dynasty and the building of AmmanfordCONTENTS

1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources1. INTRODUCTION

THE DYNEVOR COAT OF ARMS. The Crest (at the top) is the black raven of the Rhys family. The Arms (the shield in the centre) has the three ravens for he RHYS side of the ancestry (top left and bottom right quarters). A lion rampart (top right quarter) for the TALBOTs. Three trefoils (bottom left) for the DE CARDONNELs. The supporters are a Griffin (left) and a Talbot (right). The Motto means 'Secret and Bold'

The visitor to Ammanford today will find a small, essentially rural town nestling in the shadow of the Black Mountain. Unlike some of the other towns and villages of the area, it's a fairly recent arrival on the scene with little more than a two centuries of history to call its own. Before that the town was still farmland owned mostly by one family, the Dynevors, who had other parts of Carmarthenshire in their possession as well. Long since built on, the patchwork quilt of tenant farms that once paid rent and obeisance to the local squire has become our modern streets and housing estates, road systems, car parks, supermarkets, shops and factories. The virgin fields given over to arable cultivation, or grazed by livestock, can now only be guessed at from Ordnance Survey and parish tithe maps held in public archives.

The Dynevor estates in 1883 consisted of 7,208 acres in Carmarthenshire, 3,299 acres in Glamorgan, besides 231 acres in Oxfordshire, Wiltshire and Gloucestershire. Total: 10,738 acres, worth £12,562 a year income and the principal residence was Dinefwr Castle in Llandeilo. (Source: The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Vicary Gibbs, London, 1916.) According to Bank of England figures, the pound had a present day purchasing value of £90.64 in 1883 so the above income represents £1,138,685 a year at 2009's values.

The Dynevors though were not the largest landowners in the county; far from it. That distinction must go to the Scottish Earls of Cawdor, whose vast land holdings dwarfed even the substantial acreage of the Dynevors. Their 10,738 acres in 1883 look puny compared to the 33,782 acres the Cawdors owned in Carmarthenshire alone, with another 17,735 acres in Pembrokeshire, and to which can be added 50,119 acres in their home county of Nairn in Scotland. The total of 101,657 acres brought in an annual income of £44,662 in 1883 (that's equivalent to £4,048,394 a year in 2009). Interestingly, the 51,000 acres of prime agricultural land in Wales yielded the Cawdors an annual income of £35,042 (£3,176,387 in 2009) but the 50,000 poorer Scottish acres were worth just £9,620 per annum (£872,006). Their principal residences (note the plural) were Glanfread in Cardiganshire; Stackpole Court, Pembrokeshire; Golden Grove, Llandeilo; and Cawdor Castle, Nairnshire, Scotland. Our source for this information, the 'Complete Peerage', by Vicary Gibbs, also informs us that Earl Cawdor was one of the 28 noblemen who in 1883 owned over 100,000 acres in the UK.

Carmarthenshire historian Francis Jones neatly enumerates the Cawdors' real estate:

The family occupied numerous country houses. At the height of its affluence the parent estate, that of Golden Grove, comprised over 50,000 acres, 27 extensive manors and lordships, and five castles, and when these are added to the lands of the many branches it can be truly said that nearly half of Carmarthenshire owned a Vaughan for landlord. [The Ethos of Golden Grove, Francis Jones, from A Treasury of Historic Carmarthenshire, 2002]

The most famous of the Cawdors, if Shakespeare's three witches are to be believed, was of course Macbeth ("All hail Macbeth! hail to thee, Thane of Cawdor!"). There was a historical Macbeth (1005–1057, and King of Scotland from 1040), but the modern Barony of Cawdor goes back only to 1796, with the Earldom being created in 1827. The modern-day Earls still live in Cawdor Castle, but as this was built in the late 14th century, it has nothing to do with Macbeth, historical or Shakespearean. Their Pembrokeshire residence at Stackpole Court was demolished in 1963 and their equally grand Carmarthenshire seat at Golden Grove was taken over by the county council in 1951 and run as an agricultural college, while the mighty Carreg Cennen Castle and its surrounding farmlands was lost to them in the 1960s. (For more on the Cawdors, including the somewhat devious way it's claimed they acquired the inheritance to the Welsh lands, click HERE.)

After this little digression into the Cawdor's family fortunes, it might now be productive to return to the Dynevors and trace the history of this family who figured so large in Ammanford's past. To do this however we'll have to start the story seven miles north, and a thousand years into the past, at the ancient town of Llandeilo, and where the Dynevor's ancestral seat can still be seen in all its glory.

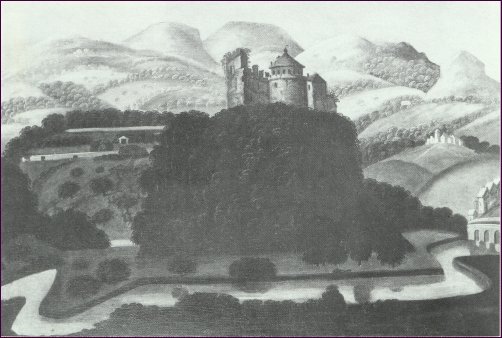

Just a short walk from the centre of Llandeilo are the beautiful parklands of Dinefwr Castle. At the south west corner of the park, on a crag some 300 feet above the river banks, stands ancient Dinefwr Castle with a spectacular view overlooking the river Tywi from its recently restored ramparts.

Aerial view of Dinefwr Castle from the south. Photo by T. A. James (Dyfed Archaeological Trust) from 'Sir Gar – Essays in Carmarthenshire History', edited by Heather James (1991) At the north west corner is the mock-gothic Newton House, medieval in origin, but with 17th, 18th and 19th century additions, and running along the river at the southern side, are the ancient woodlands concealing the slightly spooky, grave-strewn Llandyfeisant Church. Add a deer park and a wetlands area and you have the perfect ingredients for a thoroughly enjoyable morning or afternoon walk. And of course, mention that the beautiful park was laid out by the most sought after landscape gardener of the 18th century, Capability Brown, and your joy will be unconfined (or might be if the rain holds off).

The park's long views look down also on a long history, one that goes far back into the Welsh middle ages (and even further if legend is to be believed). There is an impressive cast of historical characters, too. Start with some fierce Welsh Princes fighting off the advances of the nasty Normans, when they weren't fighting each other that is (they were a quarrelsome lot), before finally being dispossessed of their lands by Edward the First. Then add a knight in shining armour, in this case Henry the Seventh (a Welshman), to restore the lands two centuries later, with another Welshman, Rhys ap Thomas, killing the monstrous King Richard III in the process. Next, enter Henry's villainous son Henry the Eighth, seizing the Rhys lands for the crown yet again, beheading the owner in the process, and all-in-all you have the makings of a rich history indeed, Hollywood material even. The family, by then calling themselves Rice after anglicizing the original name of Rhys, managed to get some, but not all, of their land back eventually thanks to later monarchs Queen Mary and James the First. Finally the family acquired a modern title in 1780 with the creation of the first Baron Dynevor of Dynevor (the current holder of the title is the 9th Baron). The 4th Baron brings the Dynevors back into the glare of history once more with his policing of the Rebecca Riots in 1843. The Dynevors' fortunes increased steadily throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries before declining precipitously in the twentieth century, after death duties struck them a mortal blow from which they never fully recovered. We can however add the obligatory feel-good ending to finish with, for despite the recent Dynevor generations somehow managing to fritter away all that wonderful inheritance, Dinefwr Park is now in public ownership and available for all, not merely one family, to enjoy.

The first recorded occupants of Dinefwr Castle and its lands was the medieval Lord Rhys and his descendants, who ruled the area until 1277 when their lands and castles were siezed by the Anglo-Norman King Edward I. Then, after two hundred years of dispossession by the English crown, the ancestors of the modern Dynevors acquired the estates (and incidentally the name Rhys as well), becoming the dominant political power in Wales. By virtue of being members of that thoroughly outdated, yet curiously persistent species, the aristocracy, the Dynevors have a pretty complete family history going back, they once claimed, to the sixth century. Most of us commoners are lucky if we can go back three generations or so before our genealogy peters out completely, usually with plenty of gaps for unknown great-aunts, intrepid emigrants, and mysterious black sheep. So, we'll trace a little of that Dynevor history from the middle ages to more recent times, by when all the achievements of that splendid, pageant-filled past have evaporated completely, leaving plenty of history but little else besides. Anyone taking a stroll in Dinefwr Park after reading this brief tale will know the history of the most prominent features they encounter but will also know that none of it any longer belongs to the Dynevor family.

