WESLEYAN METHODIST CHAPELS

IN AMMANFORD

CONTENTS 1 Introduction 2 English Wesleyan Chapel 3 Welsh Wesleyan Chapel 1. Introduction

When Henry the Eighth couldn't persuade the Pope to grant him a divorce from his first wife Catherine of Aragon in order to marry Anne Boleyn, he hit upon the novel idea of forming his own church instead, making himself head of it in the process, and was thus able to grant himself his own divorce. And so English Protestantism was born, in circumstances that owed nothing to religious conviction or principles.

But it wasn't long before this new religion was to experience splits of its own, eventually leading to the bewildering number of non-conformist faiths we see today, and even more which have since disappeared. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries a whole menagerie of weird and wonderful Protestant sects was loosed on an unsuspecting England. Within a century of Henry the Eighth's death in 1553 a bloody civil war would be fought between Royalists and Republicans with religion at its heart. Here, Puritans and Quakers; Presbyterians and Episcopalians; Baptists and Anabaptists; Ranters, Levellers, Diggers, Congregationalists, Fifth Monarchists, Millenarians, Muggletonions, Arminians, and more, jostled for position and Henry's Anglican Church was in serious jeopardy for a while. Some sort of order was finally achieved only in 1660 when the monarchy, and with it the supremacy of the Church of England, was restored after twenty years of a Cromwellian interregnum. And in the midst of all this ferment Catholicism was still bubbling away, often clashing violently with the Protestant authorities.

Then in eighteenth century England yet another new movement, soon to be named Methodism by its followers, was formed by John Wesley within the same church Henry the Eighth had created in the sixteenth century. Wesley, an ordained Anglican vicar, didn't want his movement to break with the Church, merely for it to reinvigorate the rather jaded Anglican establishment. But within just four years of Welsey's death, English Methodism made a decisive break with the Church of England and became an independent denomination in 1795.

A similar, but separate, movement was afoot in Wales at the same time, led by such celebrated preachers as Howel Harries, John Rowland and William Williams, Pantycelyn, who rode the length and breadth of Wales evangelising the new faith in the Welsh, not the English, language. These men, though, were adherents of the theological ideas of the Frenchman John Calvin, not the Englishman John Wesley, so that the majority of Methodist churches in Wales are Calvinistic, where England is largely Wesleyan. And this explains why Ammanford's first Wesleyan Methodist church was founded by Englishmen, and why its services were in English for English families moving into the area. The Welsh Calvinistic Methodists, however, held their own vigorously and grew in numbers. In 1811 they, too, separated from the established Church and set up a new church, Presbyterian in polity.

The difference between these two forms of Methodism may be important to their respective adherents but to the non-theologically inclined, bafflement is a more likely response. Calvinists deny free will in humans, believing God to have pre-ordained everything when He created the universe and set everything in motion (they call it 'predestination'). Predestination is the belief that before the creation, God determined the fate of the universe throughout all time and space. God's foreknowledge extends even to the key precept of Christianity—salvation—because those who are destined for heaven (the 'elect') have been chosen in advance and can't do anything to change it. Further, Calvinists believe that it is impossible for those who are redeemed to lose their salvation.

Wesleyans, unlike Calvinists, believe that all can be saved, not just the 'elect'. Wesleyans, in other words, allow free will in humans, and how we live our lives can decide whether we burn in the afterlife or remain un-roasted and relatively cool. In addition, Wesleyans claim it is possible to lose your salvation.

Welseyan Methodist teaching is sometimes summed up in four particular ideas known as 'the four alls'.

- All need to be saved - the doctrine of original sin.

- All can be saved - Universal Salvation

- All can know they are saved - Assurance

- All can be saved completely - Christian perfection

A key dogma for Calvinist Methodists is 'predestination'. As a Calvinist theologion has written of this concept:

Predestination is the doctrine that God alone chooses (elects) who is saved. He makes His choice independent of any quality or condition in sinful man. He does not look into a person and recognize something good nor does He look into the future to see who would choose Him. He elects people to salvation purely on the basis of His good pleasure. Those not elected are not saved. He does this because He is sovereign; that is, He has the absolute authority, right, and ability to do with His creation as He pleases. He has the right to elect some to salvation and let all the rest go their natural way: to hell. This is predestination. (Matthew J. Slick, B.A., M. Div.)

