Dinefwr is of paramount importance in Welsh history as the seat of the Welsh rulers of Deheubarth, the medieval principality of south-west Wales. The rocky crag with its commanding view over the wide Twyi valley may have seen occupation in prehistoric periods, and Roman artifacts have been uncovered from various parts of Dinefwr park. The place-name appears in the Welsh law codes, which suggest that, early in Welsh history, the site was the principal possession of the south Wales royal house. The early importance of Llandeilo as the probable site of St Teilo's monastery gives further weight to Dinefwr's claim to be an early medieval centre of political power. According to legend, the first Dinefwr Castle was built by Rhodri Mawr (Note 1) - King of Wales in the 9th century. By 950 A.D., Dinefwr was the principal court from which Hywel Dda ("The Good") (Note 2) ruled a large part of Wales including the southwest area known as Deheubarth. His great achievement was to create the country's first uniform legal system.

In 1163 the castle was in the possession of Lord Rhys, who ruled over Deheubarth at a time of stability and harmony, a time, moreover, of a renaissance of Welsh culture, music, poetry and law. After the death of this great ruler, conflict over the succession arose between his sons, and thereafter the important castle figures repeatedly in the turbulent years of dynastic struggles between the Welsh princes, and the wars between the Welsh and the English in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. We are told, for instance, that Rhys Gryg, the son of the Lord Rhys, was forced to dismantle Dinefwr Castle by Llywelyn the Great, prince of Gwynedd, who became pre-eminent in the area in the early 13th century. The first building in stone may have followed this supposed dismantling as the circular keep is of a type traditionally dated to this time.

Later in the 13th century the English crown had to respond to the threat of the increasing power of Llywelyn the Last of Gwynedd, and the resulting battle with the Welsh at Coed Llanthen near Llandeilo was a devastating English defeat. Dinefwr at that time belonged to Rhys Fychan and, after his death, to his son Rhys Wedrod. It may well have consisted of the great round keep, the polygonal curtain wall and the round north-west tower of the inner ward, while the outer ward probably contained timber service buildings. (see aerial photo below)

After the death of Henry III in 1272, Edward I came to the throne and within five years had destroyed the power of the Welsh princes. In 1276 an English army under Pain de Chaworth was assembled at Carmarthen, and Welsh resistance crumbled. Rhys Wedrod placed Dinefwr in the king's hands, and from this time the castle remained largely in possession of the English crown. The castle was put into the custody of a constable, and building accounts inform us that repair work was undertaken in 1282-3 when the ditches were cleaned out, the tower, bridge, hall and "little tower' were repaired, a new gate was built and five buildings were erected within the outer ward. Further repairs were carried out in 1326, and it may be that it was around this time that the rectangular hall, projecting beyond the north curtain wall, was constructed.

Two settlements developed in Dinefwr Park - a township in the immediate vicinity of the castle and a "New Towne" near the present day Newton House. "New Towne" was established in 1298 by Edward I to counter the Welsh settlement around the castle. Settled with English families, "New Towne" was granted privileges by Edward, the Black Prince, which did not extend to the Welsh community. Comparatively little was spent on the castle during the remainder of the 14th century, and the great tower is described as being on the point of collapse in a document of 1343. However, it was still able to resist a siege by Owain Glyndwr (note 3) in 1403.

In the 15th century Dinefwr underwent a cultural renaissance reminiscent of Rhys ap Gruffydd's court. Having leased Dinefwr in 1439, Gruffydd ap Nicholas became Deputy Justiciar and gained control of the royal government of south Wales. The King addressed him as a "right trusty and well beloved friend." In 1451 Gruffydd was patron and judge at the Carmarthen Eisteddfod which produced the rules of poetic metre that are still followed today. Medieval poets allude to the family's descent from Urien Rheged, who ruled northern Britain in the Dark Ages, and the Ravens of Urien which were said to have protected Urien's son, Owain, from his enemies. The ravens feature in the coat of arms of Gruffydd's descendants, the Dynevor family. The line of Gruffydd ap Nicholas was united with the last princes of Deheubarth when his son, Thomas, married Elizabeth, daughter of Sir John Gruffydd and descendant of Lord Rhys.

Gruffydd ap Nicholas' grandson, Rhys ap Thomas, and Henry Tudor were both descended from Lord Rhys. In 1485, when Henry Tudor landed at Milford Haven and marched his troops towards the English midlands, Rhys ap Thomas raised an army in support. After Henry's defeat of King Richard III at Bosworth, Rhys was knighted, later appointed Chamberlain of the Principality of South Wales and granted the castle at Dinefwr. He was finally appointed to the post held by his ancestor, Justiciar of South Wales. In the Tudor period, Sir Rhys ap Thomas carried out some alterations, especially to the hall on the north, before abandoning the castle for a new house built to the north, on the site of the present Newton House.

The approach to the castle is from the east, through the defences of the outer ward at the probable site of the outer gatehouse. The defensive bank and deep rock-cut ditch enclose the lower part of the hilltop, where stood the castle's domestic and service buildings. The path continues through the fragmentary remains of the middle gate and long, narrow entrance passage protected by a high wall to the inner gate. Despite considerable alteration during several building phases, the joints of the original large entrance arch can be seen in the masonry. Inside the inner ward, little remains of the gatehouse save for the lower courses of the masonry to either side of the gate passage and consequently the style of this probably later 13th-century structure in unknown. Arrowslits which would have defended the passage from rooms on either side, and the ornate stops for the gates may be seen low down in the stonework. Above this, the masonry has been rebuilt, and, on the east, the ground level has been raised in post-medieval times to form steps to the wall-walk.

