AMMANFORD TECHNICAL COLLEGE

CHAPTER ONE

Events leading to the formation of the College

Elsewhere in this web site we've seen the attempts of people in our area to establish schools for themselves and their children. Despite the tremendous determination and ingenuity they put into the task, and the huge obstacles they overcame in the process, it was only until the state got involved from the late nineteenth century onwards that schools started to become a permanent feature of our towns and villages. But at the start, the only help the state gave was in the

form of limited grant aid to church-run schools, with no further assistance from the state. A network of permanent, local authority-run and funded primary and secondary schools became a reality only from the early years of the twentieth century.

These primary and secondary schools, once established by the state, provided only an academic education and then only for children. It soon became clear, however, that there was no provision, either for those who wished to acquire technical skills and qualifications, or for those whose family circumstances forced them to leave school early.

Even when the state took responsibility for the education of children, it still excluded adults who'd been forced to leave school to bring in much needed money to their impoverished households. The story of Ammanford Technical College is the story of the process to establish first a school where colliery managers and underground officials could acquire necessary mining safety licences, and later a college offering a wider technical education for adults, and some children, from outside the mining industry.

Here are the words of one of those early students of 1927, Elwyn Thomas, written in 1977, by when he'd become the Reverend Elwyn Thomas:

The establishment of a Technical Institute in Ammanford in 1927 was to me, and many others, a day of salvation. Apart from a very few, the great majority of boys graduated naturally from the local council school to the nearest colliery. In many cases boys who had passed the scholarship examination to the County School were unable to implement their success because of adverse circumstances within the home. Silicosis was rampant in the western anthracite coalfield, and although much research was made into the disease, it had not yet been given a name, neither was it accepted as an industrial disease, which called for compensation. This scourge dealt harsh blows to miners homes and affected the economy of the family for a lifetime. It also affected directly the educational and cultural life of the community. The fact that one boy was a pupil following higher education, and that the boy next door was working underground, was no indication that the former was more intelligent than the latter. Often the reverse was the case ...

….. Through my widowed mother's sacrifice and Tom Roberts' [the first principal] untiring devotion to his work and to his pupils, I was able to embark on a University career that seemed a few years before to be nothing more than a dream and a phantom. It is with great delight and gratitude that I always think of Tom Roberts, God bless him.(see below Appendix 2).

We shall tell the story of Ammanford Technical Institute presently, and in some detail, but what, if anything, was available until the opening of this establishment on April 10th 1929? We shall enlist the Reverend Elwyn Thomas as our guide once more:

"[Until] this time there were evening classes in a variety of subjects. These classes were quite popular, and often well attended. The same teacher would conduct two or three classes a week in the winter time, and would be doing this year after year. Often-times the boys looked upon the classes as a means of getting together and as a pastime, it was neither good nor bad. The pattern of many a local evening class was this – the pupils came every winter to support the teacher, who invariably lived in their midst, and canvassing for pupils was a common thing. It was quite natural for a young teacher to be anxious to supplement his income by taking evening classes, but unfortunately his prime purpose in doing so would be financial and personal, with the welfare of the pupils a secondary matter. Any pupil who had any ideas of furthering his education was immediately suspect, and sometimes victimised, and looked upon by the teacher and his fellow students as one whose presence would be unwelcome the following winter. Many such pupils embarked on correspondence courses, and succeeded. Others, in the absence of a teacher, and frustrated by the impersonal nature of correspondence courses, gave up all hope of higher education, but remained useful members of society in industry, religion and civic life.

It was to remedy this situation, brought about by the stagnant character of many local evening classes, that the Ammanford Technical Institute gave a new hope to many. At least the Institute had a curriculum, and it was possible to progress from one grade to another in a variety of subjects. A student who knew of the former frustrations felt that now he was on the move."

(See below Appendix 2)

Today Ammanford Technical College in Dyffryn Road is an impressive, well designed and ideally located building, but its pleasant, tranquil appearance belies its industrial origins. After its beginnings as an annual Summer School in 1919 it soon became a full-time Mining and Technical Institute by 1927 (later to incorporate a Secondary Technical School in 1942), before becoming a fully-fledged Technical College offering a wide variety of courses, both vocational and non-vocational.

Throughout its development, both the location of the college and its buildings have changed considerably. A corrugated zinc shed (part of the old County School in Tirydail) gave way to a section of the old YMCA building (Young Men's Christian Association) in Iscennen Road, with the whole building evantually being taken over. This in turn was superseded in 1955 by the present establishment at Dyffryn Road, Tirydail.

So what factors contributed to the growth of this College? The anthracite mining industry in the Gwendraeth, Amman and Neath Valleys had grown rapidly during the last decade of the nineteenth and the first decade of the twentieth century as the result of a massive increase in the demand, from home and overseas markets, for this virtually smokeless fuel. Promise of wealth and social position drew speculative coal owners to settle in the Ammanford district. In the wake of these followed the manpower necessary to work in the mines. This was made up mainly of displaced agricultural workers resulting from the decline in the farming industry during the latter part of the nineteenth century.

As the demand for anthracite continued to increase, the mining villages grew in size, and the number of pits multiplied. They were sunk to greater depths resulting in an increase in geological, technological social and – above all – human problems.

Conscious of the ever increasing accident rates throughout the coalfields of Britain, which suggested a greater need for expertise in the handling of explosives and a more advanced knowledge of surveying, the Government passed the Coal Mines Act of 1911 which appointed "A Board for Mining Examinations" constituted by the Secretary of State, to examine and issue Certificates of Competency to Colliery Managers, Under-Managers and Firemen (see Appendix 4).

