CONTENTS (1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary. (1) Introduction

Until the mid-eighteenth century education in Ammanford, as in the rest of Wales, was essentially non-existent for most people. Then, starting with charity schools provided by churches, chapels and wealthy benefactors, we finally arrived at the current system of free education for all up to eighteen years of age, provided by means of nursery, infants, primary and secondary schools funded by local councils. What follows is a brief history of that process in the parish of Llandybie from the 1730s onwards.

That journey, far from being inevitable, was a long and tortuous process whose final result shouldn't be taken for granted. It follows the great curve of history as it sweeps along three hundred years of struggle to obtain what only fairly recently has become a fundamental human right. And even as recently as 1881, secondary school educational provisions for the children of the working class in Wales was pathetic to the point of being almost non-existent:

At any level above the elementary, Wales was ill-catered for. The departmental committee under Lord Aberdare appointed by Gladstone to enquire into Welsh secondary and higher education, reported in 1881 that only 1,540 children in Wales enjoyed any kind of secondary education with a further 2,946 at private and proprietary schools such as Llandovery College, Christ's Church at Brecon, Howell's School at Denbeigh and Friar's School at Bangor. Broadly speaking, the Aberdare Education Committee sympathetically but convincingly recorded that most Welsh children had no educational opportunity at all above the most elementary level. They were doomed to the same routine of mindless manual work of their parents and grandparents. By implication, the quality of Welsh life, its leadership in the professions, in the arts, in commerce and industry, within the circumscribed world of the nonconformist pastorate, remained diminished. (Rebirth of a Nation: Wales 1880–1980, Kenneth O. Morgan, Clarendon 1981, page 23-24)

(1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary. (2) The Circulating Schools.

The 'Circulating Schools' was the great movement of the eighteenth century and it was unique to Wales. It's worth making a digression to understand this movement, as the circulating schools were the first — and at the time, the only — schools for the children of the 'poorer sort'. It's also worth noting that adults often made up the majority of the pupils at these schools and could make up two thirds of pupil numbers. These adults attended night schools after their day at work, which in those days was mostly agricultural. Pensioners, too, are recorded as being pupils. John Davies, in his "History of Wales (Penguin 1993), writes of these schools thus:

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, popular literature was an oral tradition, but it was increasingly overtaken by the printed word. The first publication of the press founded by Isaac Carter at Atpar near Newcastle Emlyn in 1717 (the earliest permanent printing press on Welsh soil) was a ballad in praise of tobacco, a foretaste of the abundance of ephemera which was to flood from the presses of Wales in subsequent generations.

.... These developments suggest that literacy in the Welsh language was spreading rapidly by the middle decades of the eighteenth century. That was the period of the great campaign of Griffith Jones of Llanddowror to endow his compatriots, as quickly as possible, with the ability to read their mother tongue. Griffith Jones (1683 - 1761) was a farmer's son from the Teifi valley, one of the most cultivated districts of Wales. In his youth, he had a religious experience so intense that he was overwhelmed with the desire to save souls. His career was strongly influenced by Sir John Philipps [the squire of Picton Castle near Llandeilo]; in 1708, Jones began to keep a school under the auspices of the S. P. C. K. (The Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge). He became a correspondent of the society in 1713, Sir John presented him to the living of Llanddowror in 1716 and he married the baronet's sister in 1720 ...

.... Although highly talented as a preacher, Griffith Jones considered that sermons in themselves did not suffice, and that there was a need to ensure that the mass of the population had a firm grasp of the Christian religion through indoctrinating them with the catechism and through enabling them to read the Bible. In about 1734, when he was over fifty and in poor health, Jones devised a scheme for establishing temporary schools which would concentrate entirely upon teaching children and adults to read their mother tongue. Every feature of the plan for circulating schools had been at least suggested before. Griffith Jones had little originality: what he did have was the energy and single-mindedness to fulfill his aspirations. He received the enthusiastic support of Bridget Bevan of the Vaughan family, squires of Derllys near Carmarthen. Her links with wealthy patrons in London and Bath were an important element in his success, for England was the source of most of the money which went to pay the meagre wages of the teachers and to buy reading materials for the pupils. Griffith Jones sent an annual report, Welch Piety, to his patrons; in it he appealed for funds, noted the progress of the campaign and sought to allay any doubts concerning his efforts. One of the chief doubts arose from his emphasis upon the Welsh language, for, outside anglicized areas such as south Pembrokeshire, the circulating schools were conducted in Welsh. The argument he presented to his English patrons was the practical necessity for teaching through the mother tongue, although Griffith Jones certainly had a warm affection for the Welsh language. He also emphasized that the language was a barrier which prevented the Welsh from adopting dangerous ideas and loose morals, for to him as to almost all Welsh patriots, at least until the late eighteenth century, the Welsh language was a weapon of reaction.

.... Welch Piety provided details year by year of the number of pupils attending the circulating schools. They can be interpreted to imply that over two hundred thousand people, almost half the population of Wales, had attended them by 1761, the year of Griffith Jones's death. The work continued under Bridget Bevan until her death in 1779. The circulating schools were at their most numerous in the three south-western counties, where there were districts in which schools were held and held again over a quarter of a century and more. But apart from Flintshire, where there was virtually no campaign, numerous classes were held in all the counties of Wales and they were warmly praised by northerners such as William Morris of Holyhead and Robert Jones of Rhos-lan. The circulating schools offered a very limited education and the reading materials used in them were heavily pietistic. Griffith Jones stressed that he did not wish the pupils to have ideas above their station. 'The purpose of this spiritual charity,' he wrote, 'is not to make gentlemen, but Christians and heirs to eternal life.' His efforts led to a fundamental transformation of the life of Wales. By the second half of the eighteenth century, Wales was one of the few countries with a literate majority. Griffith Jones's schools aroused interest outside Wales, and do so still; Catherine, empress of Russia, commissioned a report on them in 1764 and they were suggested as a model by UNESCO in 1955. (John Davies, "A History of Wales, Penguin 1993, pages 306-307)A more statistical account of Griffith Jones's achievement is provided by another historian:

By his death in 1761, aged 77, Griffith Jones had been responsible for establishing 3,325 schools in nearly 1,600 different places in Wales. The total number of pupils — both adults and children — who were taught to read fluently in his schools may well have numbered 250,000, an extraordinary achievement, given the fact that the population of Wales was around 490,000 at the time. (Geraint H Jenkins, The Foundations of Modern Wales 1642 - 1780, Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press 1987, page 377)

Gomer Roberts in his 'Hanes Plwyf Llandybie' (History of the Parish of Llandybie, 1939) can take up the story from here:

The first reference to education in the parish of Llandybie is in the report of the wardens to Bishop Laurence Wornock in 1684, where it states, "one Griffith Rees keeps a school, but whether he is licensed or no we know not" This was the first known school in the parish, but we do not know where it was held, and we know nothing, either, of the schoolmaster.

