By Winifred Griffiths

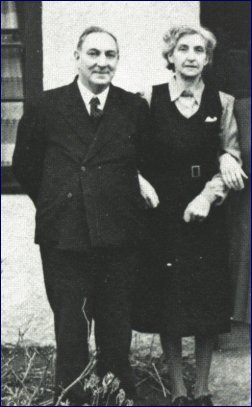

Winifred Griffiths was born in Overton, Hampshire in 1896. She became influenced by socialism following her experiences as a worker in a clothing factory and in domestic service. She worked in the Co-op before and after her marriage to James Griffiths in 1918. He was later to become an M.P. and Cabinet Minister [there are three essays on Jim Griffiths in the 'People' section of this web site]. In 1927, she became a member of Ystradgynlais Labour Party Women's Section, and served as a Poor Law Guardian (1928-30), a District Councilor (1928-36) and a magistrate. From 1932 to 1935, she contributed a series of articles to the Social Democrat chronicling her experiences. Her husband's career took the family to London, bringing to an end her personal political activity in South Wales. Her autobiography, 'One Woman's Story', was published in 1979, from which this extract is taken.

About three weeks after Jim [Griffiths] and I were married the glorious news broke on the world that the war was at an end and an armistice would be signed. The colliers had a day off work and Jim and I went to Llandeilo Fair. What a load seemed suddenly to be lifted from all our hearts, and with what hope we all said "never again"! Now there was to be an election for a new government to tide over the transition from war to peace and from an economy geared to the service of the armed forces to one geared to peacetime requirements.

It was my first taste of an election campaign and I sampled all the various jobs. It was the very first election in Britain in which women were allowed to vote. Even so I failed to qualify as I was under thirty years of age (see note 1 below). However, this disqualification did not deter me from trying to persuade others more fortunate to vote for the Labour candidate, especially as he advocated votes for women on the same basis as men. I was happy to do any of the other work but when my husband pressed me to go and speak at meetings, I felt very apprehensive. After some hesitation I came to the conclusion that I must have the courage of my convictions and do my best – even if I risked making a fool of myself. As luck would have it the first meeting to which I was assigned was in a small mining village a few miles away. It was held in a chapel vestry and my little speech about women's rights, and how unfair it was that we had not got equal voting rights with men, got a rather cold reception. The all male audience obviously had some doubts about even the women over thirty being allowed to vote. They did not seem at all enthusiastic about demanding any more freedom for their women folk ... (see note 2 below).

Our candidate Dr Williams polled 14,409 votes as against the 1,176 he had polled in the by-election of 1910. We were overjoyed at the result and confident that next time we would win the seat. In the meantime propaganda must continue. The Trades and Labour Council [the local TUC] organised meetings, sometimes outdoors on Ammanford Square, sometimes indoors in the shabby Ivorites Hall (see Note 3 below). Besides local speakers my husband was able occasionally to get speakers from further afield. One interesting visitor was Sylvia Pankhurst, the only one of the Pankhurst family who was a Socialist as well as a Suffragette. She suffered badly in health as a result of the forcible feeding she had endured when on hunger strike in prison. The only way we could put her up was for her to share a room and large bed with a little girl, an orphaned niece of Mrs Jenkins, our landlady.

In our small working-class homes we almost always had to 'double up' and share in this way, and we thought nothing of it. However when Sylvia arrived and heard of our arrangements for her, she objected strongly and said she must have a room to herself. At first I was inclined to be resentful of what I thought was an example of middle class snobbery, until Jim soothed me by saying that 'poor thing, her nerves are so bad that perhaps she can only sleep if she is alone.' In the event we all went off to the meeting, from where a comrade was sent out to scout around for a suitable room. Sylvia's speech was about a visit to Soviet Russia from which she had only just returned. We had, as Socialists, hailed with delight the Russian Revolution of 1917. We had regarded it as the beginning of the triumph of our ideas. But already in 1919 the golden vision was a little tarnished. Stories came out of Russia which gave rise to doubts, but still we hoped. Sylvia had been full of confidence in the revolution and had gone out to make contact with its leaders. But alas, she had returned disillusioned and sad…but hope springs eternal – we could not so easily discard our faith in the great Russian Revolution and its implications for the workers of the world.

