RAILWAYS AND THINGS

THE AGE OF STEAM

Click to go to

The Beeching Cuts

In this section we will take two photographic journeys along our local rail networks. One journey will pass through all the former stations along the Amman Valley branch line from Pantyffynnon to Brynamman and the other will take us from Pantyffynnon to Llandeilo along the 'Heart of Wales' line. All the photographs are from the days when steam trains plied up and down our railways and before British Railways scrapped them in favour of diesel-powered engines. While diesel locomotives may be more cost-effective than coal-fired steam engines, somehow the 'Age of Diesel' doesn't have quite the same romance as the 'Age of Steam'.

Except for those who use the network of commuter trains that encircle our larger cities, many people today, especially those living in rural areas, have little experience of rail travel any more. The car culture has become so much a part of our modern mind-set that a child taken on a train journey reacts as if it's a special event, while many of today's children have never experienced public transport of any kind, the school run having replaced the school bus. And we have closed so many of our village schools that parents have no option but to take their children to distant schools by car. In the predominantly rural districts of West Wales, public transport is little, if any, better than it was in the middle of the nineteenth century.

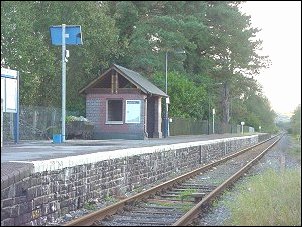

For many, it seems that train journeys are a thing of the past, as are the best-kept station competitions once held by the railway companies. Railway station staff took great pride in their waiting rooms and spent hours tending their little gardens on the station platforms, cultivating flowers and even vegetables while waiting for the Down or the Up train to arrive. With the privatisation of the rail network, and the sale of the track and stations to Railtrack, the deterioration of our stations has been as dramatic as it's been unnecessary. And while it is still well worth taking a train journey on the beautiful 'Heart of Wales' line from Swansea to Shrewsbury, many of the stations glimpsed through dirt-smeared windows present a sorry sight indeed. Grass and weeds have colonised many of them; windows have been boarded up; graffiti defaces the buildings and waiting rooms, while paint is left to peel on doors, windows and signs. If Railtrack were to introduce a similar competition today, 'the station with the biggest rat colony' is a more likely title they'd chose.

If you do travel by train, ponder what has disappeared from view as you arrive at your station to start your journey. Gone are the uniformed staff, the station foyer, the booking office, the refreshment and waiting rooms, and the posters advertising holiday resorts to add a splash of colour to the surroundings. Nor will you see or hear the family groups off to the seaside any more, the children clutching their buckets and spades in a state of excitement you could almost reach out and touch. Being stuck in a motorway tail-back en route to a theme park seems to be the preferred option for today's families. And gone too are the signal boxes, the level crossing gates and the white picket fences that were once such a pleasing part of a village's architecture.

Only in the mind can we revisit those earlier days now, with memory jogged occasionally by a few old photographs luckily preserved from time's ravages. To help you jog that memory take a look of these photos of local railway stations from the age of steam, which ended in our area in 1964. Here you can take a journey in your memory along the 'Heart of Wales' line, not on today's single-carriage diesel trains, but along a real hissing and puffing steam train, stopping at Pantyffynnon, Tirydail, Llandybie, Fairfach and Llandeilo on the way. And if your memory can take you back before 1958, the year they closed the passenger service along the Pantyffynnon to Brynamman branch line, then buy your ticket and travel up the Amman valley to Ammanford, Ammanford Colliery Halt, Glanamman, Garnant, Gwaun Cae Gurwen and Brynamman.

The names alone of our railway stations are enough to evoke a sort of boozy nostalgia, even when sober. Michael Flanders and Donald Swan, a musical duo in the fifties and sixties, wrote an elegiac little song about vanished railway stations called 'Slow Train'. The place names mentioned in the lyrics celebrate English branch line stations, but the names of our own Welsh stations have their own poetry too.

.....................Slow Train

....by Michael Flanders and Donald Swan

[Click HERE to hear the song on You Tube](Spoken)

Miller's Dale for Tideswell, Kirby Muxloe,

Mow Cop and Scholar Green.(Sung)

No more will I go to Blandford Forum and Moretehoe

On the slow train from Midsomer Norton and Mumby Road;

No churns, no porter, no cat on a seat

At Chorlton-cum-Hardy or Chester-le-Street.