....The great educational movement in Wales, of course, was the movement of Griffith Jones, Llanddowror, known as the "circulating schools" and this area was fortunate in its early connection with Griffith Jones. This is proved by his correspondence with Madam Bevan; he wrote to her on October 2nd 1736, "I had a very agreeable journey to Llanlluan Chappel and back again. I took a couple of the clergy I met there for 2 or 3 miles with me in my return for the sake of talking together; and are to meet again next Wed. night at Carmarthen, to converse a little more together. One of them I think, is better than common, I mean Griffiths of Bettws ..." Jonathan Gryffies, curate of Bettws was the man mentioned (he also served in Llandybie).

.... According to the "Welch Piety", there was a school in Llandybie in 1738-39, with 54 scholars, as well as one in Llanlluan and Bettws. We can also gather from his letter to Howell Harris, dated January 13th 1738, that Anthony Rees was the schoolmaster in Llandybie. He told the Revivalists of Trefecca that he had 48 scholars, and Jonathan Griffies of Bettws had 56, and he confessed to his hero that he exhorted his scholars as much as he taught them.

.... In the 1748 report, the wardens stated: "No public school, but a petty school for young beginners; the teacher behaves himself soberly, and brings up his pupils according to the liturgy of the Church of England." Something similar is the report signed in 1755 by Thomas Rees, the vicar, "We have no publick or Charity school, but a small petty school."

.... In the "Welch Piety" there are letters from men of the parish giving a report of the work of the school, and as they throw a light for us on the characteristics of the circulating schools and the manner in which they carried on, I shall place them before the reader. The first we see is from "a gentleman promising very kindly to inspect the school he desires," Thomas Evans of Aber-Lash. Here is his letter:ABERLASH IN LLANDEBYE, CARMS.

March 17, 1759.Sir,

The Inhabitants of the Parish of Llandebye being sensible of the manifold Advantages arising from the Welch Charity Schools have at their parish Meeting, held last Tuesday, enjoined me to return you, and the worthy supporters of that laudable Institution, their grateful Thanks for the apparent Good the poor Children of this Parish have already had and reaped from the Inestimable Benefaction.

.... The Behaviour of the Children in Church, readily making their responses in the Church Catechism, and keeping the Sabbath holy are admitted to be Blessings which they would not, in all Probability have attained had you not given us a Welch Charity School. The present Master I L has been very assiduous and gave due attendance on the Children. Therefore it is humbly requested that we may have him yet another Quarter in this Neighbourhood, where there are many poor Children, who have not, through the poverty of their Parents and want of Proper Raiments, been able to attend in the upper Part of the Parish where the late school was kept If the request may, according to the rules prescribed, be granted, I am satisfied you do a good and laudable Service to those poor, unhappy, young Fellow-Creatures who now are, and otherwise may continue in an entire State of Ignorance. If we are so happy as to succeed in our joint Petition, it shall be my care to inspect the future Behaviour of the Teacher; and that he does Justice to his and our Benefactors, whom God of his infinite Mercy grant, may have their Reward in this World, and that which is to come,

I am etc., Thomas Evans.The school being referred to was held in Glun-Glas in the upper part of the parish, and the petition succeeded, because in the following year there were schools in the parish, held in the church, and Myddynfych, and another in Blaenau a year later. It is a pity that we do not have the master's full name. The curate wrote again before the end of the same year to thank for the favour, and here is his letter:

LLANDEBYE,

Nov. 24, 1759.

Reverend Sir,I have once more the pleasure of acquainting you that the Favour of a Welch School in our neighbourhood, is, through the divine Influence, become a public Blessing. The happy Tendency of which Method to promote its great and Important End is now so obvious that any further Enlargement on the Subject is entirely needless; and Prejudice which the carnal World thought proper to entertain against it, are, as far as my converse in the same tells me, almost thoroughly removed. May the great God have the whole Praise thereof.

....About Thirty of the children belonging the School at Cwmpedol have been Twice publicly examined by me at Llandebye Church, where they acquitted themselves with so much Propriety and Freedom in repeating the Catechism, the Graces and Prayers and singing of Psalms as gave uncommon satisfaction to the whole Auditory.

....A visit afterwards into the School gave me the following account of their Progress; Twenty Four were reading 'The Exposition of the Catechism'; Forty Eight could repeat the Catechism perfectly well; Nineteen were getting the Prayers by heart; Fourteen could repeat them; Fifty could make responses at Morning and Evening Prayers; and Sixty Six could say the Graces before and after Meat exceedingly well. Such a proficiency, and in so short a time, is an incontestable proof of their Tutor WJ's Ability in his Station but his Integrity as a Schoolmaster and his Piety as a Man, are so well and universally known, as not to need any further recommendatory Words. But I cannot forbear mentioning that his Pains in instructing his Pupils in the Principles and Rudiments of the Religion of Jesus, are indeed indefatigable and successful. This Second Quarter is now commenced, and has favourable and promising aspects.

....May the God of Mercy bless all such Pious Endeavours, and may everyone that concurs therein partake of the Blessing of Time and Eternity, is the sincere and ardent Prayer of etc.John Thomas.