The inner ward is enclosed by a high, angular curtain wall, much repaired and equipped with iron railings in recent times to create a safe, pleasant walk. Dominating the interior of the castle is the great round keep on the east, with its battered base. The present ground-floor entrance is a later insertion, and the original door was on the first floor. A trapdoor in the floor probably provided access to the large, dark basement, floored with slabs laid over the bedrock. A larger first-floor window which overlooked the courtyard on the north was blocked during 18th century work on the tower. It is now difficult to know how much taller the keep would have been before it was so drastically modified by the addition of the summer-house on the top, but it may well have had at least one further storey. The summer-house, with its conical roof, became a famous landmark, and it still retains its door and large windows designed to give splendid views over the park.

The curtain wall probably continued around the keep on the east but has now fallen, and the walling on the north-east corner is modern. The circular three-storey tower on the north-west may well have been built by the Welsh princes but the rectangular tower on the north was probably constructed after 1277. It has a latrine on the west side, and a deep basement. The tower and the adjacent rectangular hall, the inner wall of which has now fallen, were substantially modified in the early Tudor period, when the castle was owned by the wealthy and influential Sir Rhys ap Thomas. By this stage, the military significance of the castle was minimal, and comfort and appearance was of greater importance.

NOTES

(1) Rhodri Mawr

Walker 1990; Davies 1990According to legend, the first Dinefwr Castle was built by Rhodri Mawr - King of Wales in the 9th century. It is unavoidable that attention should focus on those Welsh rulers who extended their power over much of Wales in the centuries prior to the Norman Conquest. They foreshadowed the attempts by the princes of Gwynedd in the 13th century to create a unified Welsh state, and they matched contemporary developments in England, and similar, but later, developments in Scotland. So, Rhodri Mawr (844-78) is presented as one who set a pattern for the future. He either ruled or, by his personal qualities, dominated much of Wales.

Chroniclers of his generation hailed Rhodri ap Merfyn as Rhodri Mawr (Rhodri the Great), a distinction bestowed upon two other rulers in the same century - Charles the Great (Charlemagne, died 814) and Alfred the Great (died 899). The three tributes are of a similar nature - recognition of the achievements of men who contributed significantly to the growth of statehood among the nations of the Welsh, the Franks and the English. Unfortunately, the entire evidence relating to the life of Rhodri consists of a few sentences; yet he must have made a deep impression upon the Welsh, for in later centuries being of the line of Rhodri was a primary qualification for their rulers. Until his death, Rhodri was acknowledged as ruler of more than half of Wales, and that as much by diplomacy as by conquest.

Rhodri's fame sprang from his success as a warrior. That success was noted by The Ulster Chronicle and by Sedulius Scottus, an Irish scholar at the court of the Emperor Charles the Bald at Liege. It was his victory over the Vikings in 856 which brought him international acclaim. Wales was less richly provided with fertile land and with the navigable rivers that attracted the Vikings, and the Welsh kings had considerable success in resisting them. Anglesey bore the brunt of the attacks, and it was there in 856 that Rhodri won his great victory over Horn, the leader of the Danes, much to the delight of the Irish and the Franks.

It was not only from the west that the kingdom of Rhodri was threatened. By becoming the ruler of Powys, his mother's land, he inherited the old struggle with the kingdom of Mercia. Although Offa's Dyke had been constructed in order to define the territories of the Welsh and the English, this did not prevent the successors of Offa from attacking Wales. The pressure on Powys continued; after 855, Rhodri was its defender, and he and his son, Gwriad, were killed in battle against the English in 878.

(2) Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good)

Davies 1990; Walker 1990By 950 A.D., Dinefwr was the principal court from which Hywel Dda, "The Good", ruled a large part of Wales including the southwest area known as Deheubarth. His great achievement was to create the country's first uniform legal system. Hywel shared with his brothers lands in Ceredigon and Ystrad Tywi after the death of their father, Cadell, about 909. He united their inheritance in 920, and acquired Gwynedd after the death of Idwal Foel in 942. He married Elen, daughter of Llywarch of Dyfed, and on Llywarch's death in 904 he took over the southern kingdom. In the perspective of the Dark Ages he was a powerful prince, and it may be that later generations borrowed his personal authority to buttress their own power.Like his grandfather, Rhodri the Great, Hywel was given an epithet by a later generation. He became known as Hywel Dda (Hywel the Good), although it would be wrong to consider that goodness to be innocent and unblemished. In the age of Hywel, the essential attribute of a state builder was ruthlessness, an attribute which Hywel possessed, if it is true that it was he who ordered the killing of Llywarch of Dyfed, as some have claimed.