1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources2. THE MIDDLE AGES AND DINEFWR CASTLE

The early history of the Rhys/Rice/Dynevor dynasty (ie pre-12th century) is mostly based on conjecture and legend, there being no written records to confirm whatever the imagination has embroidered on time's blank spaces. The legendary part of the ancestry claims a 6th century origin in Uryan Rheged, Lord of Kidwelly, Carunllou, and Iskennen in South Wales. He supposedly married Margaret La Faye, daughter of Gerlois, Duke of Cornwall, and is even credited with building the castle of Carreg Cennen in Carmarthenshire. He had originally been a prince of the North Britons (ie Scots), but was expelled by the Saxons in the 6th century and fled to Wales. And if that's not enough, Uryan Rheged's great-great-grandfather is claimed to have been Coel Codevog, King of the Britons. Coel, who lived in the 3rd century A.D., seems to be the original of the nursery song, 'Old King Cole.' (See The Annotated Mother Goose, William S. and Cecil Baring-Gould, Clarkson N. Potter, 1962.) Well maybe; or then again, maybe not.

Burke's Peerage and Baronetage, that bible for the aristocratically inclined, is more circumspect however, and has this to say about the claims for such an early ancestry:

"The Rices (later Rhyses) have in their time claimed descent from URIEN RHEGED, ruler of an area called Rheged on the English-Scottish borders in the late 6th century. But the known chronology does not fit. Indeed the descent may be from a much later Urien."

The Lord Rhys

Whoever was the Dynevors' ancestor, the name 'Uryan' has been retained as part of their family name to this day (the 9th and current Baron Dynevor is Richard Charles Uryan Rhys). Burke's Peerage goes on to list the earliest known ancestor of the family as being one Einon ap Llywarch, born circa 1150. But early Dinefwr will always be associated with the twelfth century Rhys ap Gruffydd (c. 1132–1197) who was most definitely a historical figure. Rhys was one of the few Welsh Princes to regain territory lost to the Normans. Deheubarth (roughly modern Dyfed) was overrun by the Normans in 1093, remaining in their possession until 1155. Although Rhys and his brothers regained land from the English in Carmarthenshire, Cardiganshire and Glamorgan, they still had to rule under the overlordship of King Henry II (reigned 1154–1189), so that in 1158 Rhys ap Gruffydd submitted to Henry and was forced by him to drop the title of Brenin (King), being known as Yr Arglwydd Rhys (The Lord Rhys), though from surviving documents Rhys styled himself Princeps, ie Prince. While Henry lived, Rhys was a trusted agent and ally, dispelling much nationalist assumption of later centuries that Welsh Princes were unwilling subjects of the Anglo–Normans. (Lord Rhys's great-grandson, Rhys ap Maredudd (died 1291) even fought alongside Edward I against the Welsh, being given Dryslwyn Castle as his reward.) For his part, the Lord Rhys was content to make the most of his relationship with the king, even going to war against fellow Welsh princes with the Crown's support, but he continued to think and act as an independent Welsh prince. By the time of his death in 1197 he had been an active participant in war and politics, and the dominant ruling prince in Wales, for more than forty years.He governed his principality from two centres, the formidable hilltop fortress of Dinefwr high above the river Towy in Llandeilo and Cardigan Castle, rebuilt by him in stone and mortar in 1171, demonstrating that the Welsh could imitate the Normans when occasion demanded. Interestingly, Cardigan was the first recorded Welsh masonry castle; that is, the first stone castle built by the native princes of Wales and it remained the property of the Lord Rhys until his death in 1197. It was at Cardigan Castle that Lord Rhys organised what is recognised as the first ever national Eisteddfod in 1176. (While the winner of the chair for music was a minstrel from Rhys's own household, the poets of Gwynedd won the bardic chair, revealing the cultural and linguistic, if not political, unity of Wales at that time.) It was the Lord Rhys who possibly built the first castle at Carreg Cennen near Llandeilo, though historians are not in complete agreement on this. The impressive stone structure that now stands 300 feet above the river Cennen, watching over five counties, was erected by Edward I around 1300 AD.

According to another of the legends attached to Dinefwr Castle it was built by Rhodri Mawr, King of Wales in the 9th century. By 950 AD, it was thought that Dinefwr was the principal court from which Hywel Dda ("The Good") ruled a large part of Wales including the southwest area known as Deheubarth (Dyfed) along with the kingdoms of Gwynedd and Powys. Hywel's great achievement was to create the country's first uniform legal system, which stood until Henry VIII's Acts of Union between 1536 and 1543 replaced them with English codes of law.

This legend was until recently also the received historical opinion, but has now been rejected by modern historians in favour of the following one expressed in the wonderful 'Castles of Wales' website (better than NASA, honest):

"The Welsh lawbooks of the medieval period, the earliest of which is a text of the 13th century, accorded to Dinefwr a special status as the principal court of the Kingdom of Deheubarth ... The phraseology of the lawyers' statements may give Dinefwr an aura of antiquity, but written sources do not suggest that the castle has any history earlier than the 12th century. The earliest reference to the castle at Dinefwr in historical sources belongs to the period of Rhys ap Gruffydd, the Lord Rhys. One of the greatest Welsh leaders of the 12th century, Rhys ap Gruffydd was able to withstand the power of the Anglo-Norman lords of the March, supported on occasion by the intervention of King Henry II (reigned 1154–89) of England, and recreate the kingdom. He was then able to take advantage of the king's more conciliatory policy in the period after 1171 to maintain stable authority for many years. Deheubarth flourished over a period of relative peace and general harmony, with Welsh culture and religious life, as well as legal and administrative affairs, all benefiting from Rhys's patronage and self-assured governance." (http://www.castlewales.com/home.html)

But not for long. After the death of this great ruler, conflict over the succession arose between his sons, and thereafter the important castle figures repeatedly in the turbulent years of dynastic struggles between the Welsh princes, and the wars between the Welsh and the English in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. In 1213, for instance, Lord Rhys's youngest son, Rhys Gryg (Rhys the hoarse – what a wonderful image that conjures), was besieged in the castle by two of Lord Rhys's grandsons. This wasn't unusual for the times though – Lord Rhys himself had once been attacked and imprisoned by two of his own sons, Maelgwn and Hywel, in 1194. We are also told, that Rhys Gryg was forced to dismantle Dinefwr Castle by Llywelyn the Great, prince of Gwynedd, who became pre-eminent in the area in the early 13th century. But all this chaotic squabbling was to cease, dramatically and suddenly, after the death of Henry III in 1272. His son Edward I now came to the English throne and within five years had destroyed the power of the Welsh princes. In 1276 an English army under Pain de Chaworth was assembled at Carmarthen, and Welsh resistance crumbled. Rhys Wedrod placed Dinefwr in the king's hands in 1277, and from this time the castle remained largely in possession of the English crown.

But that is not to say its history ceased with this calamity; far from it, as Cambria Archaeology informs us:

"Extensive repairs and additions were made to the castle by the English Crown in the 1280s. During latter years of Welsh rule a small settlement – 'Trefscoleygyon' or 'vill of the clerks' – developed outside the castle. By 1294 the town of Dinefwr had 26 burgages, a weekly market and annual fair. The end of the 13th century saw Dinefwr become a twin-town. This consisted of an 'old' town on the hill containing 11 Welsh burgesses [ie modern Llandeilo town], and a 'new' town – soon to be called 'Newton' – containing 35 burgesses of mostly English descent. Newton was located some distance away on the site of the later mansion, Newton House. In 1310 the castle, towns and demesne of Dinefwr were granted to Edmund Hakelut and later to his son. The Hakelut family held their position, apart from a short break, until 1360. Repairs to the castle were carried out under the Hakeluts. A survey of 1360 indicates that Newton was a successful settlement with 46 burgesses. A charter was granted to the towns in 1363, but this seems to have marked a high point in the towns' fortunes.

......The castle and towns were besieged in 1403 during the Glyndwr rebellion. Following the revolt the towns and castle were granted to Hugh Standish. The Standish family had little interest in south Wales, and both the castle and towns went into decline. In 1433 responsibility for the towns and castle was separated, and the towns and demesne were granted to John Perrot. His cousin married Gruffydd ap Nicholas, and so began the long association with the Gruffydd family. By the time that Gruffydd ap Nicholas's grandson, Rhys ap Gruffydd, was attainted of treason in 1531 his family had built a mansion among the ruins of the former town of Newton, although 'Newton' was still marked on Saxton's map of Carmarthenshire of 1578. The age of the towns and castle had come to an end." [Note: a 'burgage' was a tenure of land in a town on a yearly rent.](from the Cambria Archaeology website http://www.acadat.com/HLC/HLCTowy/area/area195.htm)

Dinefwr Castle was finally abandoned in the 15th century in favour of the more convenient site of the first Newton House lower down. (It was in this century that castles ceased to have significant military value – the earlier invention of gunpowder and cannons had seen to that.) As if to emphasize this, a purely decorative summer house was added about 1660 to the top of the circular medieval keep, the remains of which still survive. The age of the style guru had finally arrived.