Curate of Llandebye.It can be seen by the above letter that he is referring to a previous one which appeared in the "Welch Piety" dated June 20th 1759. This mentions the public examination of the students of the Welsh school, and the high praise in the 'round about' language of the period to the schoolmaster S. L.…. There was another letter from the above John Thomas, dated May 23rd 1760, in which he gives a report about a school containing 61 students at Llwyn-yr-Haf. The last letter I saw was one from the Rev. Thomas Davies, curate of Llandybie, and in this, he gives the name of the schoolmaster as William John; I suggest that this man was William John, Glancothi (he had been a councillor with the Methodists in his day). Here is the letter: -

LLANDIBIE IN CARMARTHENSHIRE,

Jan. 22, 1766.Madam,

This is to certify that William John has discharged his Duty as a Welch Schoolmaster, in this Parish, to the universal Satisfaction of the Inhabitants; That having visited his School, and examined his Scholars, both in the Church Catechism and the Exposition thereon, I can assure you, Madam, that nothing can better testify his Care and Diligence, than the surprising Progress his Scholars made in so Short a Time. He had last Quarter under his Tuition upwards of 70 children; and therefore at the request of the Parishioners, I humbly beg you would give him leave to pursue the School another Quarter; which shall be ever gratefully acknowledged by, etc.Tho. Davies,

Curate of LlandybieIn 'Hanes Plwyf Llandybie' Gomer Roberts provides a list of all the circulating schools held in Llandybie parish under the patronage of the Welsh Charity Schools Movement. The first was held in 1738 in Llandybie with 54 pupils and the last was in 1771, again in Llandybie, at Nantycaglau with 75 in a day school and 40 in a night school. In that 33 years 49 circulating schools are known to have existed in Llandybie parish. Half of them had less than 50 pupils and the largest had 79. And remember, these were temporary schools for three months at a time only, although some schools were repeated. Although Griffith Jones died in 1761 we can see that Gomer Roberts' list ends in 1771 — ten years after his death. The movement did not end with its creator, as Madam Bevan continued Griffith Jones' work until her own death in 1779.

Between 1761 and 1777, 3,325 schools were established, offering education to 153,835 pupils. The peak year was 1773, when 242 schools were set up and 13,205 scholars received instruction. However, most of the gains achieved under Madam Bevan's supervision were made in anglicized communities, notably in the towns of Monmouthshire and Pembrokeshire where pupils were taught through the medium of English. (The Foundations of Modern Wales 1642 - 1780, Geraint H Jenkins. (Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press 1987, page 377)

A protracted legal action after she died sadly showed that the roots of the Circulating Schools Movement were not particularly deep and withered when their founders were no longer there to nurture them.

When Madam Bevan herself died in 1779 and was buried alongside Griffith Jones in accordance with her wishes, she bequeathed her estate of £10,000 to the scheme in order to ensure the perpetuation of the circulating schools. However, two of her trustees challenged the will and the money became tied up in the Court of Chancery for thirty-one years. From this set-back there was to be no recovery. Deprived of essential financial aid, the circulating school system withered and died. (The Foundations of Modern Wales 1642 - 1780, Geraint H Jenkins. (Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press 1987, page 377)

The impetus that propelled education forward — industrialisation — was still in the future. When Griffith Jones opened his first school in 1731, Wales, and indeed the rest of the world, was overwhelmingly rural with an agricultural economy. As late as 1770 Carmarthen, with a population of 4,000, was the largest town in Wales. Within 100 years however there would be a mass stampede from the fields of the countryside to the factories of the towns. What later generations would call the 'Industrial Revolution' — that is, a town-based economy driven by manufacturing and trade — had begun. But manufacturing and trade, unlike agriculture, require an educated workforce, or at the very least a literate and numerate workforce, to operate its machinery and administer its affairs. The new social and economic relationships of industrialisation created skilled workers for the mills, factories and mines who needed at least the basics of reading, writing and arithmetic. And an army of clerks, administrators and managers had to be recruited and educated for industry and the civil service that an advanced industrial power spawns.

But what was taught in these circulating schools, the only education available at the time for the people of Llandybie parish? Not a lot, would have to be the answer, for only reading was taught, albeit the reading of Bishop Morgan's magnificent Welsh translation of the Bible. As Geraint H Jenkins writes:

Many overworked and underpaid clergymen testified that the itinerant schools had served to rejuvenate the church in their localities. The demand for Welsh bibles was seemingly insatiable: when limited supplies of the 1748 edition of the Welsh Bible reached Anglesey, poor people nearly scratched out the eyes of Thomas Ellis, vicar of Holyhead, as they surged forward and fought to acquire a copy; similarly, there was such an extraordinary demand for the Scriptures among the parishioners of the vale of Conwy that poor people borrowed money in order to buy copies. (From Geraint H Jenkins, 'The Foundations of Modern Wales 1642 - 1780', Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press, 1987, page 379)

Writing and arithmetic, however, were subjects deliberately shunned by Griffith Jones. Geraint H Jenkins again:

Much of Griffith Jones's success stemmed directly from his decision to trim severely the curriculum adopted by his predecessors. Part of the price to be paid for instant success was the abandonment of writing and arithmetic, accomplishments which Jones believed were unnecessary and over-demanding in rural communities. He instructed his schoolmasters to offer a rudimentary but practical education by teaching pupils to read the Scriptures, thereby providing them with the means to salvation ... He never considered literacy a tool for acquiring radical opinions or as a vehicle for social change. (Geraint H Jenkins (above, page 372.)

So, salvation and not education was his motive and the vital key to Jones's success lay in his steadfast determination to teach the Welsh-speaking pupils of his schools only through their own Welsh language:

He showed how teachers were able to capitalize on the phonetic advantages of the Welsh orthography to produce literate pupils within a maximum period of three months. The Welsh language acted as a solid barrier against the evils of libertinism and vice, protecting innocent peasants from 'atheism, deism, infidelity, Arianism, popery, lewd plays, immodest romances and love intrigues. (Geraint H Jenkins (above, page 373.)

Although there is no doubt of Griffith Jones's genuine love for his native language, he seems to have been as much concerned to keep children — and adults — from 'unsatisfactory' ideas, most of which were published in English. Griffith Jones may have been Welsh, and a Welsh patriot at that, but he also belonged firmly to the British establishment and shared their hatred of Catholicism, radical ideas and anything else that remotely threatened the status quo.