NOTES:

(1) The Suffragettes

Campaigns for voting rights for women, who were excluded from the electoral process, had started in the nineteenth century, although most of the working class were also excluded, with the vote only given to property owning men. In the 1880s, out of a population of 27.5 million only 4.5 million men were able to vote in General Elections. The 'Suffragette' movement properly speaking dates from 1903 with the formation of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in that year. The best known of the Suffragettes were the Pankhurst family, Emmeline (or Emily) and her two daughters Christabel and Sylvia. It was Emmeline who had formed the Women's Social and Political Union and its newspaper, called 'The Suffragette', gave its name to the movement generally. (The word comes from 'suffrage' which means a vote, or right to vote).Emmeline's husband Richard Pankhurst had achieved some limited voting rights for women when he had drafted an amendment to the 'Municipal Franchise Act' of 1869 which allowed some women to vote, but only unmarried and widowed women who were householders, and then only in local council elections. This right was not extended to married women until 1894. (Why were married women not trusted to vote, is the question that suggests itself.)

From 1905 onwards the Suffragettes embarked upon a campaign of civil disobedience, including breaking the law. The most well known – and horrific – act was when one suffragette, Emily Wilding Davison, threw herself under the hooves of the King's horse running in the 1913 Derby and was killed. As the result of the Suffragettes' campaign women over 30 years old were finally granted the vote in 1918 but it wasn't until 1928 that they were allowed to vote on equal terms with men, that is, everyone over 21 years of age who was a rate payer or married to a ratepayer. It wasn't until 1945 that our current 'one person, one vote' system – ie all adults – was introduced in mainland Britain and not until 1969 that this basic human right was extended to Northern Ireland. The United Kingdom (ie England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland), was thus one of the last modern states to introduce full democracy into its electoral procedure.

The Suffragette leadership had called off their civil disobedience campaign when war broke out in 1914 and backed the war effort, and the government released all Suffragette prisoners. Women flooded into the factories and other workplaces to take the place of their menfolk, millions of whom had been sent out to fight in the trenches. As war progressed it became increasingly difficult for opponents of universal suffrage to claim that women were somehow 'inferior' to men when they were doing the same jobs in the munitions factories, on the farms and in almost every other occupation that previously only men had done. Even so, over 1,000 women had been imprisoned before the government conceded in 1918. Many of those imprisoned had gone on hunger strike while in gaol and had been force-fed to keep them alive, Sylvia Pankhurst among them, as Winifred Griffiths alludes to above. The feeding was particularly brutal and was achieved by forcibly pushing two-foot long tubes up their nostrils into their stomachs and then liquids being fed to the women through these tubes. Think about that; or better still, don't.

Some Web Sites:

Click here for a web site on the Suffragette movement: http://www.cjbooks.demon.co.uk/suffrage.htmClick here for a web site on Emmeline Pankhurst: http://www.thehistorychannel.co.uk/classroom/gcse/womenstatus1.htm

Click here for a web site giving a timeline for voting rights from the Magna Carta of 1215 onwards: http://www.netcentral.co.uk/steveb/dates/votes_justice.htm

(2) While such opinions are held, even today, by men, it can come as a surprise to discover that many women also shared these views about women's equality, so persuasive were the spurious arguments used against equality for women. Maggie Pryce Jones is from Trelewis in the Rhondda, a similar mining community to Ammanford, and here is her description of her childhood growing up between the wars:

My passion for education was instilled in me at our village's autumn flower show in about nineteen twenty nine, I think. I was there with Am because Dad was showing his dahlias. The show was held in a large dirty white tent on our local playing field.