We won't be meeting again

On the slow train.I'll travel no more from Littleton Badsey to Openshaw;

At Long Stanton I'll stand well clear of the doors no more;

No whitewashed pebbles, no Up and no Down

From Formby Four Crosses to Dunstable Town.

I won't be going again

On the slow train.On the main lLine and the goods siding

The grass grows high

At Dog Dyke, Tumby Woodside

And Trouble House Halt.

The sleepers sleep at Audlem and Ambergate.

No passenger waits on Chittening platform or Cheslyn Hay.

No one departs, no one arrives

From Selby to Goole, from St Erth to St Ives.

They've all passed out of our lives

On the slow train

On the slow train.(Spoken)

Cockermouth for Buttermere.(Sung)

on the slow train.

(Spoken)

Armley Moor Arram … Pye Hill and Somercotes.(Sung)

on the slow train.(Spoken)

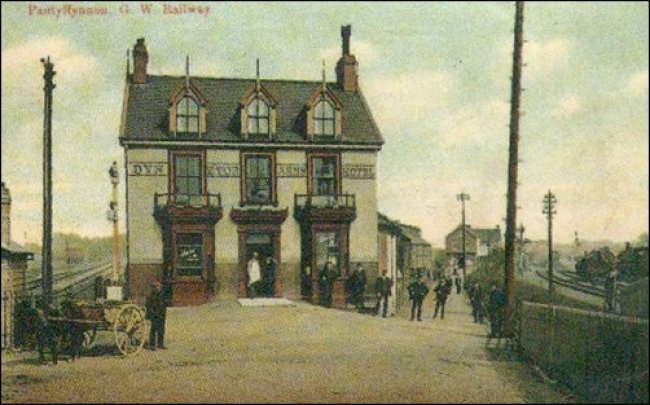

Windmill End.So pause awhile and take a 'Slow Train' of the mind along the two lines serving the Amman valley and district. In the photograph below of the Dynevor Arms public house in Pantyffynnon, both the railway lines of our imaginary journey can be seen. As we look north we can see the Swansea to Shrewsbury main line on the left with the Brynamman branch swinging eastwards to the right.

The Dynevor Arms Hotel, built in the 1880s, takes its name from the Dynevor Tinplate Works in Pantyffynnon (just left out of the picture). The Tinplate Works had been built in 1880 and in 1943 was the last of the five tinplate works in the Amman Valley to close. The huge building, which once housed rolling mills and other heavy machinery was demolished in the early 1970s. Another tinplate factory was built on the site, though much smaller, and which bears the same name of Dynevor Tinplate Works, but only as a tinplate stockist and merchants. The Dynevor Arms Hotel, named after the tinplate works and catering to its legendarily thirsty workforce, became a landmark in Ammanford due to its fine exterior and equally fine interior. It was mentioned in the 1906 edition of Kelly's Directory as the Dynevor Arms Commercial Hotel.

LINKS:

Amman Valley Railway Society

There is a web site for the Amman Valley Railway Society, with more history and photographs, which can be found on: http://ammanvalleyrail.netfirms.com/Heart of Wales Line Travellers' Association' (HOWLTA) Today Ammanford is one of about 40 railway stations on the Heart of Wales line which runs directly from Swansea to Shrewsbury. The line has its own group of entusiasts called the 'Heart of Wales Line Travellers' Association' (HOWLTA). Their web site can be found on www.heart-of-wales.co.uk/

Photograph Gallery (click to enter)

Pantyffynnon to Brynamman

Pantyffynnon to LlandeiloTHE BEECHING CUTS

No post-war history of Britain's railways is complete without at least a mention of the near-legendary Dr Richard Beeching. While most of the cuts to Britain's railway network are attributed to the grand 'Beeching' plan of the 1960s, the pruning of our branch railways had started much earlier than that. The Amman valley branch line from Pantyffynnon to Brynamman was closed to passenger traffic in 1958, closely followed by the complete closure of the Llandeilo to Carmarthen line in 1960. The line along the Swansea valley from Brynamman to Swansea, St Thomas, had already been axed even earlier in 1950. However, the infamous Dr. Beeching, who published the report that bears his name in March 1963, deserves at least some mention, especially as his name is being ominously resurrected in 2003 amid mutterings of cutting even more railway lines. We shall see, too, that sleaze in politics goes back quite a way and is not such a modern phenomenon as events of recent years might suggest.

DR BEECHING: THE NOT-SO-MAD AXEMAN

With the publication, in 1963, of 'The Re-shaping of British Railways' Britain's transport system would never be the same.