Dinefwr Castle from the south in 1660 by an unknown artist. The decorative summer house can be seen on top of the circular keep, The building which pre-dated the modern Newton House is in the distance, middle right. Llandeilo Bridge (in reality a mile upstream) can be seen bottom right. (Nat. Lib. of Wales, Welsh Folk Museum) 1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources3. THE ACQUISITION OF THE LANDS

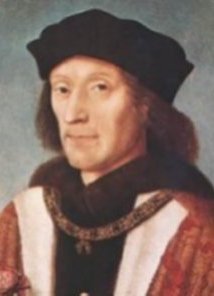

"The Lord gave and the Lord hath taken away." (Job, chapter 1, verse 21). The Lord who gave in this case being Henry VII (left), who rewarded the Rhys family with lands in 1485, only for his son Henry VIII (right) to seize them back again in 1531, beheading the owner in the process. (See below for the full story.) Gruffydd ap Nicholas (1400–1461)

When Edward I dispossessed the medieval Rhys family of their kingdom in 1277, their lands remained in the possession of the various Kings of England for almost 200 years. But eventually another Welshman, Henry Tudor (who was born and raised in Pembroke Castle), became Henry the Seventh of England (born 1457, reigned 1485–1509) and he returned the lands into Welsh hands. During the intervening two centuries one local Welsh family, that of Gruffydd ap Nicholas and his sons, had become pre-eminent in the Towy valley area and in 1440 he started to lease Dinefwr Castle and its lands from the crown, while accumulating other estates and properties at the same time. Gruffydd and his numerous sons became the most powerful native Welsh family during the mid-15th century, ruling effectively – and occasionally violently – with little control from a King (Henry VI) who, in between bouts of madness, was otherwise occupied with losing his possessions in France and his crown in England. In 1461 the Yorkist Edward, Duke of March became Edward IV of England when he seized the throne from the Lancastrian Henry VI. During this period of dynastic turmoil Gruffydd himself was killed at the Battle of Mortimer's Cross in 1461, and for their support of the defeated Lancastrians his sons forfeited the family's extensive lands in the Tywi valley. (But not before two of them, Thomas and Owain, had held Carreg Cennen Castle against a Yorkist onslaught of 200 men in 1462, only surrendering after a siege. To ensure no such resistance occurred again Carreg Cennen's fortifications were destroyed afterwards. It has never been occupied since.)Sir Rhys ap Thomas (1449–1525)

The family's fortunes may have looked bleak during the Yorkist occupation of the throne from 1461 but one of Gruffydd ap Nicholas's grandsons, Rhys ap Thomas, was waiting patiently in the wings and would soon become the most prominent member of this extraordinary clan, directly ancestral to the modern Dynevors (see Burke's Peerage.) When Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond (who was distantly related to Rhys ap Thomas), seized the English throne from Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, Rhys ap Thomas's fortunes were to change dramatically. Richard's death on a muddy Leicestershire field marked the end of the thirty year dynastic struggle later historians have called the 'Wars of the Roses' and Henry, now King, gave Dinefwr Castle and its lands to Rhys ap Thomas. Rhys had raised an army in support of Henry in 1485 so the restoration of the lands was his reward, as was the knighthood granted by Henry just three days after Bosworth.

Richard III, who was killed after a two hour battle at Bosworth, near Leicester, on 22nd August 1485, reputedly by Rhys ap Thomas. This battle ended the Wars of the Roses (1455–1485) and with it the Plantaganet dynasty which had ruled England (and eventually Wales) from 1154–1485. The victor at Bosworth, Henry Tudor (Henry VII), inaugurated the Tudor dynasty (1485–1603). A biography of Rhys ap Thomas written about 1625 claimed it was he who actually struck down and killed Richard, though contemporary history is silent on who actually struck the fatal blow. "King Richard, as a just guerdon [reward] for all his facinorouse [vile] actions and horrible murders, being slain in the field. Our Welch tradition says that Rhys ap Thomas slew Richard, manfully fighting with him hand to hand." ('Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', Ralph A. Griffiths, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1993, page 229–230.)

(Shakespeare in his play Richard III has Henry Tudor himself kill Richard, but historical accuracy was often sacrificed for dramatic effect by Shakespeare.) Walk in the main courtyard of Dinefwr Castle today and you could conceivably claim to be standing literally in the footsteps of the man who dispatched an English King to the next world. And as you look out from the castle you could just as easily imagine Rhys's army passing within view of the ramparts on its way to join Henry in August 1485.

The armies of Henry and Rhys formed a pincer movement that started from south west Wales. Rhys and his men (which included 500 cavalry) began their historic campaign at Carmarthen, marching eastwards along the Tywi Valley through Llandeilo and Llandovery, then turning north at Brecon to meet up with Henry's army near Shrewsbury on 13th August 1485. Henry and his forces, which started off as a mixed Scots, French and English army, had landed from France at Milford Haven on 7th August 1485. From here they marched up the west coast of Wales, gathering Welsh support as they went, before turning east at Machynllech and joining the rest of their supporters, by now augmented by Monmouthshire and north Walean contingents (the Tudor line – also spelled Tudur and Tewdur – originated in Anglesey.) These combined forces, crucially strengthened by various English magnates and their troops (Henry was after all making a bid to depose the King of England), finally engaged with Richard at Bosworth Field on 22nd August 1485.

Rhys's loyalty to Henry once he became King was not something that could have been predicted before that date however: he had initially made a sworn oath of fidelity to Richard III (and in February 1484 had been granted an annuity for life by him) but he must have weighed up each's chances of victory and decided that Henry looked the better bet. He was proved right, and prospered accordingly when Henry's forces romped home on Bosworth Field that fateful August day. The oath he was supposed to have made to Richard was, according to a legend which has found its way down the ages: "Whoever ill-affected to the state, shall dare to land in those parts of Wales where I have any employment under your majesty, must resolve with himself to make his entrance and irruption over my belly." The story is told that after Henry Tudor's return to Britain (at Dale, Pembrokeshire, in 1485) Rhys eased his conscience by hiding under Mullock Bridge, Dale, as Henry marched over, thus absolving himself of his oath to Richard. Of such stuff are legends made and the story, though not necessarily true, seems rather too good not to repeat.

Opportunism, not loyalty, seemed to be the motive that spurred others, not just Rhys, to join Henry. His step-father Thomas, Lord Stanley and his brother Sir William Stanley had raised 8,000 troops between them in the name of Richard, not Henry. But neither Henry nor Richard knew for certain on whose side the Stanley brothers intended to intervene and when William Stanley eventually committed his 3,000 troops for Henry, it was after the main battle had started. Thomas Stanley and his 5,000 men remained aloof throughout the fray, though the knowledge that Richard held his son hostage would easily explain such reticence. (See John Davies, 'A History of Wales', page 218.)

For his support, Henry showered titles and rewards on Rhys ap Thomas for the rest of his life, who was made Governor of all Wales amongst many other lucrative appointments. A biography of Rhys written in the early 17th century by a descendent of his, one Henry Rice, lists Rhys's titles as: "Rice ap Thomas, Knight, Constable and Lieutenant of Breconshire; Chamberlain of Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire; Seneschall and Chancellor of Haverfordwest, Rouse and Builth; Justiciar of South Wales, and Governor of all Wales; Knight Bannerett, and Knight of the Most Honourable Order of the Garter; a Privy Councellor to Henry VII, and a favorite to Henry VIII." ['Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', Ralph A. Griffiths, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1993, page 148.]

Rhys came to Henry's aid many times during his reign, notably in 1487 and 1497 when he commanded armies that put down rebellions against the still-new Tudor rule. Rhys even lived long enough to render service to Henry's son, Henry VIII, who at the age of twenty-two invaded France in 1513 and defeated the French at the 'Battle of the Spurs' in Artois. Rhys, aged about 65, was in attendance on that day twenty-eight years after the battle that inaugurated the age of the Tudors. Rhys ap Thomas (born 1449) died in 1525 and his tomb can still be seen today in St Peter's Church, Carmarthen, after being moved from Carmarthen Priory where he was originally buried. Also buried at this priory were the remains of Henry VII's father, Edmund Tudor, who died in November 1456, just two months before Henry's own birth in January 1457. (Edmund's tomb was removed to St David's Cathedral on the dissolution and destruction of Carmarthen Priory, ironically by his own grandson, Henry VIII.) Edmund Tudor had been created Earl of Richmond by Henry VI and the title therefore passed to his son Henry Tudor at birth. Henry had been brought up by his father's brother, Jasper Tudor, whom Henry VI had created Earl of Pembroke. Henry VI was in fact the half-brother of Jasper and Edmund Tudor, just one of many examples of how closely related were the leading actors in the Wars of the Roses. It didn't stop them slaughtering each other with almost comical frequency, however. About 60 leading families effectively ran England and Wales at this period, all inter-related by blood or marriage, and it's been estimated that one in ten of their adult males were killed during the Wars of the Roses. (See Lady Catherine Howard below for more examples of such close inter-relatedness.)