...... The air inside the tent was hot and humid, heavy with the scent of the different flowers. I remember we were admiring the colourful displays. Mam loved flowers but did not like to see them cut from their own environment. 'Poor things,' she said as she touched the velvet petals in the vases and jugs.

...... We reached the benches where the chrysanthemums in all their magnificent glory were on show, their wonderful colours, red, gold, bronze and blood-red made a wonderful display.

...... 'Oh, chrysantememums,z' exclaimed my Mam in delight. 'No perfume Maggie, but aren't their colours wonderful?' A thin high voice spoke from behind us, 'You mean chrysanthemums Martha, if you could read you would know,' it said spitefully. It had to be my aunt, the toffee-nosed one of course. I saw my quiet mother blush and turn away, and I with all the dignity of a young child, said slowly and loudly, 'My Mam can read anything that you can.' I remember the silence in the tent then Mam took my hand and we left the show and went home. Mam never mentioned the matter afterwards, now I know she was ashamed because I knew of her lack of learning.

...... Later that week I asked Grannie, who lived with us, why my mother could not read. 'Does it matter, child, as long as there is food on the table and the beds are clean?' she demanded. 'A woman does not need to read or write. Our work is in the home, the men see to all else, and that is how it should be.'

...... I knew that it did matter. The incident stayed in my mind, fostering a deep rebellion inside me. Unknowingly I hoarded such incidents, asking repeatedly why I had to help in the house while my brothers played outside. The answer was always the same. 'You will have a house of your own to look after one day Maggie, the boys will have wives to look after theirs.'

...... I began to notice that Mam always saw that Dad had the best food, the most comfortable chair, and new clothes when he went out anywhere with the Legion. She had nothing and never went out unless all our family went as well. The one thing I could not understand as I grew older was – why did she accept it all? Our neighbours, her friends were exactly the same, the men had first claim on luxuries and their wives were happy to accede to this as their due. 'After all they work hard, Maggie,' Mam said one day when I asked her why she spent all her club money on Dad and us children – nothing for herself.

...... John, our lodger, told me one day when we were discussing the matter on one of our walks, 'I think it is hard on the women, cariad, but nothing will ever change I am afraid, because the women themselves see no wrong in it.' I often sat in the room when one or other of Mam's friends came in, their talk was always about their homes and family, they went nowhere, they saw few people, only their neighbours or families, and as most could not read they had no other topic of conversation.

...... In those days, voting day was a big event, schools were closed because they were called into use as voting stations. Husbands and wives went to vote together, I remember hearing Mam tell John when he asked her who she thought was the best candidate 'Lew will tell me who to vote for', and so it was, wives voted as told by their husbands.

...... I was fifteen when Mam died, and how I wished that my brothers had learned to help in the house, they were good and tried hard but it was difficult for them to come to terms with it.

...... I vowed then that any children I might have would be treated equally, whatever their sex, and more, I would see that they would have the best possible education. If only Mam and her peers had known and recognized the power they held. They were the strong ones, not the men. They had the iron hands in their velvet gloves.

...... The women of the valleys were forced to use that strength in nineteen thirty nine and in the years that followed. Then, they broke the chains that held them to their kitchens, they thought for themselves, and they changed the history of the valleys, as women elsewhere changed the history of this country."Chrysanthemum is Hard to Spell" – Maggie Pryce Jones

Maggie Pryce Jones was born in Trelewis. She was forced to leave grammar school at fifteen to bring up her younger siblings when her mother died. She returned to education during the 1960s, gained her '0' and 'A' levels and worked for many years in the Civil Service. She started writing, a long held ambition, when her husband suffered a stroke and became bedridden for six years. Her published work includes poetry and her autobiography 'Kingfisher of Hope'. Her latest novel, 'White Doors, Black Memories', is awaiting publication. Maggie has two Sons and two daughters and lives in Treharris.

