includes on-line copies of their quarterly newsletters. The President is Jack Jones, former British Trades Union leader who also fought in the Spanish Civil War himself. Welsh Memorials to the International Brigades A bilingual website in English and Spanish, consisting of photographs of memorials in Wales to those who died in action. It contains useful links to other websites about the Welsh involvement in the Spanish Civil War. Also contains a free downloadable booklet, with photographs, about the Welsh memorials. To download it direct click HERE. Map of the locations of Memorials A map with further details of the memorials and their locations can be found on this website of the International Brigade Association (IBA). Click to get the map and click again on a region to see a list of the memorials in that area. Spanish Civil War Enactment Group, La Columna "La Columna is a UK based re-enactment group commemorating and celebrating the international volunteers who went to fight alongside the Spanish people in defence of the Second Republic during Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. La Columna is a non-political organisation but with strong sympathies for the Spanish Republican cause of the late 1930s." (From La Columna website} Spartacus Educational website Useful site containing a wealth of material, including a chronology from 1930 to 1939, a history of the International Brigades, and biographies of a number of volunteers. They Shall Not Pass The London Guardian's tribute to the volunteers, published on November 10th 2000. Includes an introduction by Ian Aitken, Guardian columnist and son of British volunteer George Aitken; interviews with 23 of the surviving 40 British veterans; and photographs by portrait photographer Eamonn McCabe. Song: Miners Against Fascism Ammanford singer-songwriter Tracey Curtis has a song called Miners Against Fascism which documents the campaign and actions of radical Amman Valley miners throughout the 20th century. The song can be downloaded for free by clicking HERE. Secondary Wars and Atrocities of the Twentieth Century Included amongst this grim set of statistics are estimated casualties for the Spanish Civil War. Scroll down to item 12, Spanish Civil War. Memorials of the Spanish Civil War Book of photographs and stories of all the memorials in the British Isles (up to 1996). Edited by Colin Williams, Bill Alexander and John Gorman; Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd.; 1996. Miners Against Fascism Miners Against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War, Hywel Francis, 1984. The first major study of of the Welsh volunteers who went to Spain. The Battle for Spain By Antony Beevor, 2006. Revised and updated from a 1982 edition to include recent material released from Spanish and Soviet Union archives. Acknowledgment: The letters quoted from above were kindly provided in 2004 by Mr. David Morris of Ammanford, the nephew of Sammy Morris, and the son of Theo Morris.

Date this page last updated: October 1, 2010