Rhys ap Gruffydd (1508–1531)

The next king after Henry VII, the much more famous (or infamous) Henry VIII (born 1491, reigned 1509–1547) reverted to type and seized the lands back from Rhys ap Thomas's grandson, Rhys ap Gruffydd, who was accused of plotting with the King of Scots to overthrow Henry and make himself ruler of Wales. The charges were preposterous and fabricated but it was Rhys's misfortune to be guilty of a crime greater even than treason in Henry's eyes, that of owning extensive estates when Henry was in permanent need of money. Rhys's fate was sealed and he was executed in 1531, having no chance of justice at the hands of a man who would soon behead two of his own wives (Anne Boleyn in 1536 and Catherine Howard in 1542).It has to be said that at the time of his trial for treason, Rhys ap Gruffydd had already been arrested and imprisoned for various acts of riot against the King's new representative in Wales, Lord Ferrers, which had resulted in several of Ferrer's associates being killed. When Rhys ap Thomas had died in 1525 aged 76, the King awarded most of his titles and powers, not to Rhys's heir, his 17 year old grandson Rhys ap Gruffydd (whose father had died in 1521), but to the Englishman Walter Devereux, Lord Ferrers – and had awarded them for life, at that. For the rest of Gruffydd's short life he harboured a deep grudge against Ferrers and the two were at daggers drawn, in one case quite literally when Rhys burst into Ferrers room in Carmarthen Castle in June 1529 with 40 armed men and threatened Ferrers with a knife. Rhys was arrested and imprisoned in Carmarthen Castle and Rhys's wife, Lady Catherine Howard, then went even further, raising several hundred supporters and storming Carmarthen Castle, demanding Rhys's release and threatening to burn down the castle gates! Some months later she even laid siege to Lord Ferrers and killed several of his men. Stand by your man doesn't even begin to describe it. There were other skirmishes and riotous assemblies during which lives were lost (and Rhys even engaged in piracy from Tenby) so that by October 1431 Rhys was in prison in London, and it was during this period that the additional charges of treason were laid against him.

Lady Catherine Howard was the aunt of two of Henry VIII's future wives, Anne Boleyn and another Catherine Howard, both of whom were beheaded by Henry. As Oscar Wilde might have said: "To lose one niece, Lady Catherine, might be regarded as a misfortune; to lose both looks like carelessness." Almost immediately after Rhys ap Gruffydd was executed in 1531 Lady Catherine made a wealthy remarriage to the Earl of Bridgewater but her newly found respectability didn't seem to curb her enthusiasm for plunging headfirst into trouble. In 1542 she was convicted of treason herself for covering up the adultery of her niece and namesake Catherine Howard, the 5th wife of Henry VIII, who had just been beheaded for this offence. Lady Catherine's lands were briefly confiscated on her conviction but were returned to her when she was pardoned in 1543. She died in 1553. (The full story can be found in Chapter 4, 'Crisis and Catastrophe', of Ralph A Griffiths excellent book 'Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1993.)

Despite Rhys ap Gruffydd's high-handed and unruly behaviour (to put it mildly) it does appear that the charges he was actually executed for were trumped up (the others certainly weren't). As Ralph A Griffiths in 'Rhys ap Thomas and his Family' sums up:

"Rhys's execution ... was an act of judicial murder based on charges devised to suit the prevailing political and dynastic situation ... and of developments that in retrospect made him one of the earliest martyrs of the English Reformation." ('Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', Ralph A Griffiths, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 1993, pages 110 and 111)

A 19th century historian neatly sums up all these events thus:

"The Dynevor estates were given by Henry VII to Sir Rhys Ab Thomas, and descended with his other possessions to his grandson Rhys AB Gruffydd, from whom, through an act of the most cruel injustice, they again reverted to the crown, in the reign of Henry VIII. Rhys's ancestors had been in the habit of occasionally adding AB Urien, or Fitz Urien, to their names, in conformity to the general Welsh practice, in order to show their descent ['AB' and 'Fitz' both mean 'son of'']. This designation, after being disused for some time, was again adopted, probably in a vain frolic, by young Rhys. The circumstance being reported to the king, and being associated with the immense possessions and unbounded popularity of the family, was construed [by Henry the Eighth] into a design to assert the independence of the principality, and to dissever it from the English government. It was also supposed, without the shadow of proof, that this was part of a concerted plan to depose King Henry, and bring to the English throne James V of Scotland. To increase the absurdity of the whole business, the plot was said to be founded on an old prophecy, that James of Scotland with the bloody hand, and the Raven, which was Rhys's crest, should conquer England. On such frivolous grounds was this young chieftain, himself one of the first commoners in the realm, and connected by marriage with the family of Howard, arraigned for high treason, found guilty, and beheaded.

......On the accession of Queen Mary, his son, Gruffydd AB Rhys, had his blood restored, and received back part of the estates; and Charles I relinquished to Sir Henry Rice all that were at that time of them in the hands of the crown. The estates thus restored to the family were valued at about three hundred pounds a year; these constitute their present Welsh territories, and are all that remain to them of the princely possessions of their ancestors.

......The house of Dynevor has always held considerable influence in the county [ie Carmarthenshire], and has in several instances furnished its parliamentary representatives. George Rice, who died in 1779, married in 1756 Lady Cecil Talbot, only child of William, Earl Talbot. This nobleman was afterwards created Baron Dynevor, with remainder to his daughter, who, on his death in 1782, became Baroness Dynevor. On the death of her mother in 1787, she took the name and arms of De Cardonel, which are still borne by the family. Her ladyship died on the 14th of March 1793, and was succeeded by her eldest son George Talbot Rice, the present Baron Dynevor [in 1815]."

(Thomas Rees, The Beauties of England and Wales, 1815. Reprinted in A Carmarthenshire Anthology, edited by Lyn Hughes, Christopher Davies, 1985, pages 107–108)Restoration, Rehabilitation ... and murder: Gruffydd Rice (1526–1592)

The next generations of the Rice family (as they now styled themselves) concentrated all their efforts on recovering the extensive lands that had been forfeit by Rhys ap Gruffydd's 'treason'. The possessions were so widespread that the King had to send teams of officers to Wales to track down land and properties that were scattered all over the three west Wales counties plus Glamorgan and Breconshire. Most of the confiscated lands were then sold or leased off, often to the Rice's own relatives, with the money going straight into the coffers of the crown. (The family's favoured lands in the Llandeilo and Dryslwyn area were granted to the son of Lord Ferrers, the arch-enemy of Gryffudd's father, which must have rankled.) By the time of Henry VIII's death in 1547 three quarters of all the Rice's Carmarthenshire properties had been disposed of and all the Pembrokeshire ones.Henry VIII's daughter, Queen Mary (reigned 1553–1558), restored some of the lands to the next member of the Rhys family, Gruffyd Rice (though she sold or leased much more to other people) and James I (reigned 1603–1625 ) returned some more. Gruffydd Rice (1526–1592), the son of the beheaded Rhys ap Gruffydd, is listed in Burke's Peerage as the first member of the family to start using the surname Rice, the anglicised version of Rhys. He appears to have worked hard, first in an attempt to clear his father's name of treason – an important matter to the status-conscious gentry – and then to recover some of the lands of his inheritance. No sooner had this been achieved however, than he rather unwisely embarked on the family hobby – murder – and thus undid all his good work. On a visit in 1557 to County Durham (where he had been brought up as a child in the care of the Bishop of Durham after his father's execution), he conspired with a local woman to murder her husband; the motive has not come down to us but this may be one of those occasions when guesswork might be as accurate as any historical record.

Ralph A Griffiths describes the affair: "Gruffydd and his servant fled to Wales and on the 10th October Gruffydd's lands and properties were seized ... Gruffydd was attainted and forfeited the lands and properties which he had been slowly re-assembling over the past decade. It was a major setback in the campaign of rehabilitation and recovery." (Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', page 120.)

Gruffydd was fortunate to be pardoned in 1559 by the newly crowned Queen Elizabeth (reigned 1558–1603) but not surprisingly had little luck with the recovery of his lands. Elizabeth did however return some of his mother's lands in south Pembrokeshire and the Llandeilo and Iscennen (modern Llandybie) estates to Gruffydd in 1560, which amounted to about 1,000 acres in total, little more than today's Dinefwr Park. But in 1623 the next member of the Rice dynasty, Gruffydd's son Walter Rice (1562–1636) was granted the Tywi Valley estates in full by James I – but only if he conceded his mother's Pembrokeshire lands.