The intervention of the First World War restricted the full implementation of this Act and it was not until the early twenties that really effective measures were taken to fulfil its requirements, particularly those relating to certificates of competency for Firemen. (A 'Fireman' is the person responsible for safety underground. These responsibilities include monitoring the build-up of flammable gases such as methane, or "fire-damp", whose explosions result in fires underground, so he acquired the name of 'Fireman', not to confused with the fire brigade personnel of the same name).

It was to cater for this latter group of workmen that evening classes were held in the village elementary schools in the area. The instruction was mainly in preparation for the statutory firemen's examination, the instructors being officials of local collieries who had already obtained their First and Second Class Certificates of Competency as mining engineers.

In the early twenties, supplementary courses in the form of an Annual Summer School were held in a corrugated iron zinc shed in Tirydail and later at the Amman Valley Grammar School (then known as the Amman Valley County School). The fertile response of those students towards education can be understood easily when the background to the mining conditions of the period is considered. Fatal accidents were frequent and working conditions virtually intolerable. (See Appendix 1).

Facilities for training mining officials were proving inadequate so the then Carmarthenshire County Council decided to appoint a Mining Committee to investigate the resources available to extend the further educational needs of local miners with the availability of a £4,350 grant from the Miners' Welfare Fund, to be used for the education of Carmarthenshire miners. A fund of £5 million was available nationally from a levy of 1 pence (pre-decimalisation) per ton on the output of all coal in Great Britain for a period of five years. The amount set apart for the education of miners in the whole of Great Britain was about £475,000. This money was divided among the coalfields according to the numbers of resident miners in each coalfield. £90,000 was the estimated sum for the South Wales and Monmouthshire Coalfield. A proportion was to be applied to University Education, leaving about £72,000 for distribution to the Education Authorities for developing facilities for the education of the miners in the area. Carmarthenshire's share of the £72,000 was approximately £4,350.

On the 9th June. 1927, with the approval of the Education Committee, a Senior Centre, to be located at Ammanford had been proposed; a site (The YMCA building in Iscennen Road) chosen; Architect's recommendation approved; the District Valuer's valuation made; and the Education Committee were then in a position to resolve that the portion of the YMCA hostel required for the new Mining Institute be purchased, as freehold, for £2,750. The YMCA (Young Men's Christian Association) had been built in 1910 and offered hostel accommodation and a range of leisure and entertainment for the youth, presumably Christian, of the area. Even though if offered billiard tables, a swimming pool, reading room and hostel accomodation amongst its facilities, by the 1920s its time had passed and it had to be sold off.

As the Y.M.C.A. building was not ready the courses were held initially at the Amman Valley County School in Tirydail, the corrugated iron building mentioned above. The recommended fee for Senior Course Students was five shillings.

The commencement of the Senior Courses in mining was soon followed by the opening of the Mining and Technical Institute at the YMCA building on April 10th 1929. It was reported in the "Western Mail and South Wales News" an account of which reads as follows:

£6,000 INSTITUTE

FOR MINING STUDENTSAMMANFORD CENTRE FOR SENIOR COURSES

A Mining and Technical Institute to serve the South-Eastern portion of industrial Carmarthenshire was opened at Ammanford on Wednesday, April 10th, 1929. The Institute is the first of its kind in the county and marks a big step forward in the facilities for education on the technical side.

It is housed in the former YMCA buildings, which have been extensively altered for the purpose and equipped on modern lines.

There are two lecture-rooms, drawing, physics and electrical rooms, chemistry laboratory, ventilation room equipped with Waddle fan and air duct, staff rooms, etc., and the equipment throughout leaves little to be desired on the part of the students who will receive here a senior course of technical training in preparation for more advanced study at Swansea Technical College and elsewhere.

CHAPTER TWO – CHANGES

1929–1939

By 1929, the S1 and senior second year (S2) courses included mathematics, engineering drawing, physics, and English. Some students did so well in the S2 examination that they were encouraged to consider embarking on a University course. To enable them to do so a course leading to the Matriculation examination (the equivalent of the modern 'A' levels) of the University of London was introduced. This was an academic course attended mostly by working miners, who were released from work on two days a week (without pay) for two years. They were re-imbursed at the rate of 8 shillings per day plus travelling expenses by the local authority but only after being searchingly interviewed and tested by the Clerk to the County Council (an experienced miner could expect to earn 12 shillings a day, so this was a considerable sacrifice). A description of the 'searching' interview has been left us by one of the first ever students to take the university entrance course at the Technical Institute:We, the successful students, were asked to appear at the Education Offices in Carmarthen to meet the secretary to the Committee, Mr. Nicholas (or Nicholas Caerfyrddin as he was known). We travelled to Carmarthen after our day's work at our respective mines and answered many questions and recited our favourite twenty lines from Shakespeare at our interview. We were given to understand that a matriculation class was to materialise and that suitable teachers would be found for us.

...... This possibly was the first day release class ever to be held in Carmarthenshire. We were to attend on Mondays and Tuesdays of each week morning, afternoon and evening sessions on Mondays; mornings and afternoons on Tuesdays. Furthermore we were to be re-imbursed to the extent of eight shillings a day for loss of wages for these days by the Education Committee.

...... By that time, I had been employed for eight years, since I had left school at fourteen, at the Emlyn Colliery, Penygroes. As a piece worker at the coalface, I could earn, perhaps, on average twelve shillings a day. The "minimum wage" at that time was eight shillings per day." (Note: for those who have grown up since the decimalisation of our coinage in 1971, a shilling equals five pence; eight shillings equals 40 pence and twelve shillings equals 60 pence)(Bryn Banfield in 1929 – see Appendix 3 below)

"Our favourite twenty lines from Shakespeare" – we'll not see those days again.