The circulating schools in Llandybie from 1738 to 1771, as listed by Gomer Roberts in his book, are:

DATES SCHOOL DATES SCHOOL 1738-1739 Llandybie 1759-1760 Blaenau, Llandebie 1740-1741 Rhydyffwlbert, nr Castell Carreg Cennen . Llwynyrhaf, Llandeilo . Pantyllyn, nr Llandybie. 1761-1762 Clynymoch, Bettws. . Felin Farlais, Llanfihangel . Caerbryn, Llandebie 1741-1742 Llandybie. 1763 Caerbryn, Llandebie . Cwmaman, Llandeilo . Night School, Llandebie 1742-1743 Cwmaman, Llandeilo. . Cwmpedol, Llandeilo 1744-1745 Llandybie . Llandebie 1745-1746 Penderi March Llandybie . Llandebie Night Sch 1747-1748 Callifer, Llanaberbythych 1764-1765 Aberpedol, Bettws 1751-1752 Llandyfaen Chapel . Nantybagle, Llandebie, . Ffynnon franddu . Nantybagle . Aberbythych . Nantybagle, Night Sch 1752-1753 Ffynnon Freuddig do. 1766-1767 Llandyfan, Llandeilo. 1755-1756 Gelli'r fawnen, Llandybie . Night School Llandeilo 1756-1757 Cwmaman, Llandebie . Danyrheol Llandeilo . Blaenau, Llandebie . Blaenberygroes , Llandebie . Clynglas, Llandebie . Blaenberygroes, Night Sch . Llwynyrhaf, Llandebie . Glyn, Ll. Aberbythych . Cwmpedol, Llandeilo 1770-1771 Nantycaglau, Llandebie. 1757-1758 Cynglas, Llandebie . Nantycaglau, Night Sch . Llety mawr, Aberbythych. . . 1758-1759 Llandebie Parish Church ... . . Myddynfych, Llandebie. ... . . Cwmpedol, Llandeilo ... . For a fuller account of Griffith Jones and his movement on this web site, click on: 'Griffith Jones and the Circulating Schools'.

(1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School.

We can do no worse than to continue with Gomer Roberts:

By the end of the 18th century, Griffith Jones's movement had faded, and the county was in danger of falling back into ignorance. Yet the people now had a taste for education through this movement, although only "some smattering of letters," argued Thomas Bartley, was the limit of the majority. By the beginning of the next century, two things came to fill the gap, the Sunday schools, and the private schools.

.... Sunday schools started in these areas around 1807. Here is a list of all the Sunday schools in the parish, with the year each one was established, and the number of persons attending regularly:

Name of the School Blaenau (Church) Llandybie Church Gallery Saron Chapel (Baptist) Soar Llandyfan. (Baptist) Cross Inn Chapel (Independent) Capel Hendre (Methodist) Llandybie Chapel (Methodist) Wesley Chapel We learn more in the reports about the manner of teaching in different schools. There were four teachers in the Wesleyan school and the method of teaching was to take the children one by one. The teachers were laymen, and after two hours of schooling (in Welsh and English), everyone went to the service. The arrangements in Capel Hendre were also similar. In the gallery of the church there were two men and two women teachers, and one of them received a wage, the vicar taking care of the expenses. They adopted the individual method of teaching the children, the vicar teaching the catechism, and the curate keeping control over the children. The Calvinistic Methodist school was Welsh only, the individual method again of teaching, with two hours of schooling, and laymen as teachers. Nearly all the pupils of this school lived a mile and a quarter from the chapel, and about half of them attended the service afterwards. There were eight teachers in Saron, and the minister and laymen gave instructions in Welsh; two and a half hours was the length of time in this school, and all went to the service afterwards. In the Cross Inn (ie Ammanford) there were eight teachers; the individual system, and the minister assisting. They used Welsh and English, and the length of time was two hours. In Llandyfan there were six teachers instructing in the two languages; the children learnt hymns as well as elementary books. The lessons were for one and a half hours, and they were questioned on the lesson at the end, and the school period closed with a hymn. Three women teachers were at Blaenau, using the individual system the vicar teaching the catechism. Here too, there was Welsh and English, and the 'ladies' of Blaenau were in charge.

.... The whole total number of pupils was 454 – 85 church members, and 369 nonconformists, out of a population of 2,534 in the parish. That was the testimony of the 'Blue Books' on the Sunday schools.

.... Towards the year 1819, details were prepared about the educational facilities of every parish in the county for the 'Select Committee' that was dealing with the educational problem at that time. Here are the details about the parish of Llandybie:

.... Population: 1,787. Endowments: None. Other Schools: A Boarding Day School and a Sunday School supported by charitable subscriptions, the former containing fifty, and the latter sixty children. (John Williams: Vicar).

.... I believe the "Boarding School" to be Piode school, and the second to be the Wesleyan school. There were five schools in the parish according to the report of the 'Blue Books'.

(1) The Church School: This was established in 1786, and was kept in the loft of the church under the care of the vicar. The building was good on the inside, but the edifying arrangements outside were insufficient. There were 28 names on the books, and only English books were used; The master was 45 years old (a "linen draper" by trade) and received £19 from school pennies. The catechism was taught here of course, but the education was very elementary. (2) The "Long Room" School: This was a private school, and was held in the large room of the Corner House from the year 1829 (the Corner House became a public house opposite Llandybie Church. It was demolished in the 1960s). The building was not praised in the report; there were 21 children on the register, and only English books were used. The master's age was 37, and he said that he had been educated at Winchester, and was a student before starting to keep school at the age of 16. "The Master said he had been educated at Winchester, and made very high pretensions to mathematical and classical learning. The children under his care were extremely ignorant. As to grammar, he said he would not be bothered with it unless the parents would pay 1 shilling a week for each child. The government of the school appears to be maintained entirely by corporal punishment." (3) The Girl's School, Glyn-hir: There are no details given about this school, but Mrs DuBuisson was responsible for it, and this school was kept with distinction until the end of the 19th century. It was held for a while in Bancy-felin near Melin Glyn-hir (the Mill). A Miss Harries was the last mistress of the school, and her mother before her; the children of the Felin were the only boys permitted to attend this school, and that, as a special favour, Mr D.L.Davies (who later owned "The Bon" in Swansea) was the last boy to attend this school. (4) The Cross Inn School (Ammanford): Another private school that was held above the stables of Gellimanwydd chapel (Christian Temple). It opened in 1844, and there were 46 on the books. A student preparing for the ministry was the first teacher. His income from the children's pennies was £30. "This school was conducted on the old system, the scholars were very orderly, but utterly unused to be questioned." (5) Cross Inn (Dame School): Established in 1846: the number on the books was 42. The mistress was 42 years of age, and had been an assistant teacher to her mother before this. The income of this school was £8. "Held in a dwelling house, and conducted on the individual system. A part of the day is devoted to instructing older girls in needlework. Few could read the New Testament even tolerably, and not one was able to answer a question on what they had read." [Note on the infamous "Blue Books", so-called because of the blue covers of the published report: In 1847 a commission (consisting of Anglican Englishmen) to look into the state of Welsh education reported back, in what became known as the "Treachery of the Blue Books". This was a fairly damning indictment but also a very detailed one which recognised the class and religious divides which hampered progress in education in Wales. Unfortunately, it also made some severe generalisations along racial and moral lines which outraged the Nonconformists and led to a further alienation from Anglicanism.]