Sir Walter Rice (1562–1636)

The past rarely comes down to us without an irony or two to brighten up our day: in 1629 the new King Charles I (reigned 1625–1649) granted a petition to Walter Rice for the return of all the lands still in the possession of the Crown – but on the same day (13th January 1629) that the Crown disposed of the last of the Rice's lands, making it now somewhat pointless in seeking their return. Kings do have a sense of humour, it would seem. The Rices did increase their land holdings in later centuries, but by inheritances and judicious marriages such as that into the wealthy Hobby family of Neath Abbey about 1700 and the Talbot family in 1756. Sir Walter Rice, who by all accounts was quite a spendthrift and therefore in constant need of money, had been most persistent, if unsuccessful, in his attempts to persuade, first King James I and then Charles I, to return his inheritance, writing petition after petition in pursuit of his claim. According to Ralph A Griffiths:"He even enlisted an acquaintance, Thomas Jones (died 1609) – the celebrated Twm Sion Cati – who compiled pedigrees for a number of self-regarding Welsh families ... His pedigree for Walter Rice was completed on 22nd March 1605. Its purpose was to display Walter's descent from kings and English noblemen: "descended from seven kings, five dukes, fifteen earls and twelve barons and all but nine descents [ie generations] between the first and the farthest of them." (Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', page 127.)

Twm Sion Cati is famous in Welsh legend as a sixteenth century Robin Hood figure who hid in a cave near Rhandirmwyn in the upper Tywi Valley, robbing from the rich to give to the poor, and it would appear he was keeping his hand in even after he became respectable. Compilers of family pedigrees don't appear to have changed much in 400 years – they will still prove your descent from the king or queen of your choice, provided you pay enough for it of course. It was Sir Walter's son, Sir Henry Rice (1590–1651), who wrote the biography of Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his family, sometime in the 1620s, in an attempt to rehabilitate the family name, though it was not published until 1796.

The End of an Era

When the executioner's axe fell on the neck of Rhys ap Gruffydd on the morning of 4th December 1531, five generations of rule – and often misrule – by this extraordinary Llandeilo family effectively came to an end. The crown then seized all their lands and possessions, leaving later generations of the family with little of their wealth and none of their power ever again. In the Middle Ages the leading families of Wales were virtually a law unto themselves (and sometimes quite literally so). They ruled more or less as they pleased, free from any constraints from English kings and their leading families, who were often occupied by military campaigns in France during the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) and later by dynastic struggles at home. If the long arm of the English law ever reached into Wales, the first generations of the Rhys dynasty (whose circle of family and friends made up the magistracy), usually had no problem evading its clutch. The young and headstrong Rhys ap Gruffydd clearly hadn't realized that times had seriously changed by 1531, when the power of the English state had not only been strengthened but also centralised in the hands of the monarch and his powerful leading ministers.But not everyone mourned the passing of this family who, for more than a century, were the law in the areas under their control. Those who were on the receiving end of their rise to power rarely had a chance to voice their thoughts. That was left to one Ellis Gruffudd, a Flintshire historian who knew Rhys ap Gruffydd, and had been present when Rhys and Lord Ferrers were hauled before a London court for their various affrays in Carmarthen. Ellis Gruffudd has left us a fitting epitaph for the whole dynasty, not just Rhys ap Gruffydd, for whose execution it was gloatingly written:

"And indeed many men regarded his death as Divine retribution for the falsehoods of his ancestors, his grandfather, and great-grandfather, and for their oppressions and wrongs. They had many a deep curse from the poor people who were their neighbours, for depriving them of their homes, lands and riches. For I heard the conversations of folk from that part of the country that no common people owned land within twenty miles from the dwelling of Sir Rhys ap Thomas, that if he desired such lands, he would appropriate them without payment or thanks, and the disinherited doubtless cursed him, his children and his grandchildren, which curses in the opinion of many men fell on the family, according to the old proverb which says – the children of Lies are uprooted, and after oppression comes a long death to the oppressors." (Sir Rhys ap Thomas and his Family', pages 72–73.)

1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources4. THE DYNEVOR TITLE

It is still unclear why Sir Rhys ap Thomas was never given a title after his support of Henry Tudor at Bosworth Field in 1485; he did, after all, become the most powerful man in Wales under both Henry VII and Henry VIII, but perhaps his Welsh family connections weren't prestigious enough to impress the status-conscious English aristocracy. The Rhys (or Rice) family may have had their lands at least partially restored in the Tudor and Stuart reigns but the much-sought prestige of a title eluded them for quite some time afterwards, and even then was acquired indirectly by marriage. The modern Dynevor peerage dates back only to 1780 when William Talbot, Baron Talbot of Hensol, was created the 1st Baron Dynevor (anglicized spellings were more in keeping with the fashion of the day so Dinefwr had to go). The title came into the Rice family by the marriage of George Rice to William Talbot's only child and daughter, Cecil. (Walter Fitz Uryan Rice became the 7th Baron Dynevor on the death of his father in 1911 but by 1916 being Welsh had come back sufficiently into fashion for him to change the name Rice by royal assent back to Rhys! But not before a street in Betws built on Dynevor land had been named Rice Street after him in 1906.)

The First Baron Dynevor of Dynevor

According to The Complete Peerage (Vicary Gibbs ed.), the first Baron Dynevor was William Talbot, Baron Talbot of Hensol, co Glamorgan, who succeeded his father in that dignity as 2nd Baron [Talbot] on 14 Feb 1737.

......He was created Earl Talbot with the usual remainder on 29 March 1761. Having no male issue, he was created Baron Dynevor of Dynevor, co. Carmarthen for life on 17 October 1780, with a special remainder in favour of his only child, Cecil Rice, widow and the heirs male of her body. [Cecil Rice was his daughter.]

......William Talbot was born 16 May 1710 at Worcester, educated at Eton 1725–1728 and matriculated at Oxford (Exeter college) on 23 January 1727/28. He was created DCL (Doctor of Civil Law) on 12 June 1736. He was MP for co. Glamorgan (1734–1737), Trustee (21 March 1733–4) and Member of the Common Council for Georgia, 17 March 1736/7–1738.

......He was Colonel of the Glamorganshire Militia, 1760. Having been a supporter of Frederick, Prince of Wales, he was (by his son, George III, soon after his succession) created Earl Talbot (19 March 1761.) He was a Privy Councillor (25 March 1761) and Lord Steward of the Household, 1761 till his death. He was present at the marriage of George III and acted as Lord High Steward of England at the coronation and carried St Edward's Crown.

......He married, 21 Feb 1733/4, at St George, Hanover Square, Mary, daughter and heir of the Right Hon. Adam De Cardonnel, of Bedhampton Park, co. Southampton, Secretary at War, by his 2nd wife Elizabeth, sometime wife of William Frankland, daughter and heir of Rene Baudouin of London, merchant.

......He died 27 April 1782 at Lincolns Inn Fields and was buried at Sutton."

......[Source: E-mail from the House of Lords website: http://www.parliament.uk]The Talbot Peerage is somewhat unusual in that the 2nd Baron Talbot was also an Earl who could add 1st Baron Dynevor to his roll call of titles, while the 2nd Baron Dynevor muddies the waters even further by being a woman (life gets thoroughly confusing when you're a peer of the realm, doesn't it?).

William, 2nd Baron Talbot was created the Earl Talbot in 1761. On 17 October 1780, he was granted the additional title of "Baron Dinevor, of Dinevor, county Carmarthen" with a special remainder to his only daughter, Cecil.

......Upon the Earl's death on 27 April 1782, the Earldom of Talbot became extinct, the Barony of Talbot passed to his nephew (which is now part of the Earldom of Shrewsbury) and the Barony of Dinevor (Dynevor) passed to his only daughter who later assumed the surname de Cardonnel.

......Upon the death of the 2nd Baron Dynevor on 14 March 1793, the title passed to her elder son George Talbot, who become the 3rd Baron Dynevor, resuming his paternal surname of Rice in 1827 (he died 9 April 1852).

[Source: E-mail from the website http://www.HereditaryTitles.com]The current holder of the titles of Earl Talbot and Baron Talbot is a gentleman bearing the full, resplendent name of (are you ready for this?): Charles Henry John Benedict Crofton Chetwynd Chetwynd-Talbot, Premier Earl of both England and Ireland – 22nd Earl of Shrewsbury and Waterford, 7th Earl Talbot, Viscount Ingestre and Baron Talbot. (Source: Burke's Peerage.)