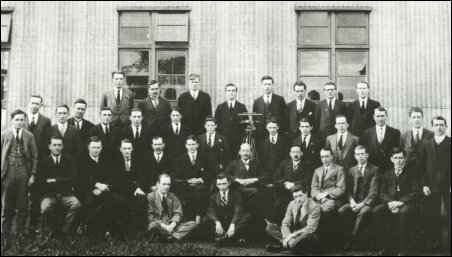

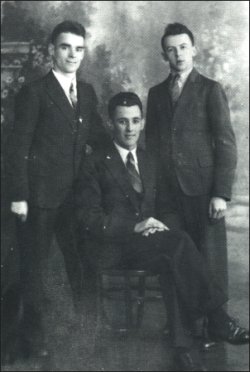

1932 – The first three students to achieve University entrance qualifications at Ammanford Technical College The success of these first four matriculation students heralded many more successes and the matriculation course became an accepted feature of the Institute's curriculum. It provided a launching platform for many a successful academic career.

Although other courses soon received day release from the mine owners, and some even had partial wages for the time off from work, the mine owners were reluctant to release students who might go onto university and thus be lost to the industry. They were quite happy, however, to let the tax payer, in the form of a local council grant, contribute 8 shillings a day to the training of these employees who then acquired greatly improved skills and qualifications at no expense to themselves. It was not until the session 1943-44 the college was able to obtain day release facilities for the P2, S1 and S2 mining courses with payment at the rate of 8 shillings per one day a week attendance.

The Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries Ltd., and the Brynhenllys Colliery, Cwmtwrch, were the first to give day release for further education with a partial repayment of wages. Mr. R. W. Burgess (General Manager of Amalgamated Anthracite Ltd.) intimated in the discussion which led to these payments, that no payments would be made to students following matriculation courses. Matriculation success usually resulted in the student being lured away from the coal industry, whereas those who attended courses leading to the S3 certificate proceeded to Swansea for full certificates and then continued their careers in the coal industry.

By 1938 the college included courses for colliery managers, colliery electricians and mechanics, courses for juveniles in the mining industry and courses in building and allied trades were also offered.

1939–1945

The outbreak of the war with Germany in 1939 plunged Britain into a period of frenzied activity. Many men were, of necessity, conscripted to the armed forces leaving the men at home employed in producing power, steel, armaments, and food. Wherever possible, labour was supplemented by women. Men over the age of 18 years employed in the mines were generally exempted from recruitment to the armed forces under the provisions of the Essential Works Order. Course at the technical College were changed to assist the war effort, such as mathematics classes for potential RAF air crews. As part of the war effort the caretaker's house attached to the building and the YMCA's old swimming pool were taken over..The sudden fall in the demand for coal following the collapse of France resulted in a number of mines being made temporarily idle and many men working irregularly over the latter part of 1940 and the early months of 1941. Over this period manpower migration accelerated to reach a peak. Only a small proportion of miners who had left returned when the demand for coal was restored. Some of the mines made idle in 1940 had not reopened by 1946, owing to lack of manpower.

The decline in manpower was, however, arrested when in May 1941 the first Essential Work (Coalmining Industry) Order came into operation. The Order provided, among other things, that the employment of a man engaged in coalmining could not be terminated by his employer or by himself without the permission of a National Service Officer of the Ministry of Labour. Abnormal recruitment of ex-miners included the compulsory registration of all men who had left the industry in January 1935 and this compulsory regisration led to the return of some 30,000 ex-miners to the war-time mines throughout Britain. Despite these emergency measures the numbers attending the college plummeted during the war.

One new course was however introduced and that was In 1942 when the Junior Technical School was established at the Institute. It provided a three year full-time course for secondary school children, entry into the course being by examination with a minimum age requirement of l3½. This course ceased in 1962 but Amman Valley Secondary Modern School incorporated it into its syllabus for a while.

Opera singer Delme Bryn Jones "discordant"

One of these students – Delme Bryn Jones from Brynamman – went on to become an internationally famous opera singer. It is rather ironic to recall that he was asked to refrain from singing in assembly as his voice was judged to be rather discordant! A competent rugby player, he was awarded a Welsh Youth Rugby Cap whilst at the College.Throughout this period local miners continued to attend the courses for Colliery Managers, Mine Chargemen and Firemen, held at the Ammanford Mining and Technical Institute.

After 1945

With the implementation of the Education Act of 1944 and free secondary education, the concept of day release for students to attend Technical Colleges came to be accepted, even though some coal companies remained reluctant to contribute financially, especially to aid those students who wished to pursue the matriculation course.1947 and Nationalisation of the mines

An historic landmark in the history of British coal mining occurred on the 1st January, 1947, when the industry was nationalised and ownership vested in a new public body – The National Coal Board (N.C.B.). The South Wales coalfield became the South Western Division of the Board and was divided into nine administrative areas controlling 329 collieries producing 21 million tons per annum. Now, at last, day release from the mines was with full pay. (Wales now has only one colliery – Tower colliery near Aberdare. The last coal mine in the Amman Valley, Betws Colliery, was closed in June 2003).Courses for apprentices in motor engineering on a day-release basis were started in 1948 and which were the first of their kind in Carmarthenshire.

In 1949, classes in commercial subjects were started in the old College building. The classes were set up with the object of promoting further education for students engaged in work of a commercial nature and were held in the evenings where bookkeeping, commerce, shorthand and English were taught.

