----------------------------------------------------------FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF

EDWARD THOMAS (1878-1917)

'SOME OF HIS WELSH FRIENDS'----------------------------------------------------------

Published in the National Library of

Wales Journal Vol XV (Winter 1967)CONTENTS

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas1. INTRODUCTION TO EDWARD THOMAS

'No one cares less than I,

Nobody knows but God,

Whether I am destined to lie

Under a foreign clod...'

......(No One Cares Less than I)

......Edward Thomas, 26th May 1916

Edward Thomas in 1913. Today we see Edward Thomas (1878-1917) as a quintessential English poet, though by parentage at least he was Welsh, whose father from Tredegar and mother from Newport had met and married in London where Thomas was born. But upbringing, not ancestry, finally decides your nationality and English poetry rightly claims Edward Thomas as its own. Born in London on 3rd March 1878, the eldest of six brothers, it was there he grew up, later being educated at Oxford University before living most of what remained of his short life in Kent and Hampshire. His place in the pantheon of twentieth century English poets is assured with such well-loved poems as Adlestrop, Tall Nettles, There Was a Time, At the Team's Head-Brass, The Manor Farm, Out in the Dark, Rain, Old Man, Lights Out and perhaps that darkest of English poems, The Other.

Although a professional writer all his adult life, he became a poet almost by chance at the late age of 37, in the last two years of his life. Until then he was what is rather dismissively described as a 'hack' writer, turning his hand to anything and everything in order to provide for his wife and young family. He published travel books, literary criticism, biography, fiction and sketches; he edited anthologies, and wrote well over a million words in book reviews alone. As the critic Geoffrey Grigson rather acidly puts it, Thomas was:

"caught in the multiplicity of a trap, personal, marital and historical ... poor, difficult, delicately balanced ... married too young, with too much early responsibility, honest, talented, yet not enormously so, caught in the more than usually dishonest, sticky artificiality of letters in late Victorian and Edwardian England."

If any of his prose works are read today, so completely has his poetry eclipsed them in reputation, it is a very few of his many travel books, often written after a long walking tour of the countryside; works such as Beautiful Wales (1905), The Heart of England (1906), The South Country (1909), In Pursuit of Spring (1914). It was the American poet Robert Frost who persuaded Edward Thomas that in this last work he was already writing poetry and it would take a minimum of adjustment to turn it into verse. Thomas wisely took Frost's advice and posterity is profoundly grateful that he did. He may have written poetry for only the last two years of his life, before a shell blast cut his life short in the first hour of the Battle of Arras on April 9th 1917, but the body of work he left behind, though small, is as they say, beautifully formed. Between December 1914 and his death two years and four months later he wrote 144 poems and is increasingly regarded as among the finest and most influential British poets of the time.

He was 39 when he died and already old to have enlisted into the army less than two years earlier in July 1915, but some demon in his psyche seems to have driven him to volunteer for the front even when, because of his age, he wasn't compelled to. He enlisted as a private in the Artists' Rifles (a Territorial corps) as early as July 1915, but didn't volunteer for active service in France until February 1917, by which time he had obtained a commission in the Royal Artillery as a second lieutenant. (When asked why he had transferred to the artillery, he characteristically replied that his widow would get a better pension.) Only two months were to remain for him while, in the words of a poet from the next world conflagration, he "brooded long/On death and beauty - till a bullet stopped his song". (All Day It Has Rained, Alun Lewis, 1915 - 1944).

Note on the Artists' Rifles:

The 38th Middlesex (Artists') Rifle Volunteers was formed in 1860 by Edward Sterling. At first the regiment largely consisted of painters, sculptors, engravers, musicians, architects and actors. Over the years several outstanding artists served in the regiment including Everett Millais, G F Watts, Holman Hunt and William Morris. During the First World War the regiment included Barnes Wallis (the later inventor of the 'bouncing bomb'), Edward Thomas, Paul Nash and John Nash. The Artists' Rifle Volunteers were disbanded in 1945, but were combined with other elements to form the 21st Regiment Special Air Service (Volunteers).The Poetry

Edward Thomas was, from the evidence of his wife and letters, a deeply melancholic man. But for all his troubled nature he also attracted people to him by his charm and seriousness and he made many deep and lasting friendships throughout his life. The Celts have a habit of claiming melancholy for themselves, curiously so, since this unhappy cast of mind is thoroughly universal and belongs to no one race or nationality. Wherever Thomas's melancholia originates (today it is more likely to be diagnosed as depression, and he suffered several breakdowns brought on by the unrelenting pressure of work and financial anxiety), his poetry is shot through with shafts of light and shade, often both together in the same poem, as just these few lines show:No garden appears, no path…..

Only an avenue, dark, nameless, without end.

..........Old Man (December 1914)This is my grief. That land,

My home, I have never seen;

No traveller tells of it,

However far he has been.

..........Home (February 1915)Beauty would still be far off

However many hills I climbed over;

Peace would still be farther.

..........Health (April 1915)And shall I ask ... what I can have meant

By happiness? ... Or shall I perhaps know

That I was happy oft and oft before,

Awhile forgetting how I am fast pent,

How dreary swift, with naught to travel to,

Is time? I cannot bite the day to the core.

..........The Glory (May 1915)... Like me who have no love which this wild rain

Has not dissolved except the love of death,

If love it be for what is perfect and

Cannot the tempest tells me, disappoint.

..........Rain (January 1916)Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance.

..........Roads, January 1916There is not any book

Or face of dearest look

That I would not turn from now

To go into the unknown

I must enter, and leave, alone,

I know not how.

The tall forest towers;

Its cloudy foliage lowers

Ahead, shelf above shelf;

In silence I hear and obey

That I may lose my way

And myself.

..........Lights Out (November 1916)This polarity in his work, the play of light and shade together, only enhances his appeal to today's more attentive reading public, a welcome recognition after some fifty years of neglect following his death. And if the dark side of Thomas's mind draws critics and academics to his work, the poems about the English countryside are where his popular reputation lies. This can lead to confusion about where to 'place' Edward Thomas and he is variously described a nature poet, a 'Georgian', a modernist and a war poet, this last label despite the fact he wrote no poems after he volunteered for action in France in February 1917.

But labels are for the convenience of journalists and academics, not poetry lovers. Early admirers of Edward Thomas's poetry included Walter de la Mare and W. H. Auden and leading contemporary poets such as Ted Hughes, Philip Larkin, Seamus Heaney and R. S. Thomas have acknowledged their debt to him. The literary scholar F. R. Leavis singled him out as "an original poet of rare quality" as far back as 1932 and more recently Andrew Motion, the current Poet Laureate, has nominated 'Old Man' by Edward Thomas as his favourite poem "because it so brilliantly proves, as do all his poems, that you can speak softly and yet let your voice carry a long way". Edward Thomas is commemorated in Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey, by pictorial windows in two parish churches, and by a sarsen boulder memorial on the hillside above Steep in Hampshire, his home at the time of his death.

The poems remain as much alive now as when they were written, quietly yet surely capturing the essence of the English countryside which Edward Thomas knew through all his senses. He is the least rhetorical of poets, modestly sharing his experiences with his readers and leading them into the reality behind the words until, for instance, we too can almost hear "all the birds of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire" (Adlestrop).