The Dynevors seem to have been prouder of the length of their ancestry than their achievements. In a book 'A Peerage for the People' by William Carpenter, first published in 1835, and again in 1841 with updates, George Talbot Rice, the 3rd Lord Dynevor, is described thus: "Baron Dynevor – This Peer is descended from Adam on the mother's side, and from the Lord knows who on his father's!" William Carpenter might even be justified in this sneering comment: as we've seen, the Dynevors once claimed their descent from 'Old King Cole' as far back as the 3rd century, no less, and "seven kings, five dukes, fifteen earls and twelve barons" were once branches on their family tree, or so they claimed.

If William Carpenter was contemptuous of the Dynevors' pretensions, the 3rd Lord was fortunate to get off so lightly from an author who described the aristocracy of his day in these stinging terms:

"The history of the Peerage is a history of intrigue, profligacy, corruption, jobbing, and peculation. Repulsive as the Spirit of Aristocracy has ever been, it is not to be doubted that it has, in many features, largely degenerated over the last two hundred years ... its high chivalry has degenerated into pure chicanery; its lofty courage has degenerated into low cunning."

The current Lord Dynevor is Hugo Griffith Uryan Rhys, born 19 Nov 1966. (Source 'Who's Who'.) And for those who are interested in such matters here are the dates for all the ten Barons (each Lord succeeded to the title on the death of the previous one):

Summary of Lineage:

The story of their line is one of ruthless founding fathers, replaced later by status-conscious gentry seeking recognition in London, and tending to dissociate themselves from direct involvement in Welsh regional affairs. The home seat of the family was at Dinefwr, Llandeilo, which the Rhys line held almost wholly from the 15th century. In Henry VI's reign the head of the Rhys family, Griffith ap Nicholas, was a man of great wealth, and consequently power and influence, related by marriage to the principal families of North and South Wales, and he caused a large Estate to be built up at Dinefwr. Thomas ap Griffith, the Courteous, succeeded his father followed by his son Sir Rhys ap Thomas, whose career shaped the making of English history, since it was he who was instrumental in Henry VII's victory at Bosworth field in 1485, and where tradition claims he killed Richard III. Despite some reversals in fortune the Rhys family flourished at Dinefwr, bearing a dominating role in Welsh influential circles. Many improvements were made to the Estate, and in 1775 Capability Brown was invited to lay out the magnificent parkland. The Neath Abbey Estate connection had come about through the marriage of Griffith Rice, an ancestor of the Barons Dynevor, to Katherine, daughter of Philip Hobby of Neath Abbey, around 1700.

1st Baron William Talbot, Earl Talbot and 2nd Baron Talbot (born 16 May 1710 – died 27 April 1782) 2nd Baroness Cecil De Cardonnel, Baroness Dynevor (born July 1735 – died 14th May 1793) 3rd Baron George Talbot Rice (born 8th Oct 1765 – died 9th April 1852) 4th Baron George Rice-Trevor (born 5th Aug 1795 – died 7th Oct 1869). He died without male issue and his cousin, the Reverend Francis William Rice succeeded to the title. Most of the family wealth passed to his four daughters, leaving only the estates and the title to the 5th Baron. Armed with hindsight, we might discern in this the beginning of the slow decline in the family's fortunes. 5th Baron Francis William Rice (born 10th May 1804 – died 3rd Aug 1878) 6th Baron Arthur De Cardonnel Rice (born 24th Jan 1836 – died 8th June 1911 7th Baron Walter FitzUryan Rice (born 17th Aug 1873 – died 1956) 8th Baron Charles Arthur Uryan Rhys Rice (born 21st Sept 1899 – died 1962). An M.P. for Romford and Deputy Chairman of the Sun Insurance Company. The Neath Abbey estates were sold by him at auction in September 1946. When he died at the age of 62, death duties previously incurred by the 7th Baron had not been paid, placing an intolerable financial burden on the next in line of descent namely Richard Charles Uryan Rhys 9th Baron Richard Charles Uryan Rhys, (born 19 June 1935 – died 12th Nov 2008). Richard Rhys inherited after his father's death the remaining holding of the Llandeilo Estate, comprising 23 farms, and 2,000 acres, a ruined castle, a deer park with a herd of rare long horned white cattle, and a death duties debt outstanding in six figures. (Farms were sold off and some attempt made to save the Hall as an Arts Centre, but ultimately it was sold to a private buyer in 1974.) The National Trust acquired the deer park and the outer park at Dinefwr in 1987. Newton House was purchased by the Trust in 1990 having been through several hands since first sold by Lord Dynevor in 1974. The East Drive was acquired in 1992. The generosity of the Heritage Lottery Fund facilitated the purchase of Home Farm and Penparc in 2002. The 9th Baron resided in Chiswick, London, and the Llandeilo area, and his chief interest was in the Raven Book Publishing Company, of which he was a Director. 10th Baron Hugo Griffith Uryan Rhys, born 19 Nov 1966. A detailed lineage of the nine Barons can be found by clicking HERE.1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources5. DINEFWR PARK

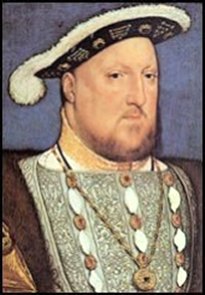

As well as Dinefwr Castle detailed above, the modern Dinefwr Park consists of two other major features: Newton House and Castle Woods (with Llandyfeisant Church).

Map showing the main features of Dinefwr Park. From 'Sir Gar – Essays in Carmarthenshire History', edited by Heather James (1991) Newton House

The National Trust, current owners and custodians of Newton House, describe the house and Dinefwr Park:"An 18th-century landscape park, enclosing a medieval deer park, Dinefwr is home to more than one hundred fallow deer and a small herd of Dinefwr White Park Cattle. A number of scenic walks are available including access to Dinefwr Castle, with fine views across the Towy Valley. There is also a wooded boardwalk, particularly suitable for families and wheelchair users. Newton House, built in 1660, but now with a Victorian façade and a fountain garden, is at the heart of the site. It has two showrooms open to the public, a tea-room which looks out onto the deer park and an exhibition on the history of Dinefwr in the basement." (The National Trust website http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk.)

There had been a manor house on the ancestral estate at Dinefwr Park since the 15th century but It was in 1775, at the time of Sir George Rice MP and father of the 3rd Baron, that the grounds were remodelled by Capability Brown in the fashion of the time – a carefully controlled 'wilderness' of sweeping parkland, punctuated by groups of towering trees, when the medieval castle, house and gardens were amalgamated into one large landscape. Although the present Newton House dates back to 1660 and Sir Edward Rice – the great-great-great-great-great grandfather of the present Lord Dynevor – the house has substantial 18th-century and Victorian Gothic additions.

Newton House has had something of an unhappy recent history. It was sold by the present Lord Dynevor in 1974 and suffered badly thereafter, falling into near ruinous disrepair. It was occupied by squatters for some years and was stripped of many of its original features. (No more than two people at a time are allowed on the top floor because the structure has been weakened by the removal of beams and joists for firewood!)

Mercifully, both the medieval castle and Newton House have recently been restored by Cadw and the National Trust respectively, who now run the park, its buildings and a tea shop. Dinefwr Park is also open to the public. Check the National Trust website for opening times, admission prices etc on: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk. Since being restored to something resembling its former glory, Newton House has become an important feature of Llandeilo's cultural life, providing a superb setting for concerts and exhibitions as well as being licensed for civil weddings. The National Trust acquired the deer park and the outer park at Dinefwr in 1987. Newton House was purchased by the Trust in 1990 having been through several hands since first sold by Lord Dynevor in 1974. The East Drive was acquired in 1992. The generosity of the Heritage Lottery Fund facilitated the purchase of Home Farm and Penparc in 2002 and the site of a major Roman fort has since been discovered on the land, so an exciting prospect lies ahead when the site, hopefully, is excavated in the near future. Dinefwr Park is now 286 hectares in extent (707 acres), somewhat less than the 10,738 acres the family owned in 1883, but impressive nonetheless.

The organisation responsible for the Welsh architectural heritage is CADW (Cadw means 'to keep' in Welsh) who describe Newton House thus:

"Newton Mansion continued to be occupied by the Rice (Rhys) family and was partly rebuilt between 1595 and 1603, again in c.1660, and in c. 1757–1779, and then in its present form in 1856–1858 by Richard Kyrke Penson, retaining many features from c.1660. The present landscape was emparked between c.1590 and c.1650 (Milne 1999, 6). The park walls were completed in c.1774 and enclosed a large landscaped area of over 200 hectares with a small formal garden, walled gardens and a suite of domestic structures. There are some remains of underlying landscapes, including an east-west terrace that may represent part of the Carmarthen-Llandovery Roman road, and traces of roads and trackways that may be Roman and/or Medieval. A Roman milestone and a coin hoard have also been recorded near Dinefwr Castle while sherds of amphorae and Samian ware have been found in the vicinity of Dinefwr Farm (Crane 1994, 6). The central part of the area includes the old parish church of St Tyfi, Llandyfeisant, which has Medieval origins. It is now redundant and used by the Wildlife Trust West Wales; the record ... of 'Roman tesserae' beneath the church appears to be entirely erroneous."