The use of the old swimming pool and workshop, started during the war, continued after 1946. Towards the end of the 1940s, single subject courses offered at the Institute included oxy-acetylene welding, fitting and turning, and cabinet making. One problem not anticipated was the slope of the swimming pool where much of the equipment was housed. Tools, which escaped along the inclined 'swimming pool' workshop floor had regularly to be retrieved although the slope could also prove useful in sliding tools and materials down to the 'deep' end! A student at the time remembers the working conditions:

The workshop was inside an old swimming pool and as we all know, the bottom of a swimming pool slopes. Woodwork was being carried on in the shallow end whilst metal work was being taught in the deep end and if one wanted a piece of wood from the woodwork department it was quite a climb to go and get it from the woodwork bench. A few trips to the woodwork bench was exhausting. (D J Bevan)

In September. 1949, the Ammanford Mining and Technical Institute became known as the Ammanford Technical College which included the Ammanford Secondary Technical School. The College, which had begun with the primary intention of increasing the skills of the miners, had thus expanded to include the education of adults in subjects far removed from mining, the education of youths over 13½ years, and the education of girls for nursing and secretarial careers.

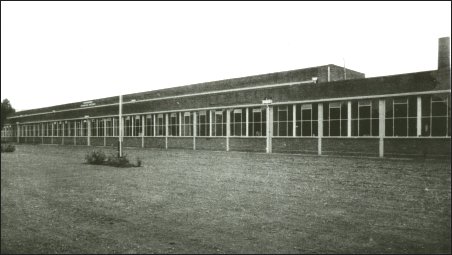

1955–The New College

Ammanford Technical College can finally have been said to have left its industrial origins in 1955 with the move to a large and purpose built campus in Dyffryn Road, Tirydail, at a cost of £180,000. Although it continued to offer education to those employed in, or having connections, with the mining industry, by now the courses on offer were radically removed from mining. As well as an expansion in the commercial courses started in the old YMCA buildings, with many students now coming from the Grammar School, a pre-nursing course was added leading to entry to a full nursing course. By 1957 another £45,000 was spent on additional facilities. In the 1960s a course to train Nursery Nurses (NNEB) was added as was a course to train residential care staff in 1971 and from 1973 the training of District Nurses appeared on the syllabus.

The college now had so many students it had its own cricket and rugby teams. It had its own canteen, where before students in the old YMCA building had only the local fish and chip shop in Quay Street, now a supermarket. An assembly hall was added in 1965 and in 1966 a new course for first year apprentices at local engineering firms was introduced.

1985 – Carmarthenshire College of Technology and Arts (the CCTA)

The Carmarthenshire College of Technology and the Arts (the CCTA) came into being in 1985 following the merger of individual colleges at Ammanford, Llanelli, Carmarthen and Gelli Aur Agricultural College, Llandeilo. They now deliver a wide range of further education and higher education courses from the five campuses: Pibwr Lwyd and Job's Well (Carmarthen), the Graig (Llanelli), Ammanford, and Gelli Aur (Golden Grove) Agricultural College near Llandeilo.In addition to the five campuses the college supports a further four premises: two farms and two town-centre premises. The college draws its students from rural and semi-urban regions including the industrial town of Llanelli and the Amman valley though a significant number of higher education students come from further afield. The courses run cover a wide range of disciplines – the sciences, technology, business, law, computing, catering, building, languages and the arts.

COURSE SUMMARY

GCSE/A/AS Levels

General Education

Access to Further and Higher Education

Hairdressing and Beauty

Art and Design

Land-based Studies

Applied Science

Secretarial and Office Technology

Business/Management

Tourism and Leisure

Catering

Independent Living Skills

Caring and Health

Computing and Information Technology

Adult-based Education and English for Speakers of Other Languages

Construction

Welsh for Adults

Engineering

Non-Schedule 2 provisionFrom its modest beginnings in 1919 with a dozen or so colliery managers and safety officials attending a summer school, Ammanford Technical College has now mutated into one of six campuses of the CCTA which now has almost 2,500 full time students and 10,000 part time students. In 1934 there were just 62 students – 14 part-time day students and 48 evening students. In 1977 this had risen to a total of 674. The CCTA now offers the widest possible range of courses, some a legacy of the old technical colleges while others are more recent and couldn't even have been imagined in those far-off days. The CCTA now offers part-time and full-time degree courses, spread over their six campuses, in the following categories:

Degree Courses

Art, Design & Performance;

Business, Management & Office Technology;

Computing & Applied Science;

Engineering & Construction;

Health, Social & Child Care;

Sport, Leisure, Tourism & Landbased Studies

. November 1998 November 1999 Full-time 2,217 2,364 Part-time 9,460 8,245 Block Release 64 40 Open and Distance Learning 2,320 2,454 Totals 14,061 13,116 Postscript – the YMCA building

The old YMCA building underwent a succession of uses after the transfer of the Technical College to Dyffryn Road in 1955. For a while it lay unused except as a storeroom for library books from the County branch library which was housed in a rented building in College Street. Then in 1964 one of the large rooms in the YMCA building was used to relocate and expand Ammanford branch library until 1977 when the old 'swimming pool' annexe was demolished and the area filled in. A prefabricated single story structure was built to house a new, much bigger, branch library until a custom built premise was built on Ammanford Square in 1999. In November 2001 the prefabricated library building was demolished. The front of the YMCA still stands and the old caretaker's accommodation at the back was converted for use as an adult education centre called the Cennen Centre in the 1980s. The rest of the building is now part of the County Council's Social Services.Note: Much of the above has been summarised from 'Coleg Technegol Rhydaman (Ammanford Technical College), 1927-1977', published by Dyfed County Council in 1977 as part of the fiftieth anniversary celebrations of the college. There were several Appendices to the booklet written by former students at the college in its early days. We include the ones below, which offer a fascinating glimpse into the long-lost past, as well as reminding us that what we take for granted today – education – had to fought for against tremendous odds by our parents and grandparents.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX 1

Coal Mining in the Thirties

My memory frequently goes back to the days when I left school and took my first job. After many weeks of fruitless searching I at last obtained employment at the Pembrey Collieries Ltd., known locally as "Y Ffrwd" (the Stream, or Torrent).