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas2. EDWARD THOMAS AND AMMANFORD

Thomas's Welsh parentage seems to have drawn him frequently to Wales and particularly to Pontardulais and Ammanford where he and his family had strong connections. It was in Ammanford he made the acquaintance of Watcyn Wyn (Watkin Hezekiah Williams), the founder and headmaster of Gwynfryn College, situated on what is now named College Street after the school. Three of Edward Thomas's brothers came to Ammanford to study at Gwynfryn College and the entire family made occasional visits here. [To see a brief biography of Watcyn Wyn click HERE]

But it was with John Jenkins, Watcyn Wyn's successor as headmaster on his death in 1905, that he enjoyed a much deeper friendship, lasting 20 years from the time they first met in 1897 to Thomas's death in 1917. (The custom of Welsh language poets is to take a bardic name and John Jenkins is better known by his chosen name of 'Gwili', after a river in his native Pontardulais, just seven miles downstream from Ammanford.)

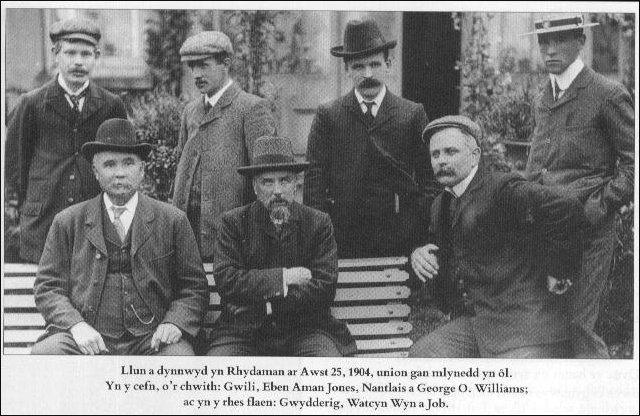

Photo: A gathering of poets and preachers in Ammanford in 1904. Close friend of Edward Thomas, John Jenkins (Gwili), is first left, top row. Poet Watcyn Wyn (in the centre of the bottom row) was headmaster of the Ammanford school that three of Edward Thomas's brothers attended (a biography of Watcyn Wyn can be found in the 'People' section of the website, or click HERE). Methodist preacher, poet and hymnist Nantlais is top row, third from left (a biography of Nantlais can be found in the 'People' section of the website, or click HERE). The text below the photo reads: "Picture taken in Ammanford on August 25th 1904, a hundred years ago. In the back, from left: Gwili, Eben Aman Jones, Nantlais and George O. Williams; and in the front row: Gwydderig, Watcyn Wyn and Job." Photo from Summer 2004 edition of Barddas (Poetry).. The following article, published in the National Library of Wales Journal in 1967, was written by Elis Jenkins, a nephew of Gwili's, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Thomas's death in action in World War One in 1917. We recognise the place names mentioned in the article because they are all to be found in the Amman, Llwchwr and Towy valleys. The author of this website can even claim to have walked most of the places Edward Thomas and his friend Gwili explored, and that same countryside, once you make the small effort to get away from today's traffic-choked roads, still retains its beauty and power to calm they saw a hundred years ago.

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas----------------------------------------------------------------FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF

EDWARD THOMAS (1878-1917)

'SOME OF HIS WELSH FRIENDS'----------------------------------------------------------------

Published in the National Library of Wales Journal

Vol XV (Winter 1967)

EDWARD Thomas was killed near Arras on Easter Monday, 1917, which in that year was the 9th of April. At dawn on the first day of the tremendous British attack on the Hindenburg Line, he had just reached an advance observation post from which he was directing the fire of his battery, when a shell burst near him. Only a few days earlier he had lovingly described in a letter the birds in No Man's Land that had survived the holocaust of this terrible spring offensive.

At a similar stage of the Second World War, another Welsh poet, Alun Lewis, was in camp in Hampshire, not far from the roughly-hewn stone memorial to Edward Thomas on the Shoulder o' Mutton Hill. In one of his most moving poems, the one beginning, 'All day it has rained', Lewis pays homage to his fellow-countryman who had lived in a nearby cottage a generation before:

..."And I can remember nothing dearer or more to my heart

...Than the children I watched in the Woods on Saturday

...Shaking down burning chestnuts for the schoolyard's merry play

...Or the shaggy patient dog who followed me

...Through Sheet and Steep and up the wooded scree

...To the Shoulder o' Mutton where Edward Thomas brooded long

...On death arid beauty till a bullet stopped his song."Some years ago, my old friend R. L. Watson, who was compiling a symposium to he called Memories of Edward Thomas, would not consider including this passage because of the inaccurate bullet-reference in the last line. Yet I am sure Watson would have allowed my designation of 'fellow-countryman', even though Edward Thomas was a Londoner. He always thought of himself as Welsh, his wife Helen thought of him as Welsh; indeed in my copy of As It Was, Helen Thomas's beautiful account of their early years together, she has written on the fly-leaf, 'Wales, the native land of Edward Thomas, was very dear to him'. One of his closest friends, J. W. Haines, wrote a monograph which he called 'Edward Thomas, a Welsh poet'. The Lambeth-born son of Glamorgan and Gwent parents gave his own three children Welsh names, sang them Welsh songs, read them Welsh legends. Occasionally, when he could afford it, he took them with him to Wales, which he tramped more thoroughly and more often than any other region.

Edward Thomas was the eldest of six Thomas boys, all of whom at various times, either singly or in greater numbers, returned to the land of their father, at first staying with relatives. 'Edwy' (as Edward was called in the family) first stayed with Philip Treharne Thomas at Tynybonau, a part of Pontardulais; and it was there that he first met my uncle, John Jenkins, better known later as the bard Gwili, a gifted poet who became one of his country's foremost theologians and a Doctor in Literature of the University of Oxford. Edward's reconnaissance of the Amman and Llwchwr Valleys was the prelude to an invasion by the other young Thomases, for soon afterwards, three brothers, Reggie, Julian and Oscar, came to Arnmanford to attend the Gwynfryn School, a small 'Academy' notable in South Wales not only for its experimental work in adult education, but for the wit of its bardic principal, Watcyn Williams, whom all Welshmen knew as Watcyn Wyn. Edward seems to have spent much time with Gwili, not only out of doors, but in the kitchen of Gwili's cottage at Hendy, where he was wont to fondle the old brass candlesticks and blow the fire with the studded bellows. Later, when he moved to Rose Acre Cottage, his first country home after marriage, he bought a similar pair of candlesticks and a bellows from a second-hand dealer.

After the last War, I tried to obtain other recollections of these Welsh visits in the early years of this century, but was only partially successful, for any surviving contemporaries would then have been septuagenarians; nevertheless appeals in several newspapers brought two or three memories of brief encounters. One, from Carey Morris, the Welsh artist who lived in retirement in Llandeilo, recalled such a meeting about sixty years ago, when Thomas had walked from Ammanford with the late Tom Mathews. When the latter asked Mr. Morris why he preferred to paint geese in Cornwall to swans on the Towy, they noted with interest Edward Thomas's quick understanding of the difficulties confronting the native artist. J. D. Williams, editor of the Cambria Daily Leader between the Wars, who later was accidentally killed while mountain-climbing in North Wales, after reading of the poet's despondency and self-mistrust, described a walk with him in the Carmarthenshire hills.

'The black mood must have been upon him, for all day there was little said by either of us. On the mountains, it is not natural to talk much; but Edward Thomas had a gift of silence when he chose to exercise it.'

The attempt to trace members of the South Wales branch of the family was not more fruitful. As Nurse Thomas of Pontardulais, the widow of one of them, said, 'The Thomases are a shy lot'. Miss Gwen John's interesting reminiscences and Nest Bradney's loving account of the friendship of her father with Edward Thomas came independently of a public request for information, as their links with Edward Thomas were already well-known.