(3) The Ivorites Hall

Hall Street in Ammanford takes its name from the Ivorites Hall which was originally built on thw road by the grandly named 'Philanthropic Order of True Ivorites, St David's Unity, Friendly Society' – motto: 'Cyfeillgarwch, Cariad a Gwirionedd' (Friendship, Love and Truth). This was one of the many Friendly and Mutual Societies that sprung up in the nineteenth century, working men's self-help groups that were the forerunners of our modern building societies, insurance companies and trades unions. The Ivorites Order had been established in Wrexham in 1836 by Thomas Robert Jones ('Gwerfulyn', 1802-1856) and it was the only Working Men's Society which was exclusively Welsh. The 'Ivorite's' were named after Ifor Hael (Ivor the Generous) who was the patron of Dafydd ap Gwilym (David son of William), the C14th poet, and he lived at Bassaleg, Monmouthshire. In 1838 the St David's Lodge in Carmarthen was formed with powers to act as the principal lodge for the Order in South Wales but by 1840 there was a split in the Ivorites movement and Thomas Robert Jones lost control. The Carmarthen lodge was the chief lodge in Wales until 1845 when the central office moved to Swansea (and where there are still two public house called 'The Ivorites' to this day). The Ivorites had firm rules for its members regarding morals and behaviour; it nurtured the Welsh language and during its golden years between 1840 and 1870 there was hardly a year without an Ivorite Eisteddfod. This cultural activity puts the movement in a special category and assisting the poor and needy was not its only purpose.Within one year of the St David's Lodge being formed in Carmarthen in 1838 it had fulfilled its function admirably with ten branches established in Carmarthenshire alone which included an Ammanford Branch, called the Glanllwchwr Lodge. Glanllwchwr Lodge of Ivorites was established on 4 March 1841, had 51 members in 1848, and their total assets amounted to £120.00. The lodge must have flourished for within a short period of time sufficient funds was accumulated to build a substantial building to be known as the 'Ivorites Hall' in what was then called Chapel Road. The Hall must have had considerable prestige – and use – for the road eventually became called 'Hall Street', the name it is known by today. Prior to the Hall being built the Order's meetings took place in local hostelries, as did the neighbouring lodges in Llandybie and Llandeilo. The actual date of the opening of the Hall cannot be traced but it is known that an eisteddfod was held at these premises in 1879. The 1910 edition of 'Kelly's Directory for South Wales', describing Ammanford, has this to say of the Hall: "The Ivorites Hall is used for concerts, theatricals and public meetings, and will seat about 1,600 persons." Even today this would be a sizeable premise.

While the aims of the Order were partly that of a conventional Friendly Society, namely to foster unity and fraternity and to assist one another in sickness and adversity, they also took on another important role by promoting the practice of speaking and writing the Welsh language. Clearly, in naming themselves after the patron of Wales's greatest poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym, they wished to emulate Ifor Hael's great service by extending their patronage to the the Welsh language and Welsh literature generally. This description of the nearby Llandeilo Ivorites in 1840 gives an idea of the idealistic and moralistic motives of the Ivorites:

"There is only one Society of Ivorites in the Town [ie Llandeilo] which was commenced in the month of September, 1840, and consists of eighty members. The state of its finance is very healthy, the sum total being £400. The "Order of Ivorites" has done a vast deal, of late, towards the fostering of Welsh literature by giving prizes, and holding congresses to bring out native talent. It may be termed a good Institution for the working class, as it has in view their intellectual, as well us their moral and social improvement. This society is held at the Red Cow, Bridge Street."

['Llandeilo-Vawr and its Neighbourhood, Past and Present', by William Davies (Gwilym Teilo), page 21, originally published in 1858 and reprinted by Dyfed County Council in 1993].