...... One was lucky indeed to find work at all and I was privileged to have been taken on as a boy collier, called a "Carter". I shall explain later the meaning of this term.

...... The Colliery was comparatively small, employing some 350 men and boys. The methods used for getting coal were more or less the same as had been used for the past century. There was little in the way of machinery other than the winding engine, which was used to haul the coal to the surface.

...... It was a happy place to work. The collier is renowned for his sense of humour and loyalty.

...... I believe I can recollect the first day I went to work. I got up at about 5.30 a.m. and dressed in my working clothes and left home to catch the workmen's bus. It seems incredible now, but this vehicle was a double-decker fitted with solid tyres which creaked and groaned its way along, causing all my young bones to vibrate. The men were quietly chatting in small groups and smoking before the arrival of our transport then filed solemnly into the 'bus'.

...... On arrival at the colliery surface the men alighted and made their way to the drift entrance and to the lamp room to collect their safety lamps. A token bearing their work number was handed in and a lamp handed to them. This also bore the same number. This process was reversed at the end of the day. The lamp was their responsibility and any misuse or damage would bring down the wrath of the lamp man. The lamps were cleaned and refilled with oil, and wicks were trimmed ready for the next day.

...... The "Ffrwd" was a drift mine. This means that it was a gradual slope into the bowels of the earth, not a direct descent as in a pit. Men were conveyed on a carriage called a "Spake", a contraption made by fixing a wooden frame upon tram wheels and axles. A bar was fitted along the centre and one man sat on each side. Eight men were carried on each vehicle. There were about eight vehicles to a journey.

...... The ritual before getting onto the "Spake" was that everyone made sure that he carried no tobacco or matches. Cigarettes were put into a small tin and hidden on the "Bank" ready for a smoke on return to the surface. These were occasionally pilfered, but it was seldom that your last cigarette was taken, and anyone caught doing so would be ostracised by his mates.

...... We boarded the "Spake" and I entered the mine for the first time. Travelling downwards at just above walking pace we clattered our way along the metal rail into the gloom and now the lamp was our only means of light. It was surprisingly good. It is difficult to describe the total darkness of the coal mine, not a silhouette, not a glimmer of light from anywhere.

...... On reaching the heading the "Spake" stopped to allow the men of that area to alight, and the rest of the journey was on foot. We stumbled along the sleepered track for about half a mile and at this stage I branched off with my collier and others to my heading which was reached by climbing an incline and so on to my "top hole".

...... The "tophole" was a tunnel driven upwards on the rise side of the heading until it 'reached through to the heading above, usually a distance of about 100 yards. The collier commenced to dig upwards at an angle into the coal seam. At this stage the coal was loaded directly into the tram and my job was comparatively easy for the first few days. As the work progressed, however, the hand cart came into operation. The cart had no wheels but was moved like a sledge.

...... When the "tophole" had progressed forward the collier had to cut out a "stage" upon which the coal could be stacked in such a position that the trammer could fill his vehicle. This was done by cutting into the rock beneath the entrance to the tophole and lining the floor with wooden planks. A metal rail was placed across the top so that the cart could be turned sideways and the contents tipped onto the stage. When this was completed the scene was set for serious coal getting.

...... As the distance from the "Stage" to the coal face increased and became too far to shovel the coal in two "throws", the hand cart was brought into use. It was made of wood, oblong in shape and being without wheels it moved on skids just like a sledge. It could hold between four and five hundredweight of coal, depending on the skill of the "Carter" in loading. On each end was fitted a "U" bolt to which could be attached a chain used by the Carter for dragging the vehicle. A form of harness, known as a "dress", was made by cutting a tyre into a sufficient length to fit around the boy's waist. Around this was passed a strong metal chain hooked in front and passed between the boy's legs and hooked to the "U" bolt of the cart. The boy then crawled along the slope up to the coal face dragging the cart behind him. He loaded the cart with coal, then hitched the hook to the front of the cart and dragged it down to the stage and unloaded the coal. It was possible for a good boy to claim between 10 – 20 carts of coal each shift, depending on the length of the tophole.

...... After moving upwards about 10 yards a "Crossing" was made to the right of the tophole to meet the collier on the other side. This was done at regular intervals in order to facilitate the circulation of air through the workings. After passing the first crossing it was decided to bring two carts into operation. A post was fitted in the centre of the roadway just below the coal face and a pulley attached to the post through which was passed a chain, the ends of which were attached to both carts.

...... The full cart was dragged downwards, pulling the empty 'vehicle up at the same time.

...... The basic wage of the boy was 19 shillings per week, but piece rate payment was made for coal handled by him. The rate started at 4½ d per ton increasing to a maximum of 10½ d. depending upon the distance of the face from the Stage.

...... It was hard work as the boy heaved and sweated in the confined space. A height of 3 ft. was considered to be good, frequently it was about 2 ft. 6 ins. The carter had to handle his heavy cart and at the same time carry his safety lamp and ensure that it did not go out. Often the slightest tap on the base of the lamp was enough to extinguish it. The lamp was locked and even if one had a match to light it, it would not be possible. The only solution was to re-trace your steps to the 'parting" at the drift and use the "relighting machine". If the collier was ahead with his coal hewing he would lend his lamp amid threats as to what would happen if the incident was repeated. On some occasions the unfortunate boy had to grope his way down the incline, along the lower heading and on to the parting in total darkness. If you have never experienced it. It is difficult to imagine complete and utter darkness. One handled one's lamp very carefully. If the tophole was not too far advanced it was possible to leave the lamp hanging on a prop near the stage and make use of the collier's lamp to light the cart filling process. In the main, however, the lamp had to he carried on the belt around the waist and swung expertly between the legs as one walked to avoid bruising inside the knees by striking with the heavy brass base of the lamp. Herein lay the danger of losing the flame if you slipped and the base of the lamp struck the ground sharply.