Note:

The architect of Newton House mentioned above, Richard Kyrke Penson, was also responsible for building the impressive lime kilns at the Cilyrychen Quarry in Llandybie in 1857, still visible from the main road, though no longer in use. Modern fertilisers have long put paid to the older practice of spreading lime on farm land.Castle Woods and Llandyfeisant Church

Newton House and most of Dinefwr Park are owned and managed by the National Trust but the modern-day park also includes Castle Woods, Llandyfeisant Church and Dinefwr Castle which comprise the southern edge of the park, overlooking the river Towy. These are all owned by another public body, the West Wales Wildlife Trust, though another public body again – CADW, the Welsh ancient monument organisation – maintains Dinefwr Castle on their behalf.The Castle Woods Nature Reserve has been described as "... one of the most exciting woodlands in South Wales" by no less an authority than Peter Crawford, a senior producer with the BBC's Natural History Unit, in his book 'The Living Isles.' "The woodland is primarily oak and wych elm," he writes. "The shrubs and ground cover are outstanding with cherry, holly, spindle, dog violet and the parasitic toothwort. Lichen communities are of importance and include the rare lungwort. Overlooked by the romantic Castle of Dinefwr the fine old parkland has a herd of fallow deer. The mature trees attract woodpecker, redstarts and pied flycatchers. In winter the water meadows draw large numbers of ducks." It's every bit as good as it sounds. The woods were purchased by the Wildlife Trust West Wales in 1979 and extend for dozens of acres along the steep slopes which rise from the Towy meadows up to the old Dinefwr Castle and to Penlan Park. The main access is from Penlan Park, but it's also possible to walk down the lane alongside the stone bridge over the Towy, following the marked paths indicated by the Badger footprint signs. Before long you'll come across Llandyfeisant Church, which lies in a delightful, sylvan, secluded setting at the heart of the reserve. (The name Llandyfeisant is a contraction of Llan Dyfi Sant – the church of St Dyfi.) This was regarded as the family church of the Lords of Dynevor, but had fallen into near-dereliction by the 1980s. It had ceased being used for worship in 1961 when its font and stained-glass window war memorial were removed to nearby St Teilo Church for safekeeping. This was not the first time, though, that the church had been allowed to fall into a ruinous state, and nor can the restless twentieth century carry the blame alone for the neglect of our architectural heritage, as the following inspection of Llandyfeisant church aptly demonstrates:

LLANDEFOYSAINT

"The Church consists of two aisles, the roof of the north aisle has no tiles upon it, the Timber which has been very good, & still might be of use, is expos'd to rot in the weather. The other aisle is very much decay'd in the tiling. In fair weather the Minister that assists at Llandeilo reads prayers here once every Sunday, but in wet weather he is forc'd to omitt them there being no convenient place in the Church for keeping him or the people dry. No Bible, Common-Prayer Book, Homilies, Canons, Table of Degrees, nor Register Book. My Lord Carbery who holds the Tithes as Tenant to the Bishop of Chester allows 40 shilling a year to the Minister. Question. whether any preaching? I believe not." (From an account of the results of an [ecclesiastical] visitation of 62 parishes within the archdeaconry of Carmarthen, 'A Visitation of the Archdeaconry of Carmarthen, 1710', published in The National Library of Wales Journal 1976, Summer XIX/3, by G. Milwyn Griffiths.)The date of the above 'visitation' (ie, inspection)? July and August of 1710. But by the 19th century the farm workers, retainers and servants of the rebuilt Newton House and Dynevor estate provided a sizeable congregation for Llandyfeisant church, which was completely rebuilt in the late Victorian period, as described in this survey by the Welsh ancient monument organisation, CADW :

"Small stone church of medieval origin but almost entirely rebuilt in later C19, possibly to designs by R Kyrke Pearson, architect of Oswestry who redesigned Newton House for Lord Dynevor. Plan of unified chancel and nave with medieval (?) South aisle set back to left ... Church of moderate architectural interest in an exceptional location at Dinefwr Park. Fine steeply sloping burial ground with old headstones." (St Tyfi's Church, Dinefwr Park, CADW survey number 11108, 24/06/1991)

Llandyfeisant Church is now buried even deeper in the surrounding woods. Date unknown but about 1910. The church has since been restored with the help of unemployed labour from the Manpower Services Commission and served briefly as an information centre and shop in the 1990s, though it is currently locked. We may be a more secular age than back in 1710 but our lack of piety hasn't stopped us caring for our religious heritage any less. A few yards away from the church lie the ruins of an old gamekeeper's lodge, open to the elements now, and untended graves scattered under the steadily encroaching trees lend the scene a melancholy air tinged with a little mystery. Not somewhere for those of a nervous disposition to find themselves as nightfall approaches, either.

1. Introduction

2. The Middle Ages and Dinefwr Castle

3. The Acquisition of the Lands

4. The Dynevor Title

5. Dinefwr Park

6. Policing Rebecca – The 4th Lord and the Rebecca Riots

7. The Twentieth Century and Ammanford

8. Summary

9. Sources6. POLICING REBECCA – THE 4th LORD AND THE REBECCA RIOTS

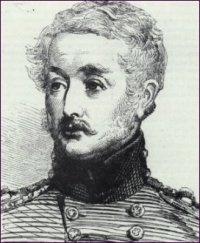

Colonel, the Honourable George Rice Trevor MP, Vice Lieutenant for the County of Carmarthen and from 1852 the 4th Baron Dynevor. (Photo: Nat. Lib. of Wales) As a result of his policing of the Rebecca riots in Carmarthenshire, the 4th Lord Dynevor has a place in Welsh history not accorded the rest of his family. A selection of his letters which have survived in various public archives reveal in some detail his involvement in the dramatic events that unfolded in Carmarthenshire during 1843 and 1844. George Rice Trevor (1795–1869), who became the 4th Lord Dynevor in 1852, was also the local Member of Parliament and Vice-Lieutenant of the County of Carmarthen and it was his responsibility for policing the disturbances. (His father, the 3rd Lord Dynevor, was the Lieutenant of Carmarthen, so it was a family affair in every sense of the word.) After an attack by Rebecca rioters on Carmarthen workhouse in June 1843, George Rice Trevor rushed back from his London residence to take over the responsibility of law and order in Carmarthenshire from his elderly father, a task he undertook with evident relish. And when Rebecca burned down corn stacks on his own Dinefwr estate in Llandeilo he quickly discovered he had a personal interest in the drama that was rapidly developing in his own backyard. And there was more to come, as his biographer in the 2004 Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) reveals:

"Trevor assured a meeting of magistrates at Newcastle Emlyn in June 1843 that he would order troops to fire on the rioters if necessary. The response of the protesters was predictably fearsome: in September 1843, they audaciously dug a grave within sight of Dinefwr Castle, the family seat, and announced that Trevor would occupy it by 10 October. Trevor, however, surrounded by soldiers, survived unscathed." [Mathew Cragoe, DNB, 2004.]

To be on the safe side a detachment of Dragoons was billeted at Llandeilo's George Inn in George Street for almost a year.

The George Rice Trevor letters, relating mainly to the activities of 'Rebecca' in south-east Carmarthenshire and west Glamorgan between 1843 and 1844, allow a picture of the unfolding events to be pieced together. Most of them are addressed to William Chambers junior, who was regarded as a liberal, and was present at a number of the early public meetings held by 'Rebecca'. However, as a magistrate at Llanelli, he also had a close relationship with the authorities, and did his best to stamp out the often violent night-time activities of the 'Daughters of Rebecca'.

The 'Rebecca Riots' is the name commonly given to a series of disturbances and popular protests which took place in parts of south-west Wales during the 1830s and 1840s. At that time, the inhabitants of this rural area were living in considerable poverty as a result of a serious economic depression. Between 1837 and 1841, local farmers endured a series of extremely poor harvests and the prices of their produce fell sharply. At the same time, the farmers faced considerable increases in their outgoings: rents were increased, as well as tithe payments (taxes), poor rates and turnpike tolls. The population had also increased sharply since the beginning of the nineteenth century, placing an even greater strain on this rural society.