In keeping with many organisations of the working class at that time, the Ivorites had much of the paraphernalia now associated with today's Freemason's and Orange Orders – secret signs and handshakes, passwords, oaths of secrecy and the rest. When the Ivorites were formed in 1836, associations of the working class, especially trade unions, were heavily restricted in their activities by the state authorities, even banned, and this gave rise to a climate of secrecy and suspicion. The Ivorites gave a special booklet to each member in which 15 signs and handshakes, or 'grips', were illustrated and explained (in both Welsh and English). We are shown, for example, a sign for "Warning a brother of danger", and "Assuring a brother of his safety without speaking to him". There were severe fines for revealing details of a lodge's business to outsiders and in their rule book as late as 1920, we see the following: 'The Unity Secretary shall issue a password every six months to enable members to obtain admission into Lodges and also a password annually for the use of travelling members (section 43 (1)). While such practices were, by 1920, purely ceremonial they offer a glimpse into a past when they would have had a practical basis.

The Ivorites were especially keen on the conduct of its members during meetings. In their 1897 rule book the following are just some of the fines levied on misbehaviour:

62 Rules to be observed at Lodge meetings When a member addresses the officer presiding he shall be standing, or be fined 3 pence, and any member interrupting another whilst addressing the lodge shall be fined 6 pence for each offence. Any member intoxicated at a meeting shall be fined 5 shillings for a first offence, 10 shillings for a second and 21 shillings for a third a subsequent offence If a member neglects to address the present or past officers by their respectful titles, he shall be fined 3 pence. If a member swears, sings an indecent song or gives and indecent toast or sentiment, or lays or offers to lay wagers he shall be fined 1 shilling. Along with the Rechabites Hall, which stood on what is now the Railway Hotel, the Ivorites Hall in Ammanford provided a venue for meetings, concerts and other gatherings, often of a political nature. The Ivorites Hall flourished as the only such place in Ammanford until the Working Men's Clubs took over that role in the 1930's. (The Rechabites, founded in 1835, were a Temperance organisation advocating the abolition of drink.). The role of the Ivorites, as well as promoting the Welsh language, was in keeping with other Friendly and Mutual Societies of the time, which included providing for members in financial difficulty, or in sickness, or those unemployed, and providing assistance for widows including burial expenses. Essentially, their financial role in those days before the welfare state was that of a modern day insurance company with benefits paid from the weekly contributions, or premiums, of the members. When the Welfare State, and other organisations took over these and similar roles in the twentieth century, the Friendly and Mutual Societies were forced to adapt or die. Our modern Building Societies, Insurance Companies and Trades Unions are the direct descendants of those who obeyed the Darwinian imperative and adapted – think of the number of modern insurance companies who have the word 'Friendly' or 'Mutual' in their titles. The Ivorites didn't, or wouldn't change, and on the 31st of December 1959, after a dissolution vote of 922 members for and 25 members against, the Ivorites ceased to exist. But even by the time of the First World War the Ivorites Hall in Ammanford had seen its best days, as Winnie Griffiths describes above:

"The Trades and Labour Council [the local TUC] organised meetings, sometimes outdoors on Ammanford Square, sometimes indoors in the shabby Ivorites Hall."

The only visible evidence of the Ivorites now are two public houses named after them in Swansea, the fossil remains of their past existence.

The Ammanford & District Miners Hall and Welfare Institute was opened in 1932 and Ammanford Social Club (the 'Pick and Shovel') in 1936 and these took on the role previously played by the Ivorites Hall in Ammanford's political, social and cultural life. The Ivorites Hall was rented to the government for a while and it was used as the local Employment Exchange until the government bought it outright in 1968, promptly demolishing it and building the custom-designed Job Centre that currently stands in its place.

Sources:

The Source for both the Winifred Griffiths and Maggie Pryce Jones stories above is 'Struggle or Starve, Women's lives in the South Wales Valleys between two World Wars', edited by Carol White and Sian Rhiannon Williams, (Honno, 1998). A visit to the archives of the South Wales Coalfield Collection, held at Swansea University, yielded some of the material on the Ivorites.