Although contemporary evidence is lacking, there is no reason to reject the tradition that Hywel was responsible for some of the consolidation of the Laws of Wales. Among Hywel's contemporaries there were rulers who won fame as law-givers. The law was Hywel's law, cyfraith Hywel; his name gave to the law an authority comparable with that given to the laws of Mercia by King Offa or the laws of Wessex (and a larger area of England) by King Alfred. He almost certainly knew of them; he was a regular visitor to the English court and in 928, when in the flower of his manhood, he went on pilgrimage to Rome. In later centuries it was claimed that he took copies of his laws to Rome, where they were blessed by the Pope. Tradition also provided details of the circumstances under which the laws were compiled and promulgated.

It was probably the need to give cohesion to his different territories that prompted Hywel to codify the law. He was also successful in defending his territories, for there is no record that they were ravaged by the Vikings during his reign. Neither were they attacked by the English. Hywel adhered to the close relationship with England initiated by his father-in-law, Llywarch of Dyfed, yet it is unlikely that he relished the diminution in status and the heavy demands for tribute which resulted from his association with the kingdom of England. He recognised the facts of power - the power which in his lifetime extinguished the Brythonic kingdom of Cornwall and which brought about the death of his cousin, Idwal of Gwynedd.

Hywel's creation of the kingdom of Deheubarth, survived his death. In 950 it passed to his son Owain. Gwynedd and Powys returned to the line of Idwal ap Anarawd while Glamorgan continued to be subject to its own kings. Although the union between Gwynedd, Powys and Deheubarth was broken, Wales had only three kingdoms after 950, compared with over twice that number two centuries earlier.

(3) Owain Glyndwr

Gwyn A. Williams 1985; Wales: The Rough Guide, 1994No name is so frequently invoked on Wales as that of Owain Glyndwr (c. 1349-1416), a potent figurehead of Welsh nationalism ever since he rose up against the occupying English in the first few years of the fifteenth century. Little is known about the man described in Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part I as "not in the roll of common men." There seems little doubt that the charismatic Owain fulfilled many of the mystical medieval prophecies about the rising up of the red dragon. He was of aristocratic stock and had a conventional upbringing, part of it in England of all places. His blue blood furthered his claim as Prince of Wales, being directly descended from the princes of Powys and Cyfeiliog, and as a result of his status, he learned English, studied in London and became a loyal, and distinguished, soldier of the English king, before returning to Wales and marrying.

Glyndwr was a member of the dynasty of northern Powys and, on his mother's side, descended from that of Deheubarth in the south. The family had fought for Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in the last war and regained their lands in north-east Wales only through a calculated association with the powerful Marcher lords of Chirk, Bromfield and Yale and the lesser family of Lestrange. They thus rooted themselves in the Welsh official class in the March and figured among its lesser nobility.

Glyndwr was comfortably placed. He held the lordships of Glyn Dyfrydwy and Cynllaith Owain near the Dee directly of the king by Welsh Barony. He had an income of some 1200 punds a year and a fine moated mansion at Sycharch with tiles and chimneyed roofs, a deerpark, henory, fishpond and mill. He was a complete Marcher gentleman and had put in his term at the Inns of Court. He must have been knowledgeable in law; he married the daughter of Sir David Hanmer, a distinguished lawyer who had served under Edward III and Richard II. He had served in the wars and retinues of Henry of Lancaster and the earl of Arundel, and served with distinction in the Scottish campaign of 1385.

But he was more than a Marcher. He was one of the living representatives of the old royal houses of Wales, an heir to Cadwaladr, in a Wales strewn with the rubble of such dynasties. Wales in the late 14th century was a turbulent place. The brutal savaging of Llywelyn the Last and Edward I's stringent policies of subordinating Wales had left a discontented, cowed nation where any signs of rebellion were sure to attract support. In 1399-1400 Glyn Dwr ran up against his powerful neighbor, Reginald de Grey, Lord of Ruthin, an intimate of the new king, Henry IV. The quarrel was over common land which Grey had stolen. Glyndwr could get no justice from the king or parliament. This proud man, over forty and grey-haired, was visited with insult and malice. There are indications that Glyndwr made an effort to contact other disaffected Welshmen, and when he raised his standard outside Ruthin on 16 September 1400, his followers from the very beginning proclaimed him Prince of Wales.

The response was startling and may have even startled Glyndwr himself. Supported by the Hanmers, other Norman-Welsh Marchers and the Dean of St Asaph, he attacked Ruthin with several hundred men and went on to savage every town on north-east Wales. There was an immediate response from Oxford, where Welsh scholars at once dropped their books and flocked home. Even more dramatic was the news that Welsh laborers in England were downing their tools and heading for home. The English Parliament at once rushed ferociously anti-Welsh legislation on to the books. Henry IV marched a big army right across north Wales, burning and looting without mercy. Whole populations scrambled to make their peace. Over the Winter, Glyndwr, with only seven men, took to the hills.

But in the spring of 1401 as the Tudors snatched Conwy Castle by a trick, Owain's little band moved into the centre and the south. Once more, popular insurrection broke around them, and hundreds ran to join the rebellion. It was during 1401 that Glyndwr became aware of the growing power of the rebellion as men of higher rank began to defect to the cause. In his letters to south Wales he declared himself the liberator appointed by God to deliver the Welsh race from their oppressors. The English king, Henry IV, despatched troops and rapidly drew up a range of severely punitive laws against the Welsh, even outlawing Welsh-language bards and singers. Battles continued to rage, with Glyndwr capturing Edmund Mortimer, the earl of March, in Pilleth in June 1402. By the end of 1403, Glyndwr controlled most of Wales.