As the same author writes: 'In response to this definition, some will protest: "Unfair!" It may seem so at first, but you will see that it is quite fair. More importantly, it is biblical.'

Some others may go further than claiming predestination is merely "unfair". Biblical or not, they might claim it is arbitrary, vindictive, or even sadistic. Many religions claim that God created man in His own image; might not man instead have greated God in his own image? The 18th century Scottish poet Robert Burns famously wrote of the Scottish Calvinistic God in his satiric poem Holy Willie's Prayer:

O Thou, who in the heavens does dwell,

Who, as it pleases best Thyself,

Sends one to heaven and ten to hell,

.....All for Thy glory,

And not for any good or ill

They've done before Thee!Why Welsh Methodists chose the more severe form of these two world-views is anyone's guess.

1 Introduction 2 English Wesleyan Chapel 3 Welsh Wesleyan Chapel 2. Ammanford English Wesleyan Church

At the beginning of the 19th century the main nonconformist denominations in Wales were the Independents, Baptists and Calvinistic Methodists, and the Independents were the largest denomination in Ammanford and the Amman valley. In 1851 the first ever—and last—religious census was undertaken and it showed that 75 percent of the Amman valley was Independent in its worship, with the established Anglican church trailing way behind with less than ten percent of the valley attending Church of England services.

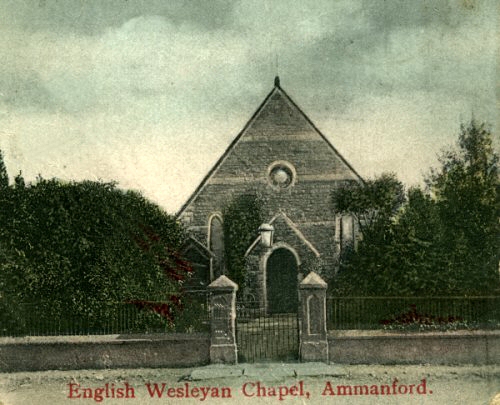

It was a migratory influence that attracted the Wesleyan branch of Methodism to the hamlet of Cross Inn, as Ammanford was called before 1880. A memorial tablet erected within the precinct of the English Wesleyan Church in Wind Street records its appreciation to one Samuel Callard. Its words announce that Samuel Callard: "with his father Thomas Callard came from Torquay in 1875, to erect this Church", also stating that "he was for 32 years, a most faithful worker as Trustee, Church Officer, School Superintendent and Preacher". Samuel Callard and his brother were involved with the management of the Amman Bridge Chemical Works in Pontamman and he died in December 1907 at the age of 60 years.

Ammanford Evangelical Church from 2003.But Wesleyan Methodists had a presence in Ammanford even before this, worshipping at the same chemical works that Samuel Callard took over in 1875. A building opposite the chemical works in Pontamman was recorded in the 1851 census as a Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, having a seating capacity for 72, with attendance at morning and evening services being recorded at 35. The Superintendent is recorded as one William Morris, who was also the proprietor of the chemical works at this time, so Wesleyanism in the town seems to have been imported by this one commercial enterprise. This building was also used as a school for children of the factory's employees, so the company appear to have been regulating just about every aspect of their employees' lives.

By 1906 a vestry or schoolroom had been erected to the rear of the building, financed in a novel way, whereby a contribution of half-a-crown would ensure the donor's initials would be engraved upon a yellow brick and built into the wall of the building. This way it was envisaged that the subscriber's name could to be seen for perpetuity, or at least as long as the church stood. 'Vanity, vanity; and everything is vanity … One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh', lamented the author of Ecclesiastes, and he may well be right. These bricks were located on the side elevation facing onto Lloyd Street. Due to a large crack appearing right down the wall of the vestry, it had to be demolished for safety's sake in 2008, though the yellow bricks have been kept by the church.

Throughout its life occasional use was made of the vestry by various organisations, who put it to such use as:

• A centre for pianoforte examinations. • Temporary sorting office for the Post Office during the Christmas holiday period. • Temporary storage and warehouse by Messrs Boots, Chemist. • An auctioneer's salesroom. • A meeting hall for the Ammanford Scouts. • A meeting place for the Ammanford Lodge of the Loyal Order of Moose. Like many other religious denominations, before and since, difficulties would eventually arise in sustaining membership. Even with the efforts of a few faithful stalwarts such as Mrs. Fletcher (Newsagent, College Street), Mrs. Seward Richards (Brynffin, Betws) and Mr & Mrs. Simms (Butcher, Wind Street), who organised a jumble sale in April 1957 in an attempt to raise funds for the Church, eventual closure was unavoidable.