It's March 1963 and the future of Britain's railway system has just been settled with the publication of a dry and dusty looking booklet called 'The Re-shaping of British Railways'. But inside the plain blue covers, it was dynamite.

Written almost entirely by the recently appointed chairman of the British Railways Board – a hitherto unknown industrialist called Dr Richard Beeching – it proposed closing almost a third of the network, around 5,000 miles. Over 2,000 stations would shut, thousands of passenger carriages would be scrapped, along with a staggering third of a million freight wagons.

It was nothing short of seismic. But Dr Beeching saw his reforms as the only way to save the railway network from financial meltdown. Ever since the mid-1950s the rail system had been losing money. By the early 60's, cash – many millions of pounds a year – was just pouring into a black hole. The Government decided enough was enough.

Beeching's plan was a simple one: He began by looking at where the railways actually lost money – which services and lines were responsible for the deficit. That would tell him what railways did well and what they did badly. His plan would then concentrate on what they did best.

He made two basic findings: firstly that around 95 per cent of all rail traffic was being carried on about 50 per cent of the network – the remaining 50 per cent was hardly used. Secondly, he found that what railways did best was high speed, long distance bulk haulage—whether passenger or freight, the conclusions were the same.

That is why his report proposed closing hundreds of branch lines. They were hopeless loss-makers, his report said, and always would be. He also proposed taking local stopping trains off lines that were to remain open. They also lost money. Similarly, local goods trains would be chopped and wayside goods depots closed along with the passenger stations.

Instead, railways would focus on what they did best. Passenger trains would be re-invented. Beeching came up with the Intercity concept of high speed expresses connecting the major towns and cities. It is still how Britain's railways are run.

It was the same story for freight. Traditional goods trains would be replaced by two new types: block trains running between major centres carrying a limited range of goods—coal, aggregates for building work, oil and petrol and so on—and container trains carrying smaller loads which could be quickly switched from trains to lorries for collection and delivery to places off the rail network. Beeching reckoned a loss of over £30m a year would become a profit of £12m a year within eight years. However, as we shall see below, he was wrong.

The first wave of closures was quickly pushed through. But protest groups began forming to combat his closure plans. In most cases they had little effect. But the campaigners did score a few notable victories. The lines from Manchester to Buxton and Leeds to Ilkley were earmarked for closure but saved after hard-fought campaigns. So were lines to places like Kyle of Lochalsh, Mallaig, Thurso and Wick in the Highlands of Scotland. Half a dozen branch lines in the West Country to seaside towns such as St Ives, Newquay and Looe were also reprieved.

Was it worth it? Opinion is still divided. Beeching's fans—and there are lots of them, including many professional railwaymen—say yes. They reckon Beeching saved the railway from financial meltdown and a far bigger closure programme.

But others disagree. They say mistakes were made and some lines were closed that under any rational scheme would have stayed open, including the Great Central main line from London to Nottingham. It had been built to Continental standards, and was capable of carrying European sized carriages and wagons which are too big for most British lines. It could today be carrying Channel Tunnel trains all the way to Sheffield. But there was another, more sinister reason why the newly modernised London to Nottingham line was closed—greed.

Enter Ernest Marples

Beeching had been appointed to his post as head of British Railways by Tory transport minister Ernest Marples (later 'Sir', and later still 'Lord'). Marples (1907 – 1978) was not just a government minister, he also owned a construction company, Marples-Ridgeway. Marples-Ridgeway's main concern was—wait for it—constructing roads. They contributed to several motorway projects during the fifties and sixties and also constructed the Hammersmith flyover in London. When it was pointed out that being transport minister as well as a road builder might be construed as a conflict of interest he (grudgingly?) agreed, and divested himself of his shares in Marples-Ridgeway—to his wife! Sleaze, anyone...?In 1959 Ernest Marples had given the go-ahead for Britain's first motorway, the M1 which initially ran from London to Nottingham and followed closely the London to Nottingham railway line. Which company was given the contract to build the M1? Marples-Ridgeway, of course. And when Marples then closed the railway line there was no other way for people or freight to get from London to Nottingham than by road.

It is quite astonishing, with even a little thought applied to the matter, that the person responsible for closing the railways was also getting the contracts to build the roads that would have to replace them. It was Ernest Marples who closed one third of Britain's railways, not Beeching, who was merely the civil servant who wrote a report on the subject.