By the mid-19th century Britain's already bad roads were being used by ever-increasing wheeled vehicles. Smaller parishes could not afford proper repair and so the 1835 Highway Act was passed, permitting tolls for road maintenance. Turnpike Trusts run by private companies were established and allowed to recover the costs of road building and repair by means of toll charges, plus whatever profit they felt like making. But the rights to collect tolls were auctioned off to the highest bidder and used to maximise profits as well as recuperate costs; with gate-keepers often paid on commission this was a system open to abuse, and abuse there certainly was. Llandybie historian Gomer Roberts gives us the details of such an auction in 1813:

LLANDEILO DISTRICT OF TURNPIKE ROADS

Notice is hereby given that the TOLLS arising at the several tollgates upon the Turnpike road of Ffairfach, Llandebie Gate, with the sidegate thereunto belonging, and the Llanedy Forest Gate, will be LET by AUCTION to the best bidder, at the George Inn, Llandilo, on Saturday, the 4th of September next ... which tolls produce the present year sums hereunder stated, above the expenses of collecting them:Ffairfach and Llandebie Gate with side Gate, £640.

Llanedy Forest Gate, £21.Thomas Morgan, Clerk to the Trustees,

Llandebie, 10th August, 1813'Hanes Plwyf Llandybie' (History of the Parish of Llandybie), Gomer Roberts, page 78 of English translation by Ivor Griffiths, 1986 (our italics.)

Gomer Roberts also informs us that it was seven shillings a week (£18 a year) that the 3rd Lord Dynevor paid his servants on his lands and gardens in 1811 so the income generated by a tollgate could be considerable – and most tollgates came complete with a house for the gate keeper and his family.

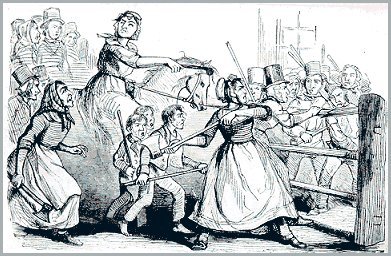

A contemporary print entitled 'Rebecca and her Daughters assembling to destroy a turnpike Gate'. (Nat. Lib. of Wales) The 'Daughters of Rebecca' made their first appearance in Pembrokeshire on 13th May 1839, when a group of men disguised in women's clothes demolished the tollgate at Efail Wen near Narberth and attacks took place again in June and July. The owner of the tollgate was one Thomas Bullin, an Englishman who owned Turnpike Trusts all over southern Britain, from as far afield as east London, Portsmouth, Bristol and west Wales. Bullin was persuaded to pull the Efail Wen gate down and 'Rebecca' disappeared for a while before reappearing in November 1842 when a gate near St Clear's was destroyed. The attacks reached their peak during the summer of 1843, when the authorities decided to send for troops and the Metropolitan Police. By the end of that year the riots had come to an end, and many of the leaders of the movement were under lock and key. Rebecca's main targets to begin with were the tollgates – powerful visual symbols of the economic oppression which many farmers faced. However, the focus of their protests soon shifted to target high-rent landlords, bailiffs, unpopular magistrates, those individuals who were responsible for collecting tithe payments (taxes), and even fathers of illegitimate children. Attacks were also made against a number of workhouses in the area as the protesters expressed their hatred of the new Poor Law of 1834 and the means by which paupers were being treated. The rioters were mostly the small, subsistence farmers who were being forced to pay the tolls, though a number of new industries had been established in this area and coal miners and metal workers joined with the farmers in their protest. Elsewhere in the industrial area of neighbouring Swansea, the much larger Chartist demonstrations were occupying the authorities at the same time, stretching their resources to the limit. (The Chartists – today we would call them Civil Rights Campaigners – also had a wide-ranging political agenda, such as the right to vote, and this worried the authorities even more than the merely economic demands of Rebecca.)

Daughters of Rebecca attacking a Toll Gate. (London Illustrated News 1843) The numerous raids, usually at night-time, were made by men dressed in women's clothing and wigs, with faces blackened to evade identification. The name Rebecca was taken from the biblical verse: "and they blessed Rebecca and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions and let thy seed possess the gates of those who hate them." (Genesis, chapter 24, verse 60.) The leader of each band of rioters was designated as 'Rebecca' and rode a white horse to distinguish him/her from the rest of her 'daughters' (see the above contemporary illustrations). Troops were sent to southwest Wales and some rioters were arrested, although such was the popular support for the protests that convictions usually proved difficult, even after one attack which had left Sarah Williams, the gatekeeper of Hendy tollgate, dead:

"About 2 o'clock, on 9 September 1843, a party of men disguised in white dresses, went to Hendy Gate, about half a mile from Pontarddulais. They carried out the furniture from the toll-house, and told the old woman, whose name was Sarah Williams, to go away and not return. She went to the house of John Thomas, a labourer, and called him to assist in extinguishing the fire at the tollhouse, which had been ignited by the Rebeccaites. The old woman then re-entered the tollhouse. The report of a gun or pistol was soon afterwards heard. The old woman ran back to John Thomas's house, fell down at the threshold, and expired within two minutes. She had received several cautions to collect no more tolls.

......On 11 September an inquest was held before William Bonville, Coroner. Two surgeons, Ben Thomas, Llanelli, and John Kirkhouse Cooke, Llanelli, gave evidence that on the body were marks of shot, some penetrating the nipple of left breast, on in the armpit of the same side, and several shot marks on both arms. Two shots were found in the left lung. In spite of all this evidence the jury found 'that the deceased died from effusion of blood into the chest occasioned, suffocation, but from what cause is to this jury unknown.'" (George Eyre Evans, describing a letter from George Rice Trevor, 13 Sept., 1843.)(For the fates of the various people involved in the attacks on Hendy and nearby Pontardulais tollgates, see the website 'Rebecca in Pontardulais' by Ivor Griffiths.)

The authorities quickly saw they had no hope of convictions in the other Pontardulais incidents if the trials took place locally, so great was the popular support for the Rebeccaites. Thus the tactical decision was taken to move the Pontardulais trials to Cardiff, where it proved easy to secure convictions (the High Sheriff of Glamorgan selected the jury himself) and five ringleaders (including the infamous Sion Ysgubor Fawr and Dai'r Cantwr), were transported to Australia, with others given lesser sentences. (During the year long series of disturbances a total of thirteen people were eventually transported. None ever returned.)

In certain areas like the Gwendraeth Valley, what had started as a movement for reform was hijacked by a much more violent element, and Sarah Williams was its tragic outcome. A far cry from the earlier raids, which had been conducted in a carnival atmosphere (at least for Rebecca and her daughters):

"It was about midnight [on 2nd January 1843] when a large crowd, this time all on foot, dressed in a variety of garments, faces blackened, and armed with the usual array of weaponry, walked up to the gate at Pwll Trap. They halted a few yards short, and the lady Rebecca – stooped, hobbling, and leaning like an old woman on 'her' blackthorn stick – walked up to the gate. Her sight apparently failing her, she reached out with her staff and touched it. 'Children,' she said, 'there is something put up here; I cannot go on.' 'What is it mother?' cried her daughters. 'Nothing should stop your way.' Rebecca, peering at the gate, replied 'I do not know children. I am old and cannot see well.' 'Shall we come on mother and move it out of the way?' 'Stop,' said she, 'let me see and she tapped the gate again with her staff. 'It seems like a great gate put across the road to stop your old mother,' whined the old one. 'We will break it mother,' her daughters cried in unison; 'Nothing shall hinder you on your journey.' 'No,' she persisted, 'let us see; perhaps it will open.' She felt the lock, as would one who was blind. 'No children,' she called, 'it is bolted and locked and I cannot go on. What is to be done?' 'It must be taken down mother, because you and your children must pass.'

......Rebecca's reply came loud and clear: 'Off with it then my dear children. It has no business here.' And within ten minutes the gate was chopped to pieces and the 'family' had vanished into the night. ("And They Blessed Rebecca", Pat Molloy, Gomer Press (1983), pages 42–43.)The acquittal of another Rebeccaite in a different incident disgusted George Rice Trevor, and he revealed his feelings in this letter of 19th July 1944:

"I am sorry to say our Petty Jury disgraced themselves most terribly in acquitting a Rebecca leader, in spite of his own acknowledgment of having been present at the time a Tollhouse was destroyed, on which occasion two witnesses swore he was actively engaged. He said: "I did no more that the others" who, however, pulled the house down amongst them."

George Eyre Evans, who transcribed the Rice letters for the Carmarthenshire Antiquarian Society, describes the incident that so irritated Rice:

"A Rebecca leader was David Evans, who at the Summer Assizes, opened before Sir Robert Monsy Rolfe, at Carmarthen on 13 July, 1844, was tried for being concerned in pulling down and destroying Llanfihangel-ar-Arth Gate on 16 July 1843, and found "guilty of being in the company, but not guilty of demolishing." On Wednesday, 17 July, he was again tried for destroying Gwarallt Gate. The jury, having been locked up all night not agreeing, the Judge ordered the prisoner to be discharged, but told him that he might be called again at the next or any Assizes to be tried for the same offence before another jury."