...... Another difficulty encountered by the new boy was avoiding striking his back against the "collars", crosspieces of timber used to support the roof at what was considered to be a weak point. I bear the scars of many an early encounter with the supports. Having previously received a cut. I found that a second contact, however slight, would knock the scab off the wound with sickening results. So one learned to be careful.

...... When the tophole reached through to the heading above, the next step was to take coal out from the pillars between the topholes and the crossings. The collier then had a fairly easy task as the coal rolled out if struck at the correct angle. Most of these pillars of coal were removed leaving large expanses of roof supported only by wooden pit props.

...... The coal hewer was a man of great skill obtained over many years of working at the coal face. He was able to look at the "face" and decide which side to work first in order to loosen the coal. His tools consisted of man-drills of various types, a sledge hammer and metal wedges, and an axe. The mandrills and axe were carefully sharpened and protected. He would not allow any unskilled person to use them. The boy's job was to take them up to the surface blacksmith for sharpening, but he would invariably collect them himself in case they were blunted by an irresponsible youth.

...... Hard work and coal dust frequently made these men appear older than their years although many worked on until 65 or 70 years of age. The skill and care with which he worked was a joy to see and many an elderly man who could hardly scramble to his place of work could far exceed the coal output of the younger, stronger and less experienced collier. The majority were men of great integrity and wisdom. It was a pleasure to work with them and I admired them very much. Little was said at that time about the dread disease of silicosis caused by rock and coal dust, but looking back I realise that many of them suffered grievously from it. The scramble up the incline, so easy for us, was interspersed with frequent rests while they wheezed and coughed. However, when he reached his domain he was king and no one would have the temerity to tell him how to do his job. His face was scarred with blue marks of many cuts and his hands calloused by the pick and shovel. He was frequently a "rough diamond" hut a true diamond he was amongst men.

...... The intermediate step between the collier and the Carter was the man who loaded the coal from the stage and pushed it to the point where the pit pony could collect several loaded trains and haul them out to the parting where they were hitched to the main rope and conveyed to the surface. These men were the young strong adults of the mine. No job this for the weak. The trains were made of heavy steel plate and even empty were difficult to push along the uneven rails. The load could be between I ton and 25 hundredweights. I have seen some of these hefty young men pushing two at a time and controlling them with great skill. The "Trammers" as they were known, had a longer shovel and the speed with which they loaded their vehicle was a source of pride and argument amongst them.

...... At the incline, which worked on the same principle as the two carts, the full tram was pushed over and a brake lever was used to slow the descent to a reasonable speed. At the foot of the incline was a man known as a "Hitcher" whose job was to attach the empty tram to one end of the rope and signal the trammer at the top when he was ready to receive the full tram. Alongside the incline was fitted a hollow pipe through which they called to each other. There were occasions when they misunderstood each other's instructions and a full tram thundered down before the empty one was hitched to the rope, with dire results. On receiving the full tram at the bottom of the incline the hitcher would shunt it to a small parting to make up a journey of about eight trains ready to be drawn out to the drift by a pit pony.

...... The person in charge of the pit pony was known as the "Haulier". His duty was to collect the empty trains at the drift and convey them into the headings to the point nearest to the coal face, and to collect the full vehicles and take them out to the drift, where they were marshalled into a journey bound for the surface. The hauliers were responsible for the welfare of their ponies and looked after them well. At the end of the shift they would return the animals to an underground stable in the care of the stable man. The animals were well looked after, groomed and fed, and were at all times in first class condition. However, they were not often taken to the surface as this meant a long walk up the steep drift as they could not be carried on any vehicle due to the low roof conditions. When the animals did surface after long periods they were temporarily blind, but it was a joy to see them galloping over the fields in the sunshine after their dark and cramped quarters below ground.

...... The worker in charge of the Spake and journeys of coal trains to the surface was called the "Rider". He controlled his trains by bell contact with the winding house on the "Bank". Stretching from the "Winder" to the bottom of the drift was a pair of electrical wires. The man placed a hook on the top wire and made contact with the other wire to form a circuit and ring the bell in the winding house – one ring for stop, two to lower and three to raise.

...... In addition to the man in charge at the winding house there were surface workers to control the journeys and weigh the trains. Each tram was marked in chalk by the trammer, giving the collier's number and the quantity was credited to the collier. If a journey was derailed en route to the surface or any single tram lost part or all its load, it was marked 'Broken' and the collier was credited with the weight of his previous tram.

...... To check the loads at the weigh bridge were two "Check Weighers", one for the Company and one for the men. The men's Check Weigher was often also the "Union man" to whom we paid our Union dues.

...... At the end of the shift, weary and covered in coal dust, we made our way out from the coal face to the drift and waited for the spake to take us to the surface.

...... Friday was pay-day and the older men collected their pay packets and checked the contents against the details on the packet. So many feet of top ripping at so much a foot. So many yards of bottom cut to sustain the height of the roof when pressure caused the floor to rise. Payment for the work was made to the collier and invariably he would meet his Carter later on that evening to give him his remuneration, sometimes with an extra half crown if it had been a good week.

...... This is a brief glimpse of the miner of the 1930's. A hard, tough life, but I doubt whether in any industry, past, present or future, one would ever find such comradeship, loyalty and friendship as that of the old coal miner.Contribution by Ex-Inspector 0.J. Anthony, Dyfed Powys Police.