Gomer Roberts again:

There was another school on the border of the parish at Llwyndyrys, near Glyn-hir, and Mrs DuBuisson was also responsible for this one; in fact, the Glyn-hir family were very active in education in the parish. They did not charge one penny for teaching the children in their schools, and the girls wore a special outfit consisting of a brown cloak with a red border. The Glyn-hir schools were famous for their sewing work, and "Samplers" made at the school could still be seen in old homes in the parish well into the twentieth century. On holidays the girls walked in one crowd to the Parish Church. When leaving school, each girl was given a copy of the bible, and a sewing box.

.... I have information about other schools kept by the Glyn-hir family in the parish. One in the Derwen, Penybanc. A young woman named Ann Edwards was taking care of this school (perhaps she was the one who kept the 'Dame school' at Cross Inn. She was known to have kept a school in a dwelling house in that area). Here again, the education was free, but only one member of each family was accepted as a pupil. Once a year, the children went to Glyn-hir for a feast, and to receive gifts, and they all looked forward to this annual outing.

.... One bard sang a lament to the memory of William DuBuisson of Glyn-hir, and this reveals the sort of respect that had been fostered towards him and his family for their kindness:-Mewn dagrau rwy'n anfon trwy'r gwledydd o'r bron,

Am orchwyl wnaeth angeu ar DuBuisson;

Bu'n dyoddef mawr gystudd poen dirfawr a chur,

Ond dianc wnaeth trwodd, mae'n galled i'r sir.Bu'n hynod ddefnyddiol tra parodd ei daith,

Mewn bydol orchwylion, i weithwyr gael gwaith,

A phlwyf Llandebie mewn galar mawr sy,

A'r gweiniaid yn ochain yn uchel eu cri.Mae cannoedd o fechgyn a merched bach hardd

A gododd i fyny fel egin mewn gardd;

Rhoi ysgol a llyfrau a gwisgoedd i'r gwan,

Rwy'n credu heb ammheu mai mawr fydd ei ran.In tears I send to all the news

Of hapless DuBuisson's demise,

Affliction great and pain he bore

Until he slipped this earthly shore.In worldly terms his loss is grave

Since work to local folk he gave.

Now Llandybie's grief is great,

The poor and weak bemoan his fate.So many boys and girls we know

Like garden buds, he helped to grow.

School, books and clothes were his bequest

And heaven, I'm sure, is where he'll rest.(Translation made for this web site)

Apart from the schools mentioned in the government reports, I can name two other schools in the parish. The "Academy" that was kept in Piode, and the school that was held in Capel Ficer by one Morgan Lake. Little is known about the 'Academy' or 'Seminary' at Piode. Giraldus wrote about it: "Many years ago, an excellent grammar school was carried on here by the late Mr Evans, where a great many gentlemen belonging to this and the adjoining counties were educated". There is also a tradition about it in one of Elwyn's novels: "Wrestling, boxing, and other gymnastic exercises were prominent items on its curriculum, and it owed much of its reputation as a fashionable school to this fact," According to the gravestone of John Evans, Piode, in the parish graveyard, he died in 1840, aged 75 years.

.... Several other private schools are known of in the parish from the memory of residents of Llandybie in the 1930's. Mr William Haye, the parish registrar, kept a school in Capel Hendre House, and before this, Benjamin D. Thomas (afterwards a minister with the Methodists) kept a school in Hendre, and lodged in the house of the Venerable David Morris. At about the same time, the Rev. William Michael kept a school in Saron chapel. A man named Mr Maglway kept a school in Heolddu, and a Wyddel in the same manner in Pen-y-garn. There are also stories about some sort of schools in the Crick (nearly opposite where St David's church, Saron, stands today); Hendre Cottage; Rose and Crown, where a gentlemen called "Evans bach" was master; and Gorsefach. In Penygroes a man with only one leg, named Davies, kept a school in a cottage; In the loft of the chapel there, a school was kept consecutively under the care of Morgan Lake, Rhys Hopkins, and Timothy Richards (afterwards the famous missionary in China). No doubt, these schools were of some benefit in their day, although the masters were of limited attainment.

.... In the parish register we find the names of two schoolmasters, John Harries (a son of his and his wife Nancy was baptised in 1810), and John Morgan "Schoolmaster in the village" being buried in 1833. In an old account book of John Lewis, who was a cobbler in the village from 1822 - 1829, there are references to schools and schoolmasters:

.... "Danl. Jones, Schoolmaster: April 9th, 1823. Price of shoes for his child, 2s.8d. 1826, Mr Evans schoolmaster. Sept 13th. My children sent to school. 1827. Jany. 8 began the 2nd Qr. of Schooling."

(1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present.

Continuing with Gomer Roberts:

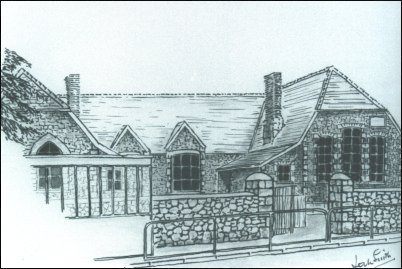

The result of the commission of enquiry in 1843 was the establishing of a day school in the village [Llandybie], and this with the exhortations of the Rev. John Williams the vicar, who stated before the commissioners that they could well support a master in the parish if they had a suitable building to hold the school. They were given land by Earl Cawdor on a lease of 100 years at 1 shilling a year, and the land was transferred to the vicar and his wardens (Thomas Thomas, Cilyrychen, and David Rees Cefncefni) and their successors in the posts. The date of the Deed is June 8th 1848, and in it is stated that the purpose of the school was to educate "children and adults, or children only of the laboring, manufacturing, or other poorer classes in the parish of Llandebie." The school had to be united to the National Society [ie under the control of the church], and open to government supervision, and the religious teaching to be under the care of the vicar. The master and mistress also had to be members of the Church of England. The school was built in 1848; the designer of the building was Sir Gilbert Scott, and the work of constructing the building was given to Mr Richard Bowen.