In the 1970s Marples, now retired from active politics, became 1st Baron Marples of Wallasey, but even a title was not enough to protect him when other aspects of his shady past soon caught up with him. His pursuer was the Inland Revenue who were chasing him for unpaid taxes on his extensive slum property empire. Former Daily Mirror editor Richard Stott investigated Ernest Marples in 1975 and has left his memories of him in his autobiography, published in 2002.

"In the early 70's the vultures were circling as he tried to fight off a revaluation of his assets which would undoubtedly cost him dear ... So Marples decided he had to go and hatched a plot to remove £2 million from Britain through his Lichenstein company ... there was nothing for it but to cut and run, which Marples did just before the tax year of 1975. He left by the night ferry with his belongings crammed into tea chests, leaving the floors of his home in Belgravia littered with discard clothes and possessions ... He claimed he had been asked to pay nearly 30 years' overdue tax ... The Treasury froze his assets in Britain for the next ten years. By then most of them were safely in Monaco and Lichtenstein." (Richard Stott, 'Dogs and Lampposts', Metro Publishing, 2002, pages 166 – 171)

In addition to being wanted for tax fraud Marples was also being sued in Britain by tenants of his slum properties and by former employees but he never returned to face the music—or pay the bills. Marples died in 1978, having never returned to Britain and so was able to keep his tax-evaded wealth and see his life out in luxury in his French chateau in the heart of the Beaujolais wine-growing area. And there, incredibly, is the story of the man put in charge of Britain's transport policy in the fifties and sixties.

Back to the Beeching Report

As railway deficits continued to rise in the 1950s, the Conservative government had set up a committee in April 1960 which was chaired by a director of Tube Investments, Sir Ivan Stedeford, to examine the structure, finance and working of a policy-making British Transport Commission, the BTC, particularly its railway activities. The committee included Dr. Richard Beeching—the future chairman of the BTC and the British Railways Board (BRB). The Treasury and the Ministry of Transport were also represented but there was no place for the BTC or the rail unions. The minister, Ernest Marples, "steadfastly declined to appoint representatives of the railway unions or of the BTC to the Committee. He claimed it would be wrong to include people who were themselves concerned." (Source: P.S.Bagwell, The Railwaymen, Volume 2, Allen & Unwin, 1982). But clearly not wrong to include himself who, as owner of the construction company that was building much of Britain's new roads, most definitely was concerned. Those who think sleaze in government is a recent invention might now think otherwise.The report of the Stedeford Committee was never published but the recommendations for the future of the railways were and these became known as the 'Beeching Plan'.

And the savings that Beeching expected to make never materialised. He reckoned in 1963 that closing the branch lines would save £30m. In fact, the closure programme saved less than a quarter of that – just £7m. In addition to cutting 5,000 miles of Britain's 17,000 mile rail network, the Beeching Report had also proposed that 3,000 miles of rail track should be upgraded as well. That, however, was mysteriously never implemented.

Interestingly, Beeching and Marples refused to publish the figures which they had used to claim the rail network was losing money, including a special formula to calculate the profitability of a railway line. When, in recent years these figures were finally examined, many of the branch lines claimed to be loss-making back in 1963 could be demonstrated to have been making profits.

And there is still talk of re-opening some of the lines that Beeching closed. But doing it would be hugely expensive and so far there's only one example of it happening—the Robin Hood Line between Nottingham and Mansfield.

Epilogue – "No one left and no one came...."

Perhaps the best known branch railway station in Britain is Adlestrop in Gloucestershire, thanks to the poem of that name by Edward Thomas, though this fame offered no protection from the Beeching cuts. The station, now closed, was half a mile from the village of Adlestrop, which is between Stow-on-the-Wold and Chipping Norton on the Gloucestershire-Oxfordshire border. The name-board was salvaged from the station's demolition and now hangs in the village bus shelter as a memorial!!!Adlestrop

Yes, I remember Adlestrop – The name, because one afternoon

Of heat the express-train drew up there

Unwontedly. It was late June.The steam hissed. Someone cleared his throat.

No one left and no one came

On the bare platform. What I saw

Was Adlestrop – only the nameAnd willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.And for that minute a blackbird sang

Close by, and round him, mistier,

Farther and farther, all the birds

Of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.(Edward Thomas, written 8th January, 1915)

Source: Much of the above is a summary of BBC Radio 4 programme 'Back to Beeching' broadcast on Thursday 27 February, 2003

Photograph Gallery (click to enter)

Pantyffynnon to Brynamman

Pantyffynnon to Llandeilo