Helen Noble aged 21 in 1899, the year she married Edward Thomas. Just before the Second World War, Gwili's sisters recalled the young man they knew in those far-off days. The outward person they described is now familiar enough: the spare frame, the soft, low voice, the diffident manner, the quiet companion who seldom spoke unless addressed directly. On the fly-leaf of my copy of Rose Acre Papers (1904), there is a neat inscription, 'To Gwili, wishing the book were better,' which epitomised the excessive modesty that never left him, but which increased to a climax of complete self-depreciation in that harrowing letter to Harold Monro in 1915, offering the poems which were, of course, returned. Yet the third of the four little untitled essays which he wished better, the one reprinted in 1910 as 'An Autumn House', can stand alongside the best since Lamb. Helen Thomas, too, seemed to be infected, especially in her self-portrait of the 'plain woman' in As It Was, for the sisters remembered the fine features of the young wife, her beautiful brown hair and eyes, and her elegant clothes.

There was a lighter side in those early days in Wales, as when the two lads, Edward and Gwili, used to chalk on the carts outside the house of Bonnell, the local haulier, the more amusing Caradog-Evans solecisms which the latter had committed in his attempt to turn Welsh phrases too literally into the stranger's English. One they recalled was 'I can speak the two spokes'. [See Note 1 below] Then there was the occasion when, after tramping over the Black Mountains to Dryslwyn, the two called at a farm for refreshment. Edward attempted a conversation with the Welsh dairymaid, who turned to Gwili and asked in Welsh, 'What's this Cockney trying to say?' But more recognisable to us was their recollection of the anger in Edward's face as he leapt towards a friend who was about to kill a snake; or the expression of ecstasy on his countenance as he looked out from the church of Llandeilo Tal-y-bont at a great thunderstorm, with the forked lightning streaking to earth around him. [for Llandeilo Tal-y-bont see Note (2) below.]

Between the visits there was much corresponding. In one letter from Rose Acre Cottage, he mentions his old Oxford tutor (Sir) Owen M. Edwards, best-loved Welshman of his time.

'We have moved away from Wales, but we do not think of it the less. I am reading O.M.E.'s 'Wales". At every page I am filled with admiration of its author and love of his subject. Possibly I shall next year publish a volume called 'Horae Solitariae,' and I hope to be allowed to dedicate it to O.M.E. ... I owe you a letter, and this is no payment of my debt ... You would excuse my silence, I am sure, if you knew the anxious poverty in which I have been living for some months. Whether the New Year brings a change or not, I shall try to write.'

These disjointed impressions, if they do not add much to our understanding of the man, are at any rate gossipy reminiscences which their subject would have enjoyed, as he loved and enjoyed everything Welsh. Although Gwili had been persuaded to write a memoir, he did not publish anything beyond a two-column article in Welsh; but his daughter, the late Nest Bradney, had access to the letters preserved by her father, as well as a fund of family memories, from which she drew freely. She reminded me that Edward Thomas dedicated his book on Lafcadio Hearn to the Bard Gwili. Underneath the printed dedication, in the copy which her father passed on to her, with other treasured volumes of Edward Thomas's work, was written in the poet's hand, 'From Edward Thomas, 27. ix. 12'. Their friendship by that time was fifteen years old. Sometimes there were long gaps when they did not meet at all, nor even write, and then, of a sudden, the friendship would burst into a warm flowering all over again, with a rapid crossfire of correspondence; or a visit to Wales, when the two of them would walk in the Swansea Valley talking like mad in the language understood of poets and thinkers.

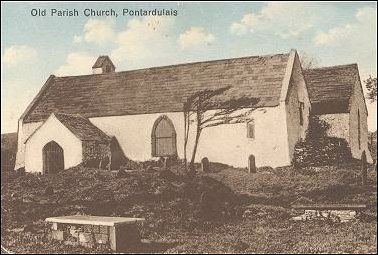

Edward Thomas and Gwili first met in the Autumn of 1897, when Edward was staying with relatives in the neighbourhood of Swansea. On a warm September day that year, my grandmother prepared a tea party in Gwili Cottage for Gwili and Ben Bowen (a brilliant Welsh poet who died young, and uncle of Sir Ben Bowen Thomas), and the new friend who was known to be a writer, too, Edward Thomas. They talked about everything, but mostly about poets and poetry, and during the week that followed Edward and Gwili were together a good deal, walking in the countryside around Pontardulais. One day they walked to the top of the mountain and read 'Ships that pass in the night' all through. Edward grew to love Gwili Cottage, particularly the kitchen, with its old brass candlesticks and the studded bellows. Two of these candlesticks, tiny ones, my Aunt Lizzie told me were used by the family long ago, before they became non-conformists presumably, to take to the Plygain Service at five o'clock on Christmas morning. (An old Welshman Nest knew used to say all the light you get in Church is what you take in with you; and it was literally true in the old days when people brought their own candles.) This custom has almost died out. In Beautiful Wales, there is a description of Pontardulais and the little old church which evidently made an impression on Edward Thomas. He says:

'When it reaches the next village, the river is so yellow and poisonous that only in great floods dare the salmon come up. There with two other rivers it makes a noble estuary, and at the head of the estuary and in the village that commands it, the old and the new seem to be at strife. On the one hand are the magnificent furnaces; the black wet roads ... On the other hand, there is the great water, but as it were a white area of the sea, thrust into the land to preserve the influence of the sea. Close to the village stands a wooded barrow and an ancient camp; and there are long flat marshes where sea-gulls waver and mew; and a cluster of oaks so wind-worn that when a west wind comes it seems to come from them as they wave their haggish arms; and a little desolate white church and white-walled graveyard, which on December evenings will shine and seem to be the only things at one with the foamy water and the dim sky, before the storm; and when the storm comes, the church is gathered up into its breast and is part of it .... [The church is Llandeilo Tal-y-Bont again - see photo below and also Note (2) below].

The fine medieaval church of LlandeiloTalybont in Hendy, Pontardulais, now being re-assembled in the Welsh Folk Museum, St Fagans. That's the estuary at Pontardulais all right, not Llanstephan or Laugharne or anywhere else. Nest had seen that river and the little white church too many times from Gwili Fryn, where Gwili's half-sister Catherine lived, to mistake its description in Beautiful Wales, for Edward Thomas was shy of naming exact places.

Gwili Cottage was on a tributary of the big river, and the little stream, the Gwili, ran at the bottom of the garden. It was there that my uncle early learnt to tickle the trout and to swim almost as well as they. It was by swimming in the big river, its water yellowed by vitriol from the works, that he impaired his eyesight, and it was there that he was once nearly drowned in the cross-currents of an incoming tide. He loved the river in all its moods, and all through his life. Edward understood him well, and it is Gwili he describes in this extract from 'Digressions on Fish and Fishing', in Horae Solitariae.

'And another reverend angler I knew in Wales, whom I may not forget. There was a singular finish and cadence about the courses of his life. He himself would call it modestly 'a beautiful blank, like a fair sheet of paper unsoiled by art.' He was born in a cottage whose wall rose sheer from a bank where a little river died in the surges of a tumultuous estuary. His boyhood and manhood were spent partly in another cottage whose garden slopes to the same river, but chiefly in the river itself, he being a famous truant in those days. When he came to the years that bring ennui and the philosophic mind, he wrote verse; and when, according to the happy Cambrian custom, he used a bardic name, he took it from the stream whose sound was always in his ears, and which - being no 'swan', but just a merry sandpiper - he trained to suit the dainty melody of his verses. In one of his lyrics - I think they are his; anyhow, his frequent repetition made them his own - he put his own wild heart into the cry of the river, as it turned and seemed in places to lose its way, ever with its heart set towards the sea: 'The sea! the sea evermore'. He was, he said, no more than Carlyle's minion, 'Far from the maine-sea deepe!' Yet his soul went out to the sea, to the great matters of the world, even giving these reality and colour by references to the little river and its copses, that furnished his house of thought with the metaphors by which he lived. He was one of the few genuine fishing philosophers I ever knew.'