In a government report (1848-49) there are the following details about Llandybie School:

Llandebie: National: Erection of School and Masters House.

No local endowment.

Total Estimated Expenditure: £672.

Contributions Promised: Private: £208.

From Public Societies: National Society: £100.

Diocesan Board: £20.

Grant awarded: £202.

Provision for 130 Scholars.Here is the report of the Rev. H. Longueville Jones, M.A., the superintendent, in July, 1849:

"The school building has just been completed by aid of a grant of £130 from the Committee of Council: total cost £656. The building is judiciously designed, strongly built, and substantial; the out-premises are large and airy, and plenty of ground for children to play in, besides the master's garden. Recommended some alterations of ventilation which was insufficient; they will be carried out. The desks and forms are all that are wanted for the school to be opened and worked. The building appears to me moderately cheap, considering its dimensions and the great solidity of its walls and timber work.

.... Additional money was given at the end of ten years £350 for various purposes".The "great solidity of its walls and timber work" has served the building well; it still stands on the village square to this day, with its interior converted into use as a church hall, community centre and council chamber in 1971. The building ceased to be used as a school that year when the local education authority introduced the comprehensive system of education to the county. Children over eleven now travel to Tregib Comprehensive in Llandeilo. Llandybie Secondary Modern School (built on the hill next to the gorsedd in 1934) has since 1971 become the primary school for children under eleven. Gomer Roberts continues:

A very interesting book regarding this school is the old 'Log Book' that Griffith Jones began to keep in 1863 — the first year that they had to keep an official record in the school. In this we find sundry notes, not only about the school, but about the village life as well. One can see in it the account of sums of money paid by the Glyn-hir family for the "free scholars", and the names of superintendents and other visitors that came from time to time to the school.

.... Like the rest of the schools of that period, it was a church school at Llandybie, and the teachers were expected to be members of the Church of England, and the schoolmaster was usually the choirmaster and organist of the church. In his novel, "Cynwyn Rhys, Pregethwr", Elwyn gives a few insights to the ecclesiastical aspect, because, although the church had the money and authority, it was not her members who always had the intellectual abilities, and frequently temptation would cause nonconformist young men to forsake their nonconformity in order to obtain a post as teachers, and taking the training path to the college in Carmarthen. The school raised many generations of children, and some of them achieved honour and national fame. The school still held on to its distinction in spite of rumours and talk in the village of having a new school. It was thought at one time that its days were over, but when the new school for children over 11 years was opened in the parish (in 1935), the National school had a new lease of life.

.... Things changed after the Education Act of 1870, with the result that 'The Llandybie United District Board' was formed to administer in the parish, and outside it. Under the authority of this board, a new school was built in Cefneithin in 1894, and a room for the babies was added to Llandybie school. Within a year or so, a babies' class was opened in Pen-y-groes, and a mixed school in Saron.

Ammanford County Primary School on College Street, built in 1870, closed in 1970 and demolished in 1982. (Drawing by WTH Locksmith from 'Ammanford: Origins of Street Names and Notable Historical Records', published by Carmarthenshire County Council in 1999.) In the meantime a new school had been built in Cross Inn (Ammanford). Before this, the only educational facility in this corner of the parish was a school kept in a room above the chapel, and afterwards, a school for babies was kept in a house next door to the "Railway Inn" under the care of Thomas Jones, the sexton. The daughter of Mrs Edwards (who had kept Derwen school, Pen-y-banc) kept a school in a room near Pontamman Mill, but none of these schools flourished. A local council was formed to consider education in the place, and a new school was established under their patronage in Bryn-mawr barn. The secretary of this movement was Mr John Lloyd, Pont-y-clerc (incidentally there was once a school in Pont-y-clerc office), and the name given to this school was "The Brynmawr British School."[ie, a non-church school run by the British and Foreign Society]. Here they were taught to read and write English, a little arithmetic, and some geography and history. The masters here were Mr Harris; Mr John Morris, and Mr Joseph Constantine — during the period of the last named, the new school board came to prominence, and in 1870, they were moved to the new school in Ammanford [this school building was demolished to make way for a Co-op store in 1982].

.... During his time there (in 1896) a school for infants was added to the place. The last elementary school to be built in this populous area was Parc-y-Rhun school, which was opened in 1909 by Lady Dynevor. By this time this area of the parish was part of the 'Ammanford Urban District Council', created in 1903.

A vanished part of Ammanford: The Central Garage (at top), Ammanford Primary School (middle) and the Palace Cinema (bottom). An open-air bus concourse and the Co-operative Stores now stand in their place. Also vanished is the Cross Inn on Ammanford Square (bottom left). The front (boys) and back (girls) school yards are visible in this aerial photograph taken 24th June 1964. Footnote on Gomer Roberts

Gomer Roberts has been quoted from extensively in the foregoing, and the temptation to summarise for the sake of brevity has been resisted. His book 'Hanes Plwyf Llandybie' (History of the Parish of Llandybie) won the 1939 National Eisteddfod History prize, and rightly so. In 1986 he was awarded an honorary D. Litt (Doctor of Literature) by Swansea University. He started his life as a coal miner at about the same time as Amanwy (David Griffiths) and Amanwy's brother Jim Griffiths, and it was Amanwy who helped raise the money to send Gomer Roberts to College in 1923. For more on Gomer Roberts click on 'Gomer Roberts – Historian and Preacher' in the 'People' section of this website.The Journal of William Roberts ('Nefydd') 1853-62

Until a Parliamentary Act in 1902 transferred responsibility for elementary education to local County Councils just about anyone could open and run a school. In practice schools were run either by private individuals or voluntary bodies and the two main voluntary bodies of the nineteenth century were governed by religious interests.The two great voluntary societies for the promotion of elementary education ... the 'British and Foreign School Society' founded in 1808 ... and 'The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church throughout England and Wales', established in 1811, made little headway in Wales during the first thirty years or so of their existence. In a land becoming predominantly nonconformist the British School system, based on Biblical instruction without catechism or particular creed, was more suitable than schools founded specifically to instruct children in the tenets of the Anglican church. The National Society had the advantage of the patronage of the clergy and the upper classes, and, moreover, when government grants and the attendant system of inspection were introduced, the British School movement had to contend with the natural reluctance of dissenters to accept state aid for education. The prejudiced report of the Commissioners on Education in Wales in 1847, published in 1848, did little to commend government inspection in the eyes of Welsh Nonconformists, and for a time strengthened the hands of advocates of the voluntary principle. (E. D. Jones, National Library of Wales Journal, Vol IX/3, Summer 1956.)