The twelve-year war which ensued was, for the English, largely a matter of relieving their isolated castles. Expedition after expedition was beaten bootless back. Henry IV, beset by Welsh, Scots, French and rebellious barons, sent in army after army, some of them huge, all of them futile; he never really got to grips with it and the revolt largely wore itself out, in a small country blasted, burned and exhausted beyond the limit of endurance. For the Welsh, it was a Marcher rebellion and a peasant's revolt which grew into a national guerrilla war. The sheer tenacity of the rebellion is startling. Few revolts in contemporary Europe lasted more than some months; no previous Welsh war had lasted much longer. This one raged in undiminished fury for ten years and did not really end for fifteen.

In 1404, Glyndwr assembled a parliament of four men from every commot in Wales at Machynlleth, drawing up mutual recognition treaties with France and Spain. At Machynlleth, he was also crowned king of a free Wales. A second parliament in Harlech took place a year later, with Glyndwr making plans to carve up England and Wales into three, as part of an alliance against the English king: Mortimer would take the south and west of England, Thomas Percy, earl of Northumberland, would have the midlands and the north, and himself Wales and the Marches of England. The English army, however, concentrated with increased vigor on destroying the Welsh uprising, and the Tripart Indenture was never realized.

Disaster struck in 1408 when the castles of Aberystwyth and Harlech fell to the forces of the king, and Glyndwr's own family was taken prisoner. The Welsh nation that had existed for four years took once more to the woods with its prince once more an outlaw. Owain, with his son Meredudd, and a handful of his best captains, together with some Scots and Frenchmen, was at large throughout 1409, devastating wherever he went. No one knows what happened to Glyndwr, but, like Arthur, he could not die; he would come again. Henry V, the new king, twice offered the rebel leader a pardon, but the old man was apparently too proud to accept.

What is more remarkable than the civil war that the revolt inevitably became, is the passion, loyalty and vision which came to sustain it. Glyndwr's men put an end to payments to the lords and the crown; they could raise enough money to carry on from the parliaments they called, attended by delegates from all over Wales - the first and last Welsh parliaments in Welsh history. From ordinary people by the thousands came a loyalty through times often unspeakably harsh which enabled this old man to lead a divided people one-twelfth the size of the English against two kings and a dozen armies. Owain Glyndwr was one Welsh prince who was never betrayed by his own people, not even in the darkest days when many of them could have saved their skins by doing so. There is no parallel in the history of the Welsh.

The draconian anti-Welsh laws stayed in place until the accession to the English throne of Henry VII, a Welshman, in 1485. Wales became subsumed into English custom law, and Glyndwr's uprising became an increasingly powerful symbol of frustrated Welsh independence. Even today, the shadowy organization that surfaced in the early 1980s to burn holiday homes of English people and English estate agents dealing in Welsh property has taken the name Meibion Glyndwr, the Sons of Glyndwr.

Since 1410 most Welsh people most of the time have abandoned any idea of independence as unthinkable. But since 1410 most Welsh people, at some time or another, if only in some secret corner of the mind, have been "out with Owain and his barefoot scrubs." For the Welsh mind is still haunted by its lightning-flash vision of a people that was free.

[Note: A referendum throughout Wales in 1999 created a Welsh Assembly which took office in 2000 but its powers are limited to merely distributing money sent to it by the United Kingdom exchequer in London. It has absolutely no law making powers of its own and has been described contemptuously by some as a glorified parish council. Be that as it may, the National Assembly, minus any teeth, seems here to stay.]

SOURCES

Gwyn A. Williams, "When Was Wales," Penguin Books, London, 1985.

Wales - The Rough Guide, Mike Parker and Paul Whitfield, Rough Guides Ltd, London, 1994.

The above articles are from the Castles of Wales website: http://www.castlewales.com/DYNEVOR PARK

Web site: http://www.nationaltrust.org.ukAs we've seen above, the Rhys dynasty once ruled over the mediaeval kingdom of Deheuberth which, at its peak, took in large parts of modern day Carmarthenshire, Pembrokeshire and Cardiganshire with Breconshire thrown in for good measure. All that remains of the mighty Dinefwr lands today, one thousand years later, is the small (though perfectly formed) Dynevor Park in Llandeilo. Crossing our traffic-choked roads, in this no longer rural little town, few today realise how recently our residential surroundings were once just pasture and woodland, criss-crossed by a network of tinkling streams and babbling brooks. Tarmac, concrete, bricks and mortar have since covered the fields with the fabric of an urbanized environment; the streams have been culverted underground and out of sight, now reaching their destinations in the Towy and Cennen rivers undetected by the people who scurry about on top. The history of the mediaeval dynasty of Rhys is very well recorded but less so is what happened to the family after they were dispossessed in 1277 by Edward the First, who finally subdued all of Wales by 1284.