The church struggled along until the late 1980s with declining membership, but the writing had been on the wall for some time, and English Wesleyan closed its doors for worship by 1990. For some years the premises remained unoccupied; then in 1993 an antiques and bric-a-brac salesroom was established in the vestry by an Abercrave businessman and his wife, who also acted as temporary caretakers of the property. The premises were placed on the market for sale in December 1995, being described as a "prime site, suitable for restoration or alternatively, for residential/commercial development". The Chapel was still at this period fully furnished with pews, pulpit, hymnal boards and even the wooden collection boxes. But the description of the church as a 'prime site' would prove to be the usual estate agent's hype and the building remained unsold for several years.

But salvation was soon at hand for the old building which was acquired by Ammanford Evangelical Church and restored to its former use as a place of worship. The current owners are a newer breed of church-goers than is familiar to Ammanford's long-established and, it is sometimes said, rather staid chapel worshippers. Overwhelmingly young (and overwhelmingly English speaking) they contrast starkly with the elderly and dwindling membership of Ammanford's older Welsh-speaking churches and chapels. This trend is now occurring throughout the whole UK where young, more vigorous churches, abandon outworn ceremonies, hymns and activities, pushing aside the old churches in the process. It is a trend the chapels of Wales are ignoring to their cost as they cling on desperately to a past no longer there, favouring tradition over change, but watching helplessly as change wins the battle.

The Welsh chapels of Wales are facing a major dilemma concerning the status of the Welsh language. For centuries religion was the custodian and defender of the language, at a time when many Welsh speakers were abandoning their native tongue for what they saw as the higher social status of English. It was the Circulating Schools of the Reverend Griffith Jones in the eighteenth century that taught an estimated 250,000 of the country's then 490,000 population to read, and it was Bishop Morgan's magnificent Welsh translation of the Bible they learned to read, not the foreigner's King James version. The Sunday School Movement, spearhead by the nonconformist chapels, added very high standards of writing in Welsh to this achievement in the nineteenth century. Now, in places like the Amman Valley, a growing influx of English speakers is changing the Welsh character of the area and those incomers who look for places to worship quite naturally turn to churches where services are conducted in a language they understand. The cruel paradox of Ammanford's Welsh chapels is that in protecting the heritage of their language, they may be hastening their own decline.

The English-speaking Evangelical Church, opened in 2003, now has one of the largest congregations for any place of worship in Ammanford, a town whose three major chapels once boasted some of the largest congregations in Wales. Christian Temple, Ebenezer and Bethany once numbered their memberships in thousands, not the hundreds (or less) of today's chapels. The Evangelicals were originally a breakaway from Ammanford's Plymouth Brethren church who, though they still worship in their own Gospel Hall in Lloyd Street, do so with a tiny membership compared to their Evangelical offspring. Founded in 1977, for many years the Evangelicals led a nomadic life, worshipping in various venues around Ammanford, including the local Pensioners' Hall and St John's Ambulance building, but the happy-clappy energies they bring to their worship was also successfully applied to fund-raising activities and their very own church building is now the fruit of these endeavours.

1 Introduction 2 English Wesleyan Chapel 3 Welsh Wesleyan Chapel 3. Ammanford Welsh Wesleyan Chapel, Tirydail

During all its history Ammanford and the Amman Valley have been overwhelmingly Welsh speaking. Even with the language in retreat this still remains the case today but was especially so at the beginning of the twentieth century, when over 90 percent of the population spoke the national tongue. There were few churches and chapels in Ammanford at this time who held services in English and the English Wesleyan Chapel on Wind Street was one of them. But Welsh-speaking Wesleyans were not to be outdone and soon rectified matters by building their own chapel.

Located on Tirydail Square Capel Wesleyan was a substantial building (quite in contrast to nearby Seion chapel's corrugated iron roof and walls) and was opened by Lieut. Col. W. N. Jones on the 6th of October 1911. The chapel had an imposing facade constructed in red and white 'arton' stone with a mock-gothic tower and spire based on a design described in those days as Old English, rather an inept description for a Welsh Chapel. It was lavishly equipped and furnished with a seating capacity for 350 and an annexe or vestry hall for use by the church for bible classes and Sunday schools. In all respects it presented a fine piece of architecture, equal, if not superior to many other such buildings in the town. The architect was Mr David Thomas of Ammanford and the contractor was Mr. David John of Tirydail.