At the time of the first meeting of Gwili and Edward Thomas, Gwili was still in his twenties, was in great demand all over the Principality as a popular young Baptist preacher, and travelling here and there, preaching, lecturing, attending Eisteddfodau, and continually writing poetry. Both he and Edward Thomas may have had a good measure of confidence in themselves at this period, not knowing that bleak times were ahead for both of them.

Nest may have strayed a long way from the parlour of Gwili Cottage on that September afternoon of 1897, but she wanted to describe for English readers this friend of Edward Thomas's whom he mostly referred to as 'The Bard' or 'The Parson'.

Anyone who knows Wales and reads Beautiful Wales cannot fail to be struck by the author's penetrating knowledge of the country and its spirit, and its people's temperament. I am sure that the key to much that was inward and difficult of perception in the Celtic heart was supplied for Edward by Gwili. Certainly he was able to bridge one serious difficulty, Edward's ignorance of the language, and this, for anyone who wishes to understand the Welsh people, is a serious difficulty indeed. From some of the letters that Gwili kept, it is clear that Edward used to consult him about Iolo and Borrow, and the Mabinogion, and the Welsh metrical system. On the backs of one or two envelopes were jottings about the rules of Welsh poetry, a complex system which attracted the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins. In his Introduction to the Poems of John Dyer, Edward Thomas thanks Mr. John Jenkins (Gwili) for answers to his enquiries concerning the poet; and mention of John Dyer reminded Nest of a tale her father used to tell about a wonderful moonlight walk he took with Edward Thomas and Thomas Seccombe to Golden Grove, then a country seat near Llandeilo in the Vale of Towy, the loveliest and the softest countryside in Wales. As they walked through the copses they talked about Jeremy Taylor, and as they climbed to Dryslwyn Castle and wandered over Grongar Hill, they spoke of the Bard of the Fleece and the literary associations of the Vale. It was probably this trip which interested Edward Thomas in John Dyer in the first place. Thomas Seccombe was so charmed with it all that he came back in the Summer with his bicycle and visited Carmarthen and Llandeilo, and met them both again in Carreg Cennen Castle, that glorious ruin on its limestone crag, complete with underground passage and a wishing well. That day at Carreg Cennen must have been a memorable one. Gwili was teasing Seccombe for remembering nothing of the connexion of Dyer and Taylor with the lovely vale he had just passed through, and Thomas and Seccombe were joking about 'The Parson'.

These days in high summer in Carmarthenshire, whether in Pontardulais or near Ammanford, must have been very happy ones. The friendship between the two men must somehow have become localised, built into the fabric of Carmarthenshire. Though Gwili loved Oxford, and though they mentioned the place in their letters, it had become for Edward Thomas the echo of a past experience by the time Gwili reached it after graduating at Bangor. Gwili, unlike Edward, was in the middle thirties when he went up to Jesus College, and Edward had left the University some years before. Nor could they often arrange a meeting in London either. But in Wales things were different. A place they both loved was Llanedi, a quiet stretch of hillside beyond Pontardulais, far enough from the furnaces to breathe a delicious pastoral grace, and yet within sight of the estuary and its silver shallows. Here was a tiny whitewashed chapel, one of the very earliest Non-conformist causes, embedded in the hillside, beautifully proportioned in its miniature way. Here they both mused among the bluebells, and here Gwili and my father sleep their last sleep. Another favourite walking place was Llyn-y-Fan Fach, among the deserted hills with their bleached grass and perpetually moving shadows of clouds rising in the wide sky. Once, when Nest was on a walk to Llyn y Fan with her father, he told her that Edward broke into a run when they were still a quarter of a mile from the lake, and as he ran he scattered his garments here and there, to plunge finally into the clear amber depths of the lake. I wonder whether he thought he would be the first to see the Maiden of the Lake, who was won by the shepherd boy seven centuries ago. And then again, they would wander to Llyn Llech Owen, above Ammanford and the Towy, another lake which has its legend, that of a man who watered his horse at a well and forgot to replace the stone. Edward Thomas must have had enormous physical energy, or else he must have found these walks reward enough for the expenditure of so much of it. Among the letters to Gwili was a yellowing post-card, with an almost indecipherable post-mark (Nest thought it was 1914), addressed from Swansea, which said:

'If it is fine on Monday I could cycle over to Ammanford in the morning, arriving about 12, and we could have a walk. I should or ought to start back so as to do part of the way before lighting up, as the roads are awkward in places. Let me know if this suits. If it turns wet, we'll give it up.'

Edward Thomas in 1900 with his son Mervyn. Swansea to Ammanford and back on a 1914 bicycle, and a walk sandwiched in between must have been quite a feat! In 1914, he stayed in Ammanford village for a holiday. Gwili had been living there for some years, having taken over Gwynfryn from Watcyn Wyn as a school for grown-up men who wished to prepare themselves for the University or for the ministry. Gwili was about to go to America on a preaching and lecture tour, and wanted Edward to join him, but though the idea was attractive to him he could not contemplate it as a lecturer. But Edward came to Ammanford on his much-looked-forward-to visit. Two of his children came, Mervyn and Bronwen. Special preparations were to be made at the lodgings, brown bread was to be got in, and it was to be baked in slices very hard in the oven. There were to be some bananas and dates if possible, and the tail piece of the letter asked for very fat bacon, the fattest in the land. He was depressed though, for things were going badly with his books. 'There is nothing nowadays equal to nutting by the Gwili', he says at the end of the letter. It was during this holiday, probably the last time they ever met, that an incident occurred that grieved Gwili deeply, and which no doubt he forgave in after years, knowing Edward's proud spirit and his great bitterness of mind at that time. They were walking along the railway line somewhere near Ammanford, Bronwen toddling by her father's side. When the time came to part, Gwili, as is still the custom in Wales, gave Bronwen a silver coin. To his amazement and distress, Edward seized it from the child and threw it violently down. 'I cannot remember what his words were, though my father once told me', said Nest, 'but I can hear clearly the clash and jar of the coin on the metal of the railway'. That was the last time they were together. Edward Thomas's death soon afterwards was deeply felt by Gwili, and he wrote a poem to the memory of his friend, the elegy 'To Edward Eastaway'. [This elegy is reprinted in Section 6 below.]

The late Gwen John, one of Swansea's great characters till her death about eight years ago, has also recorded her memories. Just before Helen Thomas visited Swansea in 1957 to give a reading of her husband's poems, Gwen John sent me these reminiscences.

'It may seem a far cry from a Welsh grandmother to Edward Thomas, but inasmuch as he loved all things Welsh, it is not inappropriate. I had a wonderful Welsh grandmother born and bred in a farmhouse on the mountains above Hirwaun, in South Wales. In a farm nearby lived the grandmother of a man who had risen to fame in letters and law, Professor John Hartman Morgan, K.C. - later Brigadier General Morgan - close friend of the late John Morley and Thomas Hardy. 'Macws' was the name of J. H. Morgan's grandmother, and it is said that Macws and my grandmother used to feather their chickens till late into the night so that they might read their Bible during the day. My uncle, Mr. John Williams, Waunwen, Swansea, a schoolmaster of that town, developed a great interest in Morgan, who in the nineties was a student at Cardiff and was later proceeding to Balliol, where my uncle used to visit him. Morgan was in touch with many brilliant men of his day, and among his friends my uncle was destined to meet Edward Thomas, who was at Lincoln College. Their close friendship lasted till his death.