Today's Dynevors claim their descent from these same twelfth century Lords Rhys. The mediaeval dynasty however remained dispossessed for 200 years until a Welsh king, Henry Tudor (Henry the Seventh, who also claimed descent from the Lords Rhys), seized the English throne from Richard the Third in 1485 and restored the lands to the latest member of the family line, Rhys ab Thomas. Rhys had raised an army in support of Henry in 1485 so the restoration of his lands was his reward, as was a knighthood granted him by Henry. The next king however, Henry the Eighth, reverted to type and took the lands back from ab Thomas's grandson, Rhys ab Gruffydd, who was accused of plotting with the king of Scots to overthrow Henry and make himself ruler of Wales. Part of the evidence against him was that he had sought to stress his links with the ancient Welsh kings by adopting the name Fitzurien (still part of the Dynevor family name today.) The charges were preposterous and fabricated but it was Rhys's misfortune to be guilty of a crime greater even than treason in Henry's eyes: owning extensive estates and wealth when Henry was in permanent need of money. Rhys's fate was sealed and he was executed in 1531, having no chance of justice at the hands of a man who would soon behead two of his own wives (Anne Boleyn in 1536 and Catherine Howard in 1542). Henry's daughter, Queen Mary (reigned 1553 - 1558), restored some of the lands to the Rhys family and Charles the First (reigned 1625 - 1649) finally restored all the lands to them (who by now had anglicized their name to Rice). A 19th century historian descibes these events thus:"The Dynevor estates were given by Henry the Seventh to Sir Rhys AB Thomas, and descended with his other possessions to his grandson Rhys AB Gruffydd, from whom, through an act of the most cruel injustice, they again reverted to the crown, in the reign of Henry the Eighth. Rhys's ancestors had been in the habit of occasionally adding AB Urien, or Fitz Urien, to their names, in conformity to the general Welsh practice, in order to show their descent ['AB' and 'Fitz' both mean 'son of'']. This designation, after being disused for some time, was again adopted, probably in a vain frolic, by young Rhys. The circumstance being reported to the king, and being associated with the immense possessions and unbounded popularity of the family, was construed [by Henry the Eighth] into a design to assert the independence of the principality, and to dissever it from the English government. It was also supposed, without the shadow of proof, that this was part of a concerted plan to depose King Henry, and bring to the English throne James the Fifth of Scotland. To increase the absurdity of the whole business, the plot was said to be founded on an old prophecy, that James of Scotland with the bloody hand, and the Raven, which was Rhys's crest, should conquer England. On such frivolous grounds was this young chieftain, himself one of the first commoners in the realm, and connected by marriage with the family of Howard, arraigned for high treason, found guilty, and beheaded.

......On the accession of Queen Mary, his son, Gruffydd AB Rhys, had his blood restored, and received back part of the estates; and Charles the First relinquished to Sir Henry Rice all that were at that time of them in the hands of the crown. The estates thus restored to the family were valued at about three hundred pounds a year; these constitute their present Welsh territories, and are all that remain to them of the princely possessions of their ancestors.

......The house of Dynevor has always held considerable influence in the county [ie Carmarthenshire], and has in several instances furnished its parliamentary representatives. George Rice, who died in 1779, married in 1756 Lady Cecil Talbot, only child of William, Earl Talbot. This nobleman was afterwards created Baron Dynevor, with remainder to his daughter, who, on his death in 1782, became Baroness Dynevor. On the death of her mother in 1787, she took the name and arms of De Cardonel, which are still borne by the family. Her ladyship died on the 14th of March 1793, and was succeeded by her eldest son George Talbot Rice, the present Baron Dynevor [in 1815].(Thomas Rees, The Beauties of England and Wales, 1815. Reprinted in A Carmarthenshire Anthology, edited by Lyn Hughes, Christopher Davies, 1985, pages 107 - 108)The Dynevor Title

The Rhys (or Rice) family may have had their lands at least partially restored in the Tudor and Stuart reigns but the title that once went with them in medieval times was not part of the deal. The modern Dynevor peerage goes back only to 1780 when Charles Fitz Uryan Rice was created the 1st Baron Dynevor (again, anglicised spellings were more in keeping with the fashion of the day so Dinefwr had to go). Walter Fitz Uryan Rice became the 7th Baron Dynevor on the death of his father in 1911 but by 1916 being Welsh had come back sufficiently into fashion for him to change the name Rice by royal assent back to Rhys! (But not before a street in Betws built on Dynevor land had been named Rice Street after him in 1906.)Newton House