APPENDIX 2

Rev. Elwyn Thomas

The establishment of a Technical Institute in Ammanford in 1927 was to me, and many others, a day of salvation. Apart from a very few, the great majority of boys graduated naturally from the local council school to the nearest colliery. In many cases boys who had passed the scholarship examination to the County School were unable to implement their success because of adverse circumstances within the home. Silicosis was rampant in the western anthracite coalfield, and although much research was made into the disease, it had not yet been given a name, neither was it accepted as an industrial disease, which called for compensation. This scourge dealt harsh blows to miners homes and affected the economy of the family for a lifetime. It also affected directly the educational and cultural life of the community. The fact that one boy was a pupil following higher education, and that the boy next door was working underground, was no indication that the former was more intelligent than the latter. Often the reverse was the case.

...... At this time there were evening classes in a variety of subjects. These classes were quite popular, and often well attended. The same teacher would conduct two or three classes a week in the winter time, and would be doing this year after year. Oftentimes the boys looked upon the classes as a means of getting together and as a pastime, it was neither good nor bad. The pattern of many a local evening class was this – the pupils came every winter to support the teacher, who invariably lived in their midst, and canvassing for pupils was a common thing. It was quite natural for a young teacher to be anxious to supplement his income by taking evening classes, but unfortunately his prime purpose in doing so would be financial and personal, with the welfare of the pupils a secondary matter. Any pupil who had any ideas of furthering his education was immediately suspect, and sometimes victimised, and looked upon by the teacher and his fellow students as one whose presence would be unwelcome the following winter. Many such pupils embarked on correspondence courses, and succeeded. Others, in the absence of a teacher, and frustrated by the impersonal nature of correspondence courses, gave up all hope of higher education, but remained useful members of society in industry, religion and civic life.

...... It was to remedy this situation, brought about by the stagnant character of many local evening classes, that the Ammanford Technical Institute gave a new hope to many. At least the Institute had a curriculum, and it was possible to progress from one grade to another in a variety of subjects. A student who knew of the former frustrations felt that now he was on the move. So much depends, of course, on the Principal of any Institute and no appointment, could have been more providential than that of Tom Roberts, fresh from University, full of zeal and a man of vision. He was young, and many of his pupils were older than he was. Tom Roberts was anxious to establish himself as a leader of technical education, and to further the gifts of those who were under his tuition. His work was a consuming passion, and he knew nothing of the Welsh word 'maldod', certainly not in his technique of teaching. His sharp word discouraged many a pupil who lacked his conscientiousness, but those who interpreted his sharp, even caustic remarks, at times, as an expression of his concern for his pupils, and as evidence of his vocation, stuck to him like glue and became his life-long friends.

...... Apart from the work done in evening classes, there was an abundance of homework for the evenings without classes, and this absorbed all free time. To be a pupil of Tom Roberts in those days was a complete servitude, but it was a servitude for master and pupil alike. One little example may serve to illustrate his consuming passion about work. One afternoon I was standing in a queue underground on the 5 West Parting of Great Mountain Colliery No. 1 Slant waiting for the spake, at the end of the morning shift. It was custom for the officials to take their place at the head of the queue, and on this particular afternoon a group of officials passed by, including the manager and undermanager and with them Tom Roberts. That was the last place I expected to see him and I blurted out in my excitement "hello Mr. Roberts" He immediately turned his lamp in my direction and without expressing the slightest surprise said "It's you Thomas, have you done your homework?" He was at that time visiting collieries, researching for his Master of Science degree.

...... From evening classes the course blossomed out to occasional day classes as well, and the initial experiment to embark on the London Matriculation Course, employed every minute of the four students earmarked for that marathon. It is with sincere gratitude that I look back upon his labours, his stimulation and example. There is a verse in the scriptures about a person 'who put many on their feet' Tom Roberts was such a one. It is true that my subsequent studies were in the humanities and not in the sciences but Tom Roberts' discipline put me and others on the way and stimulated me to do an honest days work in whatever sphere I found myself in.

...... Through my widowed mother's sacrifice and Tom Roberts' untiring devotion to his work and to his pupils, I was able to embark on a University career that seemed a few years before to be nothing more than a dream and a phantom. It is with great delight and gratitude that I always think of Tom Roberts, God bless him.Rev. Elwyn Thomas, BA., B.D. (1977)

APPENDIX 3

From Mr. Bryn Banfield, one of the earliest students of the Ammanford Technical College

I was in at the beginning. I had been fortunate enough to have attended one of the very few evening classes which had successfully survived a winter session in the area. It was held at Saron Elementary School, and Mr. S. Nicholas, a teacher at the School, took the class.

...... This was in 1928, and I was to attend the S1 evening course at the Ammanford Central School in the autumn. Mr. Tom Roberts, who has since distinguished himself as Principal of the Technical College, was in charge.

...... I was accepted on to a short summer course which Mr. Roberts felt would help the students to keep in touch during the summer months, and so began my studentship which was to last for three and a half years. My first year was a success.

...... By the beginning of the winter courses of 1929, the YMCA building in Iscennen Road, which had been idle for many years, was turned to good use and became the Ammanford Mining and Technical Institute. I was one of the privileged small group of students to attend the first S2 course there. At the end of the year, only four had reached the required standard, namely, D. D. Jones (Cefneithin), Elwyn Thomas (Tumble), and Gwyn Roberts and myself from Penygroes. We were to become the first part-time day students.

...... At the time, there were no further courses planned for the Institute and we might have had to travel to Swansea for our further education. But it was whispered that a matriculation class was a possibility for the autumn.

...... We, the successful students, were asked to appear at the Education Offices in Carmarthen to meet the secretary to the Committee, Mr. Nicholas (or Nicholas Caerfyrddin as he was known). We travelled to Carmarthen after our day's work at our respective mines and answered many questions and recited our favourite twenty lines from Shakespeare at our interview. We were given to understand that a matriculation class was to materialise and that suitable teachers would be found for us.