......Edward Thomas was soon visiting us quite frequently, sometimes with his wife, who for her charm and individuality is worthy of a book of reminiscences to herself. I will confess that the only men who have ever awed me into silence were these two visitors of my uncle's, J. H. Morgan and Edward Thomas: Morgan by his brilliant volubility, and Thomas by his majestic silence. The latter never spoke unless he had something worth saying; nevertheless, it gave me a sense of inferiority which made me timorous of hazarding trivial remarks. Edward Thomas loved the simple things of life, but he seemed to be enjoying them in an inner temple where it was sacrilege to intrude. He must have been rather poor in those struggling days, but so rich was his personality that you could never connect poverty with him. Even his clothes took upon themselves a rich personality. Striding down the High Street of our town or walking abstractedly by my aunt, he made me think of Gulliver and Tennyson combined: Gulliver-like in his towering above the world around him, Tennyson-like in a certain soft texture of dress which he affected, and a certain dreamy aloofness. But there was also a leonine expression of strength and even cynicism in the face, that was not Tennysonian. I rarely saw him smile, nor heard him laugh, yet he never looked unhappy. His care of his very good clothes might have made one suspect him of dandyism, if knowledge of facts had not revealed that he had to make them last through so much arduous walking and weather.

......He used to be taken to all the intimate haunts of my uncle and aunt, to visit all our Welsh relations, to a homely Welsh tea somewhere on our lovely sea-coast, and even to a Welsh chapel. On all these occasions he seemed like a very fine Welsh sheep-dog, very appreciative, but led all the same. He really became himself when he took to the hills, in a tremendous fawn coat, and the biggest boots I think I have ever seen. Then he would wander off to the Van Pools, Breconshire, and arrive by unknown mountain paths at Ammanford in Carmarthenshire, where he would hear amusing stories from the poet Watcyn Wyn. This pleased him much. The next thing we would hear was that he was stranded somewhere on a Sunday, but eventually he would arrive home, and take to brooding over our kitchen fire, as if he had brought back with him the ingle of a Welsh farmhouse. The boots would be in the oven for a few days, and the coat by the fire drying. He was the despair of my aunt, who wanted the fireplace to cook, in order to charm him with Welsh delicacies (for which he had a great liking, particularly cockles). On one occasion his wife came with him, a sweet brown-haired lady with a fund of stories of her early home, which was always filled with the rising literary men of the late nineteenth century, for Helen Thomas was the daughter of James Ashcroft Noble. Richard le Gallienne she described as coming to her father's house in a flowing tie, and carrying a bouquet of rhododendrons. She had made herself very domesticated in order to battle with the difficulties of a restricted income, and delighted in my aunt's home-made bread and wholesome cooking. She also shared her husband's elegance of appearance. I still remember her peacock-blue dress as well as I remember Edward's fawn coat. He nearly always wore fawn. It matched his hair.

......Edward Thomas could be capricious. He and Mrs. Thomas were invited to dinner by an old Oxford friend living in the neighbourhood. Mrs. Thomas, in the way of women, said she would go and then that she wouldn't, and Edward said, 'You shan't'. Although he had been to a smart dinner, when he came home he wanted some of Aunty's nice broth. Edward Thomas and his wife, my uncle and I, and a friend, went for a day to the beautiful falls near Pont Nedd Fechan. I remember a delicious meal of ham and eggs in the Angel, eaten as silently as if it were a religious rite. A wonderful hound followed us to the falls, and Edward Thomas fed it on blackberries. I remember perilious crossings of streams, which he strode across like a Colossus - a happy day, in which he imbued all the party with that spirit of his so at one with nature. On our return, I ventured to ask him to write in my album, and in his exquisite handwriting, he wrote, 'Words, not deeds'. I once told him that I had read the whole of Wordsworth's 'Excursion', and he told me that I should have the fact recorded on my tombstone. When I showed him a description of a holiday in Normandy, he said that in his opinion I would make an excellent writer of guide-books!

......He revealed a stoicism which was in keeping with a certain hardness in his composition. He said that whenever he looked at a man's face, he could see the skull behind it, a remarkable revelation of his gift of looking right into things. This was characteristic of him, so sincere and so scornful of sham. He used the same rapier-like judgment about Swansea, which, in an article in the English Review he called 'a dirty village'. How the critics raved! But he knew what he meant, for had he not prayed for wet weather in order to escape the fumes of coppersmoke that invaded the town in fine autumn weather: and further, was not our homely village spirit one of the chief charms of our town?

......Great was his disgust when he visited us in our new house in 1914 to find that his beloved brass candlesticks had been removed from kitchen to lounge. One day, when he was looking for copy for his article on Swansea, I asked him where he had been. His reply was 'to Shelley Crescent'. Shelley Crescent was a very ordinary row of houses nearby, and in his reply you could feel the incongruity of naming the street thus.

......Just before he was killed 1 knitted him a pair of socks, He asked that they should be very large, and wrote back a short note to say that they were 'just right!' Among my most poignant memories was the news of his death. One morning, I said casually to my uncle, 'You have not beard from Edward Thomas lately? He did not reply, but later thrust into my hand the letter from his wife containing the news. I have in my possession two letters to my uncle which were among the last letters he ever wrote. They reveal his mood in the face of war- all anxiety for his family but a desire for actiyity and achievement.

......In 1923, I visited his Oxford rooms. The first term he had been forced into luxury by circumstances of accommodation, but his last room at Lincoln was a simple affair at the top of a tortuous staircase; yet I can imagine him happier in the less pretentious quarters. The Master of Lincoln spoke of him tenderly, and said that 'he had left books to the College'.So much for the Welsh friends. To discover what Wales meant to Edward Thomas the reader can turn to his writings, where references to the countryside of Wales, its People and its lore, are frequent enough. Not often in our literature has an ear been tuned more finely to the music of place names than in such passage as this: 'I will please myself and the discerning reader by repeating the names of a few of the places - Llangollen. Aberglasnyn, Bettws-y-Coed, Curig, Colwyn, Tintern, Bethesda, Llanrhaiadr. Llanynys, Tenby (a beautiful flower with a beetle in it), Mostyn, the Mumbles, Harlech, Towyn, Aberdovey - I have read many lyrics worse than that inventory.' Or again, from Beautiful Wales where he describes the 'Shy streams, the deserted pathways of the early gods, the Dulais and Marlais and Gwili and Amman and Cennen and Gwenlais and Gwendraeth Fawr and Sawdde and Sawdde Fechan and Twrch'. [see Note (3) below.] He did the same for English villages in his poem:

'If I should ever by chance grow rich,

I'd buy Codham, Cockridden and Childerditch.

Poses, Pyrgo and Lapwater.'His death at the age of 39 was a loss that even the anthologies are beginning to recognise.

ELIS JENKINS

NeathNOTE. It is sad to record that Helen Thomas, the poet's widow, died a few days after the fiftieth anniversary of her husband's death in action. W.E.J.

The above article was first published as 'FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF EDWARD THOMAS (1878-1917) SOME OF HIS WELSH FRIENDS' in the National Library of Wales Journal, Vol XV (Winter 1967). I am indebted to Dr Huw Walters of the National Library of Wales in Aberystwyth for drawing my attention to this article.