These two bodies didn't just sit back and wait for schools to happen but actively undertook missionary work throughout the 19th century to create them, often clashing with each other in the process. One such 'missionary' from the British Society (ie non-conformist religions) was a Baptist Minister, William Roberts, who travelled extensively throughout South Wales to ensure children's education didn't fall into the wrong, ie Church, hands. The draft of the journal of his activities from 1853 to 1862, written for the information of the Society's Committee, is preserved in the National Library of Wales and is a valuable document for the history of elementary education in South Wales. Roberts' diary records several visits to the Amman Valley, including Cross Inn, renamed Ammanford in 1880. Here are the entries for Cross Inn:

August 14 1854

Cross Inn. There is a small school in this place under the Tuition of a Mr Edwards. The room was fitted, and is given gratis by G. Lawford, Esq., for the education of the children of the neighbourhood. It is not a Church school.This G. Lawford was in fact Thomas Lawford, a local gentleman farmer of Carreg Cennen House in Trap, near Llandeilo, who farmed Tirydail House, Dyffryn House and Myddynfych Farm in Cross Inn under lease from the local gentry family, Lord Dynevor of Llandeilo. His generosity didn't last long however as he was declared bankrupt in November 1854, followed by his emigation to Canada in 1855. When William Roberts returnd to Cross Inn two years later things had changed at this school.

September 26 1856, Cross Inn

Cross Inn. This is a very populous neighbourhood, where there is only a Dame School. The schoolmistress (Harriet Edwards) has 70 children in school, pays £4 a year rent for the room, charges 2 pence, 2 1/2 pence& 3 pence per week. The school is not connected with the Church. I have had a conference with some of the inhabitants, and they seemed to think that the prospect of having a good British School established is very promising. I have reason to hope that they will succeed. (E. D. Jones, National Library of Wales Journal. Vol IX/3. Summer 1956.)What the diary doesn't document unfortunately is what the pupils paying 3 pence a week got that the 2 pence pupils didn't. Whatever this was, 70 pupils paying an average of 2.5 pence a week for, say, 40 weeks a year yields £30 a year, not a bad return on the £4 a year rent. A few pieces of coal for heating during the winter months would have been the only other outlay.

William Roberts returned to Cross Inn just a year later:

September 17 1957, Cross Inn

Cross Inn. I had visited this place about 12 months ago. There was then no prospect of establishing any school, excepting a Dame School that was there. At present I was able to form a strong Committee to make a start, and I think that we shall be able to establish a good British School there in a short time. There is a good school-room, the owner will give that free of rent, and he with others will make up about £30 subscriptions towards the salary of a Certified Teacher in addition to the school pence, &c., and will guarantee £60 at once to a Master. But I am to visit the place again in about a month, and to deliver a lecture explanatory of the principles, and Government aid, &c.The non-conformist minister Roberts was forced to make a hasty return to Cross Inn a few months later when he got wind that the Church-controlled National School was trying to install one of their teachers at Cross Inn:

June 29 1858, Cross Inn

Cross Inn. There happened to be a misunderstanding between Mr. Beddoe and his Committee, which was likely to be very injurious to the school, and to lead to Mr. Beddoe's removal. I had an intimation of this and lost no time in visiting the place, and on this evening had an interview with the Committee and Mr. Beddoe. The misunderstanding arose from Mr. Beddoe's intention to take a Pupil Teacher from the National School of Llandybie at the request of the Clergyman, this Clergyman having previously done all he could against establishing the British School, some of the members of the Committee became determined that he should not have the boy recommended by the Clergyman from the National School. Mr. Beddoe on the other hand had expressed himself in very strong terms that they had no business to interfere with him and his Pupil Teacher, and that he would have him in spite of all of them. This had been carried so far that I was afraid at first that the parties could not be reconciled but I have every reason to hope that I settled the matter between them.William Roberts was nothing of not persitant. Within six months he was back in Cross Inn again, worried amongst other things that pupils might defect to the National School:

December 13 1858

Cross Inn. This School was supplied in January last with a Master from Boro Road who came originally from Swansea. But although he was a good Teacher, he did not give the Committee satisfaction, as to his general behaviour, and moral character. This of course led the Committee to express their disapproval of his conduct, and he therefore left the British School and was engaged by the Clergyman to be Master of the National School which is within a mile and a half to the British School. The Committee of this School afterwards received information that J. Roberts, Master of Llangaddock British School would be glad to come to the Cross Inn School. They corresponded with him, and after keeping them long without a decided answer he sent a negative one. They immediately sent to me, requesting a visit, in order to make arrangements about the future. We had a meeting when the above statements were made to me and I advised them.(I) to keep the School open until Xmas and to let the Pupil Teacher do as well as he can, so that any of the children might not follow Mr. Beddow (the late Master) to the National School if possible.

(2) To visit the School alternatively as often as convenient, so that if possible the school would receive a visit of one of the Members of the Committee every day during the management of the Pupil Teacher. I arranged further that Mr. T. Davies of Bangor College should be the future Master of this school.

It wasn't just children who defected either; the teachers engaged at these schools seemed to have been a pretty mercenary lot and would happily leave a British School if a National School offered them more money. Poor William Roberts was back in Cross Inn yet again to try and solve the problem of his teachers being poached by the Church, and then taking their pupils with them:

February 17 1862

Cross Inn. An opposition to the British School in this place is carried on similar to that at Lantarnam. There is a National School in the neighbourhood; they made an offer to the Master of the British School to take the charge of that with more salary. He left, and by his effort and influence many of the children went with him, so that when the Bangor Student that I sent there had only 20 children at first, he sent to inform me all about the case, and I came to try to get the Committee to make an effort to use their influence to get more children to the School. I was glad to find that the number had increased to 32, and that they had prospects for more.Pontamman Chemical Works School, Cross Inn