...... This possibly was the first day release class ever to be held in Carmarthenshire We were to attend on Mondays and Tuesdays of each week morning, afternoon and evening sessions on Mondays; mornings and afternoons on Tuesdays. Furthermore we were to be reimbursed to the extent of eight shillings a day for loss of wages for these days by the Education Committee.

...... By that time, I had been employed for eight years, since I had left school at fourteen, at the Emlyn Colliery, Penygroes. As a piece worker at the coalface, I could earn, perhaps, on average twelve shillings a day. The "minimum wage" at that time was eight shillings per day.

...... The course lasted about fifteen months. Mr. Tom Roberts was to teach us mathematics and science, Rev. Gwilym Owen was to teach Welsh, and Mr. T. V. Shaw, who was later to become the Headmaster of Llanelli Grammar School, travelled by bus from Llanelli each Monday evening to teach us English. We also found that Mr. Tom Roberts was to provide any motivation that might have been necessary and we wondered at the charm and the expertise of Mr. Shaw as a teacher of English. It was all to be a most exhilarating experience to us.

...... From every aspect the experiment seems to have been a success. We were entered for the London University Examination to be set at Cardiff University in January 1932. There were three successes out of four candidates, including two first division passes.

...... Meanwhile, the Institute was growing rapidly. Evening classes were increasing in size and popularity. Mr. Tom Roberts was deservedly appointed the Principal of the Institute and its growth continued.

...... Finally, a further word in appreciation of the untiring efforts of Mr. Tom Roberts on our behalf. He was a tutor and friend. He arranged for our accommodation in Cardiff when we took the examination and he was at Ammanford square to see us on our way to wish us well and to offer final words of advice. It is also well known in the area that Mr. Tom Roberts endeavoured to motivate his students for many years by holding us forth as a shining example for them to follow. As further evidence of our mutual respect, he still proudly carries on him a wallet with the inscription, "Presented by the First Matriculation Class'.

...... I subsequently took a Science degree and Diploma in Education at Swansea University and am now retired and in good health after a full and happy career in teaching, except for a period of war service in the Meteorological Office.

Mr. Bryn Banfield, B.Sc.. Dip. Ed. (1977)

APPENDIX 4

Abstracts from the Coal Mines Act 1911 relevant to the appointment, duties, qualifications, and examinations of coal mining officials.

Chapter 50 Part I

"2 (1) Every mine shall be under one manager who shall be responsible for the control, management, and direction of the mine, and the owner or agent of every mine shall appoint himself or some other person to be the manager of such mine. (4) The owner or agent of a mine required to be under the control of a manager shall not take part in the technical management of the mine unless he is qualified to be a manager. "5 (1) A person shall not be qualified to be appointed or to be manager of a mine required to be under the control of a manager, unless he is at least twenty five years of age, and is for the time being registered as the holder of a first class certificate of competency under this Act. (2) A person shall not be qualified to be appointed or to be an under manager of a mine which is not required to be under the control of a manager, unless he is for the time being registered as a holder of a first or second class certificate of competency under this Act.

There shall be two descriptions of certificates of competency under this Act, (that is to say)(1) First Class certificates. (2) Second Class certificates. "8 (1) For the purpose of ascertaining the fitness of applicants for certificates of competency under this Act, a Board, to be styled "The Board of Mining Examinations" shall be constituted by the Secretary of State. "14 (1) For every mine there shall be appointed by the manager in writing one or more competent persons (hereinafter referred to as firemen, examiners, or deputies) to make such inspections and carry out such other duties as to the presence of gas, ventilation, state of roof and sides, and general safety (including the checking and recording of the number of persons under his charge) as are required by this Act and the Regulations of the mine. "15 (1) A person shall not, after the first day of January nineteen hundred and thirteen, be qualified to be appointed, or to be a fireman, examiner, or deputy unless he:

(a) is the holder of a first or second class certificate of competency under this Act, is twenty five years of age or upwards and has had at least five years practical experience underground in a mine of which not less than two years have been at the face of the workings of a mine and

(b) has obtained a certificate in the prescribed form from a mining school or other institution or authority approved by the Secretary of State as to his ability to make accurate tests (so far as practicable with a safety lamp) for inflammable gas, and to measure the quantity of air in an air current and that his hearing is such as to enable him to carry out his duties efficiently and

(c) has within the preceding five years obtained from such approved school, institution or authority as aforesaid, or from a duly qualified medical practitioner a certificate in the prescribed form to the effect that his eyesight is such as to enable him to make accurate tests for inflammable gas and that his hearing is such as to enable him to carry out his duties efficiently, the expense of obtaining which shall, in the case of a person employed at the time as fireman, examiner or deputy, be borne by the owner of the mine.It should be noted that the main field of instruction for mining employees at the new Ammanford Mining and Technical Institute was to fulfil Sections 15(1) (a) (b) and (c) of the Coal Mines Act 1911.

Source:

Coleg Technegol Rhydaman (Ammanford Technical College), 1927-1977, Dyfed County Council 1977.END NOTE:

The provision of education in the Llandybie, Ammanford and Betws area has a long history, going back at least 270 years from the first circulating schools of Griffith Jones in 1731. This history is too long and detailed to be encompassed by one essay so it has had to be divided into several sections. And even this does scant justice to the rich and complex subject matter. It awaits a far more competent historian than the present author and will have to be far more scholarly than this patchwork quilt of a web site will allow. Still, we can but try. The various sections are:Education in Ammanford 1

Education in Ammanford 2

Amman Valley Grammar School from 1914 to the present

Amman Valley Grammar School – the beginnings

Betws Primary School

Ammanford Technical College

Gwynfryn College (Watcyn Wyn's School)Date this page last updated: August 24, 2010