An 18th-century landscape park, enclosing a medieval deer park, Dinefwr is home to more than one hundred fallow deer and a small herd of Dinefwr White Park Cattle. A number of scenic walks are available including access to Dinefwr Castle, with fine views across the Towy Valley. There is also a wooded boardwalk, particularly suitable for families and wheelchair users. Newton House, built in 1660, but now with a Victorian façade and a fountain garden, is at the heart of the site. It has two showrooms open to the public, a tea-room which looks out onto the deer park and an exhibition on the history of Dinefwr in the basement. There had been a manor house on the ancestral estate at Dynevor Park since the 15th century but It was in 1775, at the time of the creation of the 1st Baron, that the grounds were remodelled by Capability Brown in the fashion of the time - a carefully-controlled 'wilderness' of sweeping parkland punctuated by groups of towering trees. Stroll back through the deer park and you soon arrive at Newton House (or Plas Dinefwr), the "new' castle. Although the present Newton House dates back to 1660 and Sir Edward Rice - the great-great-great-great-great grandfather of the present Lord Dynevor - the house has substantial 18th-century and Victorian Gothic additions. Newton House has had something of an unhappy recent history. It was sold by the present Lord Dynevor in 1974 and suffered badly, falling into near ruinous disrepair. It was occupied by squatters for many years and was stripped of many of its original features. (No more than two people at a time are allowed on the top floor because the structure has been weakened by the removal of beams and joists for firewood!)Mercifully, both the mediaeval castle and Newton House have recently been restored by Cadw and the National Trust respectively, who now run the park, its buildings and a tea shop. Dynevor Park is also open to the public. Check the National Trust website for opening times, admission prices etc on: http://www.nationaltrust.org.uk. Since being restored to something resembling its former glory, Newton House has become an important feature of Llandeilo's cultural life, providing a superb setting for concerts and exhibitions as well as being licensed for civil weddings. The National Trust acquired the deer park and the outer park at Dinefwr in 1987. Newton House was purchased by the Trust in 1990 having been through several hands since first sold by Lord Dynevor in 1974. The East Drive was acquired in 1992. The generosity of the Heritage Lottery Fund facilitated the purchase of Home Farm and Penparc in 2002 and the site of a Roman fort has since been discovered on Home Farm, so an exciting prospect lies ahead when the site, hopefully, is excavated in the near future (see below). Dinefwr is now 286 hectares in extent (707 acres).

Newton House today in the tranquil setting of Dinefwr Park, Llandeilo

Web Site: http://www.wildlifetrust.org.uk/wtsww/ (then click on RESERVES)

Newton House and most of Dynevor Park are owned and managed by the National Trust but the modern-day park also includes Castle Woods, Llandyfeisant Church and Dinefwr Castle which comprise the southern edge of the park, overlooking the river Towy. These are all owned by another public body, the West Wales Wildlife Trust, though another public body again - CADW, the Welsh ancient monument organisation - maintains Dinefwr castle on their behalf.The Castle Woods Nature Reserve has been described as "….one of the most exciting woodlands in South Wales" by no less an authority than Peter Crawford, a senior producer with the BBC's Natural History Unit, in his book 'The Living Isles.' "The woodland is primarily oak and wych elm," he writes. "The shrubs and ground cover are outstanding with cherry, holly, spindle, dog violet and the parasitic toothwort. Lichen communities are of importance and include the rare lungwort. Overlooked by the romantic Castle of Dinefwr the fine old parkland has a herd of fallow deer. The mature trees attract woodpecker, redstarts and pied flycatchers. In winter the water meadows draw large numbers of ducks."It's every bit as good as it sounds. The woods were purchased by the Wildlife Trust West Wales in 1979 and extend for dozens of acres along the steep slopes which rise from the Towy meadows up to the old Dinefwr Castle and to Penlan Park. The main access is from Penlan Park, but it's also possible to walk down the lane alongside the stone bridge over the Towy, following the marked paths indicated by the Badger footprint signs. Before long you'll come across Llandyfeisant Church, which lies in a delightful, sylvan, secluded setting at the heart of the reserve. This was regarded as the family church of the Lords of Dynevor, but had fallen into near-dereliction by the 1980s. It ceased being used for worship in 1961 when its font and stained glass window war memorial were removed to nearby St Teilo Church for safekeeping. This was not the first time, though, that the church had been allowed to fall into a ruinous state, and nor can our restless century carry the blame alone for the neglect of our architectural heritage, as the following inspection of Llandyfeisant church aptly demonstrates:"LLANDEFOYSAINT

The Church consists of two aisles, the roof of the north aisle has no tiles upon it, the Timber which has been very good, & still might be of use, is expos'd to rot in the weather. The other aisle is very much decay'd in the tiling. In fair weather the Minister that assists at Llandeilo reads prayers here once every Sunday, but in wet weather he is forc'd to omitt them there being no convenient place in the Church for keeping him or the people dry. No Bible, Common-Prayer Book, Homilies, Canons, Table of Degrees, nor Register Book. My Lord Carbery who holds the Tithes as Tenant to the Bishop of Chester allows 40 shilling a year to the Minister. Question. whether any preaching? I believe not." (From an account of the results of an [ecclesiastical] visitation of 62 parishes within the archdeaconry of Carmarthen, 'A Visitation of the Archdeaconry of Carmarthen, 1710', published in The National Library of Wales Journal 1976, Summer XIX/3, by G. Milwyn Griffiths.)The date of the above 'visitation' (ie, inspection)? July and August of 1710! But by the 19th century the farm workers, retainers and servants of the rebuilt Newton House and Dynevor estate provided a sizeable congregation for Llandyfeisant church, which was completely rebuilt in the late Victorian period, as described in this survey by the Welsh ancient monument organisation, CADW :"Small stone church of medieval origin but almost entirely rebuilt in later Cl9, possibly to designs by R Kyrke Pearson, architect of Oswestry who redesigned Newton House for Lord Dynevor. Plan of unified chancel and nave with medieval (?) South aisle set back to left.....Church of moderate architectural interest in an exceptional location at Dynevor Park. Fine steeply sloping burial ground with old headstones." (St Tyfi's Church, Dynevor Park, CADW survey number 11108, 24/06/1991)The church has since been restored with the help of unemployed labour from the Manpower Services Commission and served briefly as an information centre and shop in the 1990s, though it is currently locked. We may be seen as a more secular age than back in 1710 but our lack of piety hasn't stopped us caring for our religious heritage any less. A few yards away from the church lie the ruins of the former vicarage, open to the elements now, and untended graves scattered under the slowly encroaching trees lend the scene a melancholy air tinged with a little mystery. Not somewhere for those of a nervous disposition to find themselves as nightfall approaches, either.