Notes:

(1) Caradoc Evans (1878 - 1945), Welsh short story writer and novelist, much of whose work was set in his native Cardiganshire. Although a first language Welsh speaker he chose to write in English, often giving his characters dialogue which imitated the vocabulary, grammatical order and syntax of Welsh. The resultant English was often a grotesque parody of speech, satirizing what Evans saw as the primitive thought processes of the Cardiganshire peasantry. Examples of 'Caradoc-speak' are: "mouth you like this to them", "why for do you not reply to me", "people church are down there", "what is your want? and "the Big Man" (i.e. God).

......Caradoc Evans was not popular at home with the Welsh establishment, especially chapel elders whom he attacked in his fiction for their avarice, narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy. In contrast, he was received with glee by many English readers who were happy to have their worst prejudices about the Welsh seemingly confirmed. He was for a while probably the most hated writer in Wales - Lloyd George was just one of many who denounced his books - and is still treated with suspicion in some quarters. Whatever the opinions about his work, he was undeniably one of the founding fathers of modern Anglo-Welsh literature. Gwyn Jones has written of Caradoc's impact "the war-horn was blown, the gauntlet thrown down, the gates of the temple shattered. The Anglo-Welsh had arrived ... with the maximum of offence and the maximum of effect."(2) Llandeilo Tal-y-bont is - or at least was - a fine medieval church on the marshy banks of the estuarine Loughor in Hendy, Pontardulais, and was used for worship during the summer months until fairly recently. The ghosts of Edward Thomas and Gwili, if they are re-visiting Pontardulais today, will not find this church in its accustomed spot beside the river Loughor (or Llwchwr in Welsh) and would be somewhat puzzled instead to find it is now in a museum. In 1997 it was dismantled, each stone carefully numbered, and transported to the Welsh Folk Museum in St Fagans where it has been re-assembled in something like its original condition Its history, with details of the restoration, can be found on the website of the Museum of Welsh Life, St Fagans, on:

http://www.nmgw.ac.uk/www.php/198/(3) Rivers of the Amman and nearby valleys. Dylan Thomas was to make a similar list of Welsh rivers in Under Milk Wood thirty five years after the death of Edward Thomas:

"By Sawdde, Senny, Dovey, Dee,

Edw, Eden, Aled, all,

Taff and Towy, broad and free,

Llyfnant with its waterfall,Claerwen, Cleddau, Dulais, Duw,

Ely, Gwili, Ogwr, Nedd ..."(Under Milk Wood (1953), The Reverend Eli Jenkins' Poem to Morning)

Both poets mention the rivers Sawdde, Dulais and Gwili, which leads one to suppose that Dylan Thomas knew Beautiful Wales, and of course Marlais was also Dylan Thomas's middle name. There are several rivers and streams by that name in Wales: the Marlais Edward Thomas mentions is the tributary of the Llwchwr flowing through Llandybie, while Dylan Thomas's name is probably after a Cardiganshire Marlais.

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas4. FURTHER MATERIAL

Website

A website devoted to Edward Thomas's life and work can be found on the Edward Thomas Fellowship site (http://www.Edward-thomas-fellowship.org.uk) which includes works by and about Edward Thomas plus the inevitable merchandise for sale. The website also includes selections from the poetry and prose.Poetry

Collected and Selected Poems of Edward Thomas are readily available at most bookshops and libraries. If you want to read them on the Internet then a comprehensive online selection of his poems can be found on: 'A Mirror of England':

(http://richmondreview.co.uk/library/thomas00.html)

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas5. JOHN JENKINS (GWILI)

The repository for Welsh people deemed to have become worthy of mention down the centuries is 'The Dictionary of Welsh Biography', published under the auspices of the Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion (cymmrodorion are fellows). The first edition, featuring the great and the good of Wales from the fifth century AD down to 1940, was published in 1959 and a supplement, with further notables down to 1970, followed in 2001. As we have heard much of John Jenkins, or Gwili, we should probably acquaint ourselves better with him, so here is his entry in the Dictionary:

Gwili in later years. JENKINS, JOHN (GWILI) (1872-1936), poet, theologian, and man of letters; born at Hendy, Pontardulais, Carmarthenshire, 8 Oct. 1872, son of John and Elizabeth Jenkins. He began preaching (with the Baptists) in 1891, and after a short period at Gwynfryn (Ammanford), the school kept by Watcyn Wyn (Watkin Hezekiah Williams), went in 1892 to Bangor and thence (1896) to University College, Cardiff; at both alike, preaching and poetry seemed to him more important than examinations. In 1897 began his friendship with (Philip) Edward Thomas. From 1897 to 1905 he assisted Watcyn Wyn at Gwynfryn, but in 1905 went up to Jesus College, Oxford; he graduated in the Theological School in 1908, and in later years won the degrees of B.Litt. (1917) and D.Litt. (1932). Throughout these years he never ceased to write poetry and prose, to preach, and to lecture. He felt no inclination to the pastorate (he refused three invitations), and although alert and thoughtful hearers highly valued his preaching, the excessive rapidity of his delivery, and his advanced views, precluded favour among the thoughtless or conservative. Nor, in poetry, was he successful in the strict metres; it is significant that all his successes in provincial eisteddfodau were gained in the free metres, and that his sole triumph in a national eisteddfod was the winning of the crown (at Merthyr Tydfil in 1901), which is given for work in free metres. After leaving Oxford he succeeded Watcyn Wyn at Gwynfryn; and in 1910 he married Mary E. Lewis (they had two daughters).

....In 1914 he was appointed editor of Seren Cymru [Star of Wales] - he edited it till 1927, and again from 1933 till his death. The war of 1914-19 put an end to his school, [ie Gwynfryn] and in 1917 he moved to Cardiff, at first as assistant to Thomas Powel, Professor of Welsh at University College, then as acting-professor sede vacante, and finally in charge of the Salesbury Library (1919); it was at Cardiff (1920) that he published his volume of English poems. His wanderings ceased when in 1923 he was appointed professor of New Testament Exegesis at the Baptist College (and also at University College) at Bangor. He did much work there, publishing in 1928 Arweiniad i'r Testament Newydd [Introduction to the New Testament], and in 1934 a volume of poetry, Caniadau [Songs], and editing Seren Gomer from 1930 to 1933. But quite certainly his magnum opus was his book on the history of theology in Wales, published in 1931 under the somewhat misleading title Hanfod Duw a Pherson Grist [The Essence of God and the Person of Christ], a piece of research in a field which hardly anyone before him (excepting maybe Owen Thomas,) had worked systematically. A list of his other writings in prose and verse, with a selection of his sermons, will be found in his biography by E. Cefni Jones, 1937. In 1931 he was elected archdruid. He died 16 May 1936 and was buried in the graveyard of the old Independent Meeting-house at Llanedy, Carms. Gwili was a jovial man, despite his disappointments, and a good companion; his little impracticalities only enhanced the affection of his friends.[E. Cefni Jones, Cofiant Gwili (above); Moore, Life and Letters of Edward Thomas, 168, 190, 274; personal acquaintance.]

The Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion was formed in 1751 by Lewis Morris (1702-65) and his brother Richard (1703-1796), and received a Royal Charter in 1951 on the occasion of its bicentenary. Their website is on: http://www.cymmrodorion1751.org.uk/ from which we learn: "Established for the encouragement of Literature, Science and the Arts as connected with Wales, the society continues to promote the practice and development of literature, the arts and sciences insofar as they are of special interest to Wales, the Welsh people and those interested in Wales."