Ammanford's Welsh speakers who chose Wesleyan Methodism over the dominant Calvinistic version led the usual vagabond life associated with a new church until membership and funds permitted them to raise their own building. The great 1905 Welsh Revival provided the impetus for Ammanford's Wesleyans, as indeed it did for all denominations, and under its spell people flocked to all the existing churches. Such was the growth in worshippers that many of Ammanford's chapels and churches built new annexes to accommodate the newly converted.

Initially the local Welsh Wesleyans entered into a lease in 1906 of a small property at the junction of Harold Street and Station Road previously occupied by the Christadelphians. After the Welsh Wesleyans built their own church in 1911 this was later leased to the local church authorities and used by them as a Sunday school. The new name of St John's Church was given to the building, though it was always known by Tirydail residents as Capel Bach (the little chapel). And going back even further Ammanford's Welsh Wesleyans had once held services in the schoolroom of Watcyn Wyn, in Brynmawr Lane (now the English Baptist Church).

In 1911, with the tumult of the great Revival of 1905 still ringing in people's ears, it would have seemed as if religion was here to stay forever. Ammanford was still growing in population too but, though no-one could have foreseen it then, 1931 would prove to be the year this growth peaked, to decline thereafter. Newer forms of social activity would evolve after the second world war which would first challenge, and then overthrow, the chapels as centres of community life.

Ammanford's Welsh Wesleyan Church, College Street, built in 1911. This photograph was taken shortly before its demolition in 1994. Thus in time, as has happened with many of the town's churches, membership dwindled to unsustainable numbers and services ceased in the late 1970s with the church's eventual abandonment. Welsh Wesleyan Methodism, the minority version in Wales, would last barely half a century in Ammanford. The church was sold to a private entrepreneur who visualised other uses for the building, none of which materialised. Eventually its valuable fittings and assets were removed, including the building's dressed stone, leaving the structure in a semi-demolished and unsightly state. All this happened quite literally overnight before anyone realised what was happening.

In 1994 Dinefwr Borough Council, who in the meantime, had acquired the property, made arrangements to remove the remains of the building and clear the site. Yet another place of worship, the vision and aspiration of a once loyal and dedicated membership, was no more, just a fading memory hovering over an empty patch of grass. Carmarthenshire County Council, who in 1996 became the Authority administrating local government affairs in the area, advertised the plot for sale in May 1999 as a two-acre site with outline planning consent for redevelopment for residential use. In 2010 the plot still stands empty.

At one point Ammanford's Wesleyan minister had five chapels in the area to serve, making his Sundays rather a busy day. Services would have to be staggered to take in Ammanford English Wesleyan Church (now Ammanford Evangelical Church); Ammanford Welsh Wesleyans (now demolished); Llandybie Wesleyans (now Llandybie Pensioners' Hall); Trap Wesleyans (now a private residence); and Llandeilo Wesleyans (also a private residence). No-one now visits any of them for worship.

Not long ago the little part of Ammanford known as Tirydail (Land of the Leaves, though there are few leaves left today) once boasted four places of worship within a hundred yards of each other, but these too have all passed into history. The Baptist Seion chapel built in 1913 was demolished in 1993 and replaced by a private residence. Welsh Wesleyan, as we've just seen, vanished from the earth in 1994. The little Calvinist Methodist chapel of Elim which opened its doors to the faithful in 1906 shut them just before Christmas 2002, by when its congregation had shrunk to just seven elderly worshippers, and the building has now been converted into two semi-detached houses. Capel Bach (real name St John's Church) was once a Sunday School for the Anglicans of Tirydail until it closed its doors in 1974. It was given a new lease of secular life in 1982 when the local branch of the Loyal Order of Moose bought it and renamed it Moose Hall. But the usual problem faced by mutual organisations in our less public-spirited age eventually reared it ugly head – declining membership – and the Ammanford Loyal Order of Moose is no more, having folded though lack of support around 2000. The building is currently the home of the Hafan Gobaith (Haven of Hope) Day Centre, run by the Amman Valley Dementia Carers' Support Group.

1 Introduction 2 English Wesleyan Chapel 3 Welsh Wesleyan Chapel