Another school in Ammanford known at this time was a private concern run by the proprietor of a local chemical works which seems to have survived for about ten years after the opening of Ammanford County Primary School in 1870. This school was established in the 1840s by a Mr. Morris, the proprietor of Pontamman Chemical Works, and the Brodies, who later took over the concern, carried on the school. The pupils at the school seem to have been children of the employees, a sort of creche as well as school, so it would have been quite progressive for the time. The owners of the chemical works also ran a Wesleyan Methodist church in this school building so maybe their motive was control rather than education, with the company regulating just about every aspect of their employees's lives.William Roberts wrote almost contemptuously about this school in his diary:

September 26 1856

Pontamman: There is a small mixed school in this place established by Mr. Morris, proprietor of the chemical works. There are 40 children, but the young woman that is the schoolmistress is not at all adapted to the work. She is the daughter (21 years of age) of the schoolmistress at Cross Inn (Miss Edwards). She only gets off Mr. Morris £10 per annum. It is only the name of a school, and I thought of seeing Mr. Morris, but he was away from home. I will visit again, and urge him to establish a good school.In spite of the Agent's gloomy report, the Pontamman school persisted at least until 1882, and also qualified to receive grants from the Committee of Council. The school was open to all children, and those parents who could afford nothing sent their children free of charge.

Attendance Figures

1877-78 Average attendance 38. Annual Grant £25-18-0.

1880 Accommodation for 57. Average attendance 34. Annual Grant £24-8-0.

1882 Accommodation for 57. Average attendance 50. Annual Grant £34-10-0.(The above is from http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/wal/Roberts4.html)

William Roberts' diary reveals another problem with schools that wasn't due to inter-denominational rivalry; this was the often poor standard of the teachers. As we've seen with Cross Inn's 'Dame School', anyone could set up a school regardless of whether they were qualified or not. This problem was highlighted when Roberts visited a school in nearby Brynamman where the teacher was actually drunk in charge of his class (the italics are in the original diary entry):

March 8 1858, Brynamman (at that time called 'Y Gwter Fawr', ie 'The Big Gutter').

Amman Iron Works. In consequence of receiving information from a friend stating the circumstances of this neighbourhood, and the great want of a good British School now existing, I visited the place to see what could be done there. There is a private school in the place with from 60-70 children in it, and held by a drunken man in a Club room belonging to a public house. I had conversations with several respectable inhabitants, and there is a strong desire to have a good British School established. There is a good building that may be had;---it is an old Independent Chapel 30 x 24 ft [Gibea, Independent/Congregationalist Chapel, Brynaman], held upon a Lease of 999 years, only 15 of which are expired. This may make a good schoolroom. The population is chiefly made up of Colliers connected with the various Coal Works in the place. The population is about 800 or 900. It is supposed that if they could have a good school established there that the scholars would number from 100 to 150. We formed a Committee and I gave them all the requisite information in their present stage of procedure, and I promised to visit them again in April.Other reports about the quality of teachers in Brynamman back up William Roberts' sour opinion. Brynamman-born Watcyn Wyn (1844-1905) was an eminent educator from Brynamman who is quoted as saying this about his village's teachers:

The quality of the schoolteachers varied greatly. One was a butcher and another an old soldier, who, according to Watcyn Wyn, had given up on killing the enemy and was now half-killing the children. But Henry Jones was also a teacher in Brynaman. Later, as Sir Henry Jones, he became well known as a philosopher and was given the chair of the subject at Glasgow University. (W. J. Phillips in Cwm Aman, from Cyfres y Cymoedd (Series of the Valleys), edited by Hywel Teifi Edwards.)

Note on the Diary of William Roberts

This diary was published in full by the National Library of Wales Journal between 1953 and 1958 and has recently been placed on the internet. The full transcripts made by E. D. Jones can be found by clicking on: The Journal of William Roberts ('Nefydd'), 1853-62.This chaotic situation persisted for another 40 years until the state finally intervened. Until then, children's education was used as a football to be kicked around by competing religious interests. The 1902 Education Act abolished the School Boards, and County Council Education Committees were given responsibility for elementary schools, finally bringing some order to this anarchy. This Act also brought accountability into school affairs in the form of democratically elected County Councils, themselves a fairly recent development, and was a belated recognition that education is far too important to be left to religion.

(1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary. (5) School leaving ages — a summary

Year Comments 1880 For the first time, the school leaving age is made compulsory. Before this children might be sent to work as young as six years of age. 1891 Elementary education becomes free of charge 1893 . 1899 . 1902 . 1902 Education Act abolished the School Boards and County Council Education Committees were given responsibility for elementary schools. 1918 . 1944 The 'Butler' Education Act OF 1944 made secondary education free for all and is implemented by the Labour government elected in 1945. 1969 . 2008 Introduced from September 2008

Sources: — History of Wales, John Davies, Dent (1990). — The Foundations of Modern Wales 1642-1780, Geraint H Jenkins, Clarendon Press, University of Wales Press, 1987. — Hanes Plwyf Llandybie (History of the Parish of Llandybie) by Gomer Roberts, published 1939 (in Welsh) translated by Ivor Griffiths (1986). — Ammanford: Origins of Street Names and Notable Historical Records, WTH Locksmith, published by Carmarthenshire County Council in 1999. — The Journal of William Roberts ('Nefydd'), 1853-62. William Roberts, a Baptist Minister at Blaina, Monmouthshire, was in 1853 appointed agent in South Wales for the British and Foreign School Society. The draft of the journal of his activities, written for the information of the Society's Committee from 1853 to 1862 is preserved in the National Library of Wales. It is a valuable document for the development of elementary education in South Wales and includes several visits to Cross Inn (Ammanford) to inspect schools in the locality.

FURTHER READING

The provision of education in the Llandybie, Ammanford and Betws area has a long history, going back at least 270 years from the first circulating schools of Griffith Jones in 1731. This history is too long and detailed to be encompassed by one essay alone so it has had to be divided into several sections. And even this does scant justice to the rich and complex subject matter. It awaits a far more competent historian than the present author and will have to be much more scholarly than this patchwork quilt of a web site will allow. Still, we can but try. The various sections are:Education in Ammanford 1

Education in Ammanford 2

Amman Valley Grammar School from 1914 to the present

Amman Valley Grammar School – the beginnings

Betws Primary School

Ammanford Technical College

Gwynfryn College ('Watcyn Wyn's School')

CONTENTS (1) Introduction. (2) The Circulating Schools. (3) The Sunday School and the Private School. (4) Education from 1843 to the Present. (5) School leaving ages — a summary.