The English equivalent of the 'Dictionary of Welsh Biography' is the massive 'Dictionary of National Biography' (DNB) published in 2004, though anyone wishing to display it on their bookshelves will first need to get hold of £7,500 and then shelves strong enough to hold its sixty encyclopedia-sized volumes. Its 50,000 double-column pages contain entries for 55,000 people and Gwili features in the DNB too:

Jenkins, John Gwili (1872-1936), poet and theologian, was born on 8 October 1872 at Hendy, Llanedi, Carmarthenshire, the fifth of nine children of John Jenkins (1829-1899), a tin-plate worker, and his wife, Elizabeth, née Davies (1842-1926). He attended the village school at Hendy, being engaged as a pupil teacher from 1887 to 1890, and then entered the Gwynfryn School, Ammanford, a preparatory school that catered mainly for nonconformist ministerial candidates. He was a student at the Baptist College and the University College, Bangor, in 1892-5, but his preoccupation with eisteddfod competition in poetry led to a serious neglect of his studies. He spent a year as a student at University College, Cardiff, in 1895-6, before returning to the Gwynfryn as an assistant to the master, Watcyn Wyn.

....Jenkins wrote under the bardic name Gwili, a name which, as Edward Thomas remarked in a pen portrait of his friend, he took from the stream flowing beside his boyhood home, 'whose sound was ever in his ears' (Thomas). The bardic name was later incorporated into the name under which his published work appeared. He won early renown as a poet in the free metres, notably in winning the crown at the national eisteddfod of Wales at Merthyr Tudful in 1901. But apart from eisteddfod compositions he wrote other verse at this time, and indeed all the work included in his collected poems, Caniadau [Songs] (1934), had been completed by 1906. It includes lyric poems and, notably, a poem to the Virgin Mary, a sensitive composition on a subject that might not have been expected to commend itself to a poet of a distinctly protestant adherence in that period. Several of his hymns have been received into the canon of Welsh hymnology. His English verse was collected in his volume Poems (1920). In his literary criticism, while acknowledging the requirements of form and refinement in expression, he laid emphasis on the virtue of subject matter that respected the realities of human experience in its entirety, thereby striking a chord with poets of a younger generation who later found his critical judgement a source of encouragement as they made their breach with older conventions.

....Jenkins was never ordained as the pastor of a church, but he earned respect as a preacher, though his advanced views and the rigour of his argument, no less than the rapidity of his delivery, earned him greater favour among his more percipient hearers. In his published work in scriptural criticism he conveyed his disquiet at the widening gulf between modern biblical scholarship and the outmoded teaching to which the congregations were largely confined. Increasingly concerned, however, at his lack of formal teaching in Christian doctrine he entered Jesus College, Oxford, in 1905 and graduated with a second-class degree in theology in 1908. No new vocational opportunity presented itself and he returned to the Gwynfryn as the school's master for seven years but, fortified by his academic experience, he resumed his scriptural studies with new vigour. In the preface to a volume on the prophets of the Old Testament examined in the setting of the history of Israel, Llin ar lin (1909), he expressed his regret at the churches' continued adherence to 'the doctrine of reserve' under which the benefits of recent scriptural scholarship were deliberately withheld so as to maintain orthodox belief. Commentaries on Isaiah and the epistles to the Thessalonians, written in collaboration, were among the studies which gradually brought contemporary exegesis within the reach of Welsh-language readers.

....Jenkins's liberal theology was matched by a concern that the nonconformist churches' lack of sympathy with those in Welsh society who nurtured socialist aspirations would lead to a damaging alienation. In lectures to branches of the Independent Labour Party in 1909-10, though not formally associated with the movement, he urged the acceptance of an essential consonance of the search for social justice with the teaching of the New Testament. The First World War created new tensions and, as editor of the Welsh Baptist weekly Seren Cymru (Star of Wales), he maintained a consistent critical commentary throughout its duration while still respecting the need to represent the varied viewpoints appropriate to a denominational journal. The issue of recruitment to the forces, exacerbated by the active participation of some ministers of religion in furthering the government's call to arms, and then the issue of conscription, both matters of deep concern, brought forth a sequence of cogently argued editorials. Problems of labour and capitalism in turn drew comments that signalled Jenkins's repudiation of the Welsh denominations' accord with the Liberal Party. In his immediate response to the Easter rising, virtually alone among Welsh commentators, he viewed the events in Dublin not as a regrettable reverse for the war effort but as a tragedy that underlined the government's failure in its responsibility to allow the Irish nation to order its own affairs. His writings on war, labour, and nationality marked a singular contribution to serious discussion during an acute crisis of conscience in Welsh nonconformity.

....With the school at Gwynfryn unable to withstand the coming of war, Jenkins was relieved to be able to accept an invitation to join Professor Thomas Powel as an assistant in the department of Welsh language and literature at University College, Cardiff. By then he was married (the marriage having taken place on 22 August 1910) to Mary Elizabeth (b. 1877/8), daughter of Thomas Lewis, an iron-founder; they had two daughters. At Oxford he had availed himself of the classes of Professor John Rhys in Celtic philology and literature and he took with enthusiasm to his new task of teaching complemented by research in medieval Welsh religious prose, a field in which he was awarded the degree of BLitt in 1918. Powel's retirement and the end of the war brought changes in the department, however, and in 1919 Jenkins accepted a position as librarian of the Salesbury Library, the Welsh collection at the college. Frustrated, but resolved to turn his appointment to good advantage, he applied himself to studies in the field in which he would find fulfilment thereafter. In 1923, now over fifty years of age, he was appointed professor of New Testament Greek at the Baptist College, Bangor, a position that brought him membership of the faculty of theology at the University College. His dedicated application is reflected in two very substantial scholarly works. Arweiniad i'r Testament Newydd (1928), an introduction to the New Testament, provided a comprehensive and enduring work of theological scholarship conceived on a vastly greater scale than anything hitherto attempted in the Welsh language. Hanfod duw a pherson Crist [The Essence of God and the Person of Christ] (1931) provided a detailed exposition of doctrine in the protestant tradition as it was revealed in the adherence of the Welsh congregations and the academies from the teaching of the early eighteenth century to contemporary liberal theology. He was awarded the degree of DLitt by the University of Oxford the next year.

....In 1931 Jenkins's immense contribution to the literary activity of the national eisteddfod was recognized by his election as archdruid of Wales. Assiduous discharge of numerous obligations continued unabated, but the strain took its toll. He died at his home, 38 College Road, Bangor, on 16 May 1936 and was buried on 20 May in the graveyard of the Congregational church, Capel Ty Newydd, Llanedi, Carmarthenshire, on the hillside above the village where he had spent his boyhood and the river that had given him the name by which he was affectionately known. He was survived by his wife. [J. B. Smith]We also find an entry for the English-born Edward Thomas in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, as having satisfied the editors' criterion "that such a person, or at least one of his parents, should have been born within Wales". His writings about Wales and visits here might additionally qualify him for inclusion under the more relaxed rules of the Cymmrodorion above.