CADW REPORT ON DINEFWR CASTLE AND DYNEVOR PARK

Dinefwr Park and Newton House

GRID REFERENCE: SN 617225

AREA IN HECTARES: 229.20

Historic Background

(http://www.acadat.com/HLC/HLCTowy/area/area195.htm)These background notes have been taken from Professor Ralph Griffiths's recent study (1991) of the castle and borough of Dinefwr, and from the Cadw/ICOMOS Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales (Whittle 1999).

...... It has long been thought that Dinefwr was the seat of the Welsh princes of Deheubarth. Griffiths has demonstrated, however, that this was not the case and that it is likely that nothing of note existed on the site until Rhys ap Gruffydd (Lord Rhys) erected a castle soon after 1163. It is possible that Lord Rhys built a masonry castle, as a reference of 1213 implies stone walls. At this date Lord Rhys's youngest son, Rhys Gryg, was besieged in the castle by two of Lord Rhys's grandsons. It is likely that the round keep at the castle was built by Rhys Gryg between 1220 and 1233. The castle remained in family hands until the reign of Edward I. Extensive repairs and additions were made to the castle by the English Crown in the 1280s. During latter years of Welsh rule a small settlement - 'Trefscoleygyon' or 'vill of the clerks' - developed outside the castle. By 1294 the town of Dinefwr had 26 burgages, a weekly market and annual fair. The end of the 13th century saw Dinefwr become a twin-town. This consisted of an 'old' town on the hill containing 11 Welsh burgesses, and a 'new' town - soon to be called 'Newton' - containing 35 burgesses of mostly English descent. Newton was located some distance away on the site of the later mansion, Newton House. In 1310 the castle, towns and demesne of Dinefwr were granted to Edmund Hakelut and later to his son. The Hakelut family held their position, apart from a short break, until 1360. Repairs to the castle were carried out under the Hakeluts. A survey of 1360 indicates that Newton was a successful settlement with 46 burgesses. A charter was granted to the towns in 1363, but this seems to have marked a high point in the towns' fortunes. The castle and towns were besieged in 1403 during the Glyndwr rebellion. Following the revolt the towns and castle were granted to Hugh Standish. The Standish family had little interest in south Wales, and both the castle and towns went into decline. In 1433 responsibility for the towns and castle was separated, and the towns and demesne were granted to John Perrot. His cousin married Gruffydd AP Nicholas, and so began the long association with the Gruffydd family. By the time that Gruffydd AP Nicholas's grandson, Rhys AP Gruffydd, was attainted of treason in 1531 his family had built a mansion among the ruins of the former town of Newton, although 'Newton' was still marked on Saxton's map of Carmarthenshire of 1578. The age of the towns and castle had come to an end.

...... However, Newton Mansion continued to be occupied by the Rice (Rhys) family and was partly rebuilt between 1595 and 1603, again in c.1660, and in c. 1757-1779, and then in its present form in 1856-1858 by Richard Kyrke Penson, retaining many features from c.1660. The present landscape was emparked between c.1590 and c.1650 (Milne 1999, 6). The park walls were completed in c.1774 and enclosed a large landscaped area of over 200 hectares with a small formal garden, walled gardens and a suite of domestic structures. There are some remains of underlying landscapes, including an east-west terrace that may represent part of the Carmarthen-Llandovery Roman road, and traces of roads and trackways that may be Roman and/or Medieval. A Roman milestone and a coin hoard have also been recorded near Dinefwr Castle while sherds of amphorae and Samian ware have been found in the vicinity of Dinefwr Farm (Crane 1994, 6). The central part of the area includes the old parish church of St Tyfi, Llandyfeisant, which has Medieval origins. It is now redundant and used by the Wildlife Trust West Wales; the record in RCAHMW 1917, 110, of 'Roman tesserae' beneath the church appears to be entirely erroneous.

......Description and essential historic landscape components

Dinefwr character area includes the whole of Dinefwr Park, plus small areas outside which were associated with the estate such as the Home Farm. The park lies on hilly ground on the northern side of the Tywi valley, immediately to the west of Llandeilo town, and achieves a height of over 90 m. Tree-covered slopes rise sharply from the valley floor to Dinefwr Castle which forms, along with Newton House, the two main foci of the park. The castle stands in a commanding position, overlooking long stretches of the valley. The masonry remains mostly belong to the 13th- and 14th-century, and to estate repairs of the 18th- and 19th- century. The castle is currently being conserved by Cadw. Earthworks outside the castle form part of the outer defence, but probably also mark the site of the small town of Dinefwr. Newton House, the main residence of the Dinefwr estate, provides the second focus in the park. Nothing now remains above ground of the Medieval town, Newton, on which the original mansion was built. The current house dates to the mid 17th-century, but had a new facade built in the 1850s in a Gothic style. The house and most of the parkland is owned by the National Trust. A fine collection of stone-built service buildings arranged around a courtyard lies close to Dinefwr House. Other elements of the gardens and park such as a walled garden, icehouse, dovecote and ponds survive. The 18th century park retains much of its planting. Individual trees, clumps, and more extensive stands of woodland survive. The open character of the park remains - especially the deer park on the western side - though wire fences divide the eastern part of it into large enclosures of pasture. The southeastern corner of the park - Penlan Park - has been municipalised and laid out with tarmac paths. The isolated and redundant Medieval church of Llandyfeisant lies in the area. Those field boundaries that surround the park are earth banks topped with hedges.