THOMAS, (PHILIP) EDWARD (1878-1917), poet; born 3 March 1878, at Lambeth, son of Philip Henry Thomas, Tredegar, clerk in the civil service, and Mary Elizabeth (née Townsend). He was educated at St. Paul's School and Lincoln College, Oxford, 1898-1900, and early showed his love of the countryside, unspoiled people, and literature. He married Helen Berenice Noble, 20 June 1899; there were three children: Mervyn, b. 1900, Bronwen 1904, and Helen Elizabeth Myfanwy 1910. After a couple of years in London they moved to Bearsted, Kent, in 1901, to the Weald (Sevenoaks), in 1903, and to Ashford, near Petersfield, in 1906. His first book, The Woodland Life, was published in 1897, and from then till early 1915 he was the slave of wholesale reviewing and the commissioned book. Oxford, Beautiful Wales, Richard Jeffries, A Literary Pilgrim in England, Feminine Influence on the Poets, Borrow, Swinburne, Marlborough, are a few titles from these years. Overwork and literary frustration increased his melancholy and told on his health. Among his friends were 'Dad' Uzzell, W. H. Davies, Gordon Bottomley, Gwili (John Jenkins, 1872-1936, q.v.), and Edward Garnett. In July 1915 he enlisted in the Artists' Rifles, was transferred to the Artillery later, went to France in Feb. 1917, and was killed at Arras 9 April of that year. Some six months before enlisting he had begun, under the influence of Robert Frost and with the pen name 'Edward Eastaway,' to write the poems on which his fame now rests secure. His Collected Poems appeared in 1920 with a preface by Walter de la Mare. His poems and Helen Thomas's As It Was and World Without End are his enduring memorials.

[Dictionary of National Biography; The Childhood of Edward Thomas (A Fragment of Autobiography), 1938; James Guthrie, To the Memory of Edward Thomas, 1937; J. Moore, Life and Letters of Edward

Thomas, 1939; Gordon Bottomley 'A Note on Edward Thomas' in Welsh Review, iv (1945), 166-78.]1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy for Edward Thomas6. GWILI'S ELEGY FOR EDWARD THOMAS

Gwili was a well known Welsh-language poet of his time but he also published one slim collection of English verse in 1920. English was Gwili's second language and this book possesses little literary merit to today's English-language readership. From this volume we'll reproduce Gwili's elegy written on the death of his friend Edward Thomas. An occasional clumsiness of syntax hints that Gwili may not have been a first-language English writer, but there is genuine emotion to be felt in the elegy, as Gwili describes walks he and his friend took in the area around Ammanford.

Thomas only published six poems in his lifetime the for which he used the pen-name of Edward Eastaway, which explains Gwili's title, as well as the rather weak pun in line 12 and again in the last line. In his elegy Gwili refers to several places in the Ammanford area which are explained by this author in the notes at the end, and are not in the original poem.

EDWARD EASTAWAY

"They are lonely

While we sleep, lonelier

For lack of the traveller,

Who is now a dream only."..(see note 1 below)I miss thee in the dim and silent woods

Where Gwili purled for two who loved her well..(note 2)

Her rippling sweetness through her shrivelled reeds;

And where we played at fishing with our hands,

Or garnered nuts that fell from out their cups,

A voluntary shower; or climbed the bridge,

A gipsy hand to help us gain the road.

The river murmurs still; the hazels pelt

Into the stream their golden affluence.

It is October, and the woods are dim,

And lovely in their loneliness – but thou

Hast travelled west, my Edward Eastaway,

And to these silent woods wilt come no more.I miss thee on th'undesecrated moor

That shelters Llyn Llech Owen, where the cry

Of curlews give us welcome, and the Lake

Of legend led thy dreaming spirit far

To some grey Past, where thou again couldst see

The heedless horseman gallop fiercely home,

And the well drown the moorland with its spate...(note 3)

Again I cross through sedges, and the gorse

Burns like the bush of Horeb unconsumed...(note 4)

The golden lilies in their silver bed

Rustle, and whisper something faint and sad.

Can some maimed wanderer from the fields of France

Have lingered by these waters on his way,

And murmured to the lilies and the reeds

That thou had'st passed along another road

Far to the west, where Llyn Llech Owen woos

No longer, and where lilies are unheard?And most of all I miss thee on the road

To Carreg Cennen, and the castled steep..(note 5)

Thou loved'st in all weathers, and the cave

Of Llygad Llwchwr, and Cwrt Bryn y Beirdd...(note 6)

Thither we wandered in thine Oxford days,

When there were hours of gladness in thy heart

That seemed a hoard thy childhood had conserved,

When song burst out of silence, and the depths

Of thy mysterious spirit were unsealed.Thither we sauntered in the after-years,

When London cares had made thy Celtic blood

Run slow, and thou had'st sought thy mother Wales

Full suddenly – for all too brief a stay.

Lore of the ages, music of old bards

That would have soothed the ear of Golden Grove..(note 7)

And its great exile priest, and brought delight

To Nature's nursling bard of Grongar Hill,..(note 8)

Beguiled the footsore pilgrims many an eve,

Past Llandyfân and Derwydd, past Glyn Hir...(note 9)

It is October, but thou comest not

Again, nor hast returned since that wild night

When we were on this road, late lovers twain,

And thou said'st, in thy firm and silent way,

That all roads led to France, and called thee hence..(note 10)

To seek the chivalry of arms.

.......................................To-night,

The road is lonelier – too lonely far

For one. I turn toward set of sun, since thou

Hast journeyed west, dear Edward Eastaway.[From Poems, published privately in 1920]

Notes 1 These lines are from Edward Thomas's poem 'Roads', written in January 1916. See also note 10 below.

2 The Gwili is the river of that name from which John Jenkins took his bardic name. 3 Llyn Llech Owen (the lake of Owen's stone), is the source of the river Gwendraeth near Gorslas in Carmarthenshire, a lake which comes with its own legend. After Owen Glyndwr watered his horse at a well he forgot to replace the cap-stone before going to sleep. When he awoke the area had flooded so he galloped his horse around the spreading waters to prevent the lake's further overflow. 4 The bush of Horeb (ie Sinai). This is the 'burning bush' of the Old Testament where Moses heard the voice of God speak to him. 5 Carreg Cennen Castle is a medieval fortification at Trap, near Llandeilo, built on a 300 foot high limestone outcrop by Edward I around 1300. It was partially pulled down by Edward IV in 1461 during the Wars of the Roses and has made a splendid ruin for tourists ever since. 6 Llygad Llwchwr (the eye of the Loughor). The source of the river Loughor as it gushes from an underwater lake and cave system near Carreg Cennen Castle. Cwrt Bryn y Beirdd (Bard's Hill Court) is an old farmhouse near Carreg Cennen Castle thought to have some connection with the castle in the middle ages. 7 Golden Grove near Llandeilo, the ancestral seat of the Vaughans and later Earls of Cawdor. The 'exile priest' was the 17th century Bishop Jeremy Taylor, who lived quietly here for a while during the troubled times of the Civil War under the powerful protection of Richard Vaughan, second Earl of Carbery and first Baron Vaughan of Emlyn. 8 Grongar Hill: a wooded hill above the banks of the Towy near Llandeilo, and the title of a fine pastoral poem by local-born poet John Dyer (1700–1758). 9 Llandyfân is a small church near Llandybie. The curative powers of a well alongside the church once drew pilgrims to the spot. Derwydd and Glyn Hir are nearby mansions. Derwydd and its estates, too, were once owned by the Vaughans of Golden Grove, passing to the Stepney Gulstons in time and whose descendant sold the house in 1998. Glyn Hir was the home of the French-descended Dubuisson family from 1770 until 1936. Both mansions are still occupied, though not by the original families. 10 'All roads led to France'. Edward Thomas used these words in 'Roads', 1916. (See note 1 above.)

Now all roads lead to France

And heavy is the tread

Of the living; but the dead

Returning lightly dance.These lines seem to hint that Thomas had a more ambiguous motive for seeking active service in France than the 'chivalry of arms' that Gwili claims for him.

1. Introduction to Edward Thomas

2. Edward Thomas and Ammanford

3. 'Some of his Welsh Friends' by Elis Jenkins

4. Further Material

5. John Jenkins (Gwili)

6. Gwili's Elegy of Edward Thomas