......Recorded archaeology mainly relates to the parkland landscape and its features, including a rabbit warren, but underlying features include a possible Bronze Age ring ditch. Roman archaeology includes a milestone, possible roads and tracks and a coin hoard. Features relating to the Medieval settlement of Newton probably underlie present enclosures.

......Dinefwr Park contains many distinctive buildings, and with the garden is listed as PGW (Dy) 12 (CAM) in the Cadw/ICOMOS Register of Parks and Gardens of Special Historic Interest in Wales (Whittle 1999). The Medieval Dinefwr Castle is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and a Grade I listed building. St Tyfi's Church, Llandyfeisant, heavily restored in the 19th century, is a Grade II listed building. Dinefwr (Newton) House, the summer house, and the inner and outer courtyard ranges are Grade II* listed while the ha-ha, fountain, dairy cottage, dovecote, deer abattoir, icehouse, home farmhouse, corn barn and byre/ stable range are individually Grade II listed (9 in all). A bandstand lies in Penlan Park.

......Dinefwr park is a distinct character area and stands in sharp contrast with the surrounding farmland and with the urban setting of Llandeilo.LLANDEILO'S ROMAN FORT DISCOVERED

In 2003 an exciting find was made in the grounds of Dinefwr Park which may in time eclipse even the Medieval castle in importance. It has long been known there was a Roman fort somewhere in Llandeilo: the question about its existence has not been 'if' but 'where'. The Romans built forts every fifteen miles or so to enable their troops to be deployed swiftly in case of local disturbances. There is a Roman fort in Llandovery and another one thirty miles west at Carmarthen, so there had to be one in Llandeilo, equidistant from both. It had been thought that Llandeilo's fort would be nearer the river Towy, but four dinari (Roman coins) found in a field on the Dinefwr Estate shifted the search further inland from the river bank.

Gwilym Hughes of the Cambria Archaeology Trust, the body responsible for the archaeological heritage of West Wales, writes in the Summer 2003 edition of their newsletter, 'Cambria Archaeology':

A complete funeral urn, dated to the early first century AD, unearthed during the summer 2005 archaeological dig. "During an archaeological survey commissioned by the National Trust of their estate at Dinefwr Park Llandeilo, the exciting discovery of a Roman military fort was made by Stratascan, a geophysical survey team used by Cambria to assist in the survey. This work has been supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund.

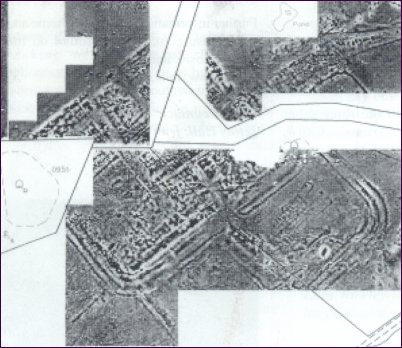

...... Geophysical survey produces a radar-like picture of features beneath the ground surface. What is even more exciting about the Llandeilo find is that there appear to be two forts on the same site, as well as a civilian settlement and other related features, including a Roman Road and a possible Roman bathhouse site. It is thought likely that the first fort dates to about AD 74, the time of the Roman conquest of Wales. [The Romans landed in Britain near Dover in AD 43, so they had reached Llandeilo in just 30 years]

...... It has a possible area of 3.9 hectares, which would make it one of the largest Roman campaign forts in Wales and may have housed a Roman legionary detachment. A second, smaller fort seems to have been built on the same site after the conquest and a small settlement grew outside its gates. The shadow of the first fort can be seen in the lower half of the image produced by the geophysical survey (below). The settlement outside the gates can also be seen in the upper right-hand quarter of the image.

...... Archaeologists will hopefully be able to carry out some excavation in the near future to try to begin to properly date and understand the features which are so clearly visible on the image shown here."(Click on www.cambria.org.uk for the Cambria Archaeology website which contains more details, including the July 2005 excavation.)

From June to July 2005 a three week archaeological dig of the Roman fort was undertaken as part of Channel 4's 'Big Roman Dig' TV project. On the first day an early first century AD funeral urn was discovered (see photo above). There appear to be two overlapping forts plus a vicus, or civilian settlement, dated from 75 AD to 120 AD.

2003 Geophysics of Llandeilo's Roman Fort. The curved and other lines are the various perimeter ditches and wall bases just under the field's surface. The shadow of the two forts can be seen in the lower part of the image produced by the geophysical survey (below). The settlement outside the gates can also be seen in the upper right-hand quarter of the image. The white areas in the image are parts the surveyors couldn't access.

The above geophysics map is from the Cambria Archaeology newsletter, No 2, Summer 2003.

Date this page last updated: September 28, 2010