AMMANFORD CASTLE

CASTELL RHYDAMANNo, gentle reader, you haven't misread the title above, for in the twelfth century there was indeed a castle in what is now Ammanford, on the site of the modern-day Cartref Day Centre in Tirydail Lane. Sadly, the ravages of time, amply aided and abetted by man, have been particularly unkind to Ammanford Castle as nothing now remains of its past splendour except for a twenty foot high mound, or 'motte', now completely overgrown, and some evidence of the perimeter ditch, or 'bailey' discernible only to the trained eye of the archaeologist or historian.

Ammanford Castle was of the type known as a 'motte and bailey', some 68 of which can still be seen in Dyfed alone. This design was first introduced by the Normans after their conquest of England in 1066 but was occasionally imitated by the Welsh. This makes it difficult, indeed often impossible, to ascertain who built some of these structures, there usually being no written evidence to come to the historian's aid. But lack of direct evidence has never deterred the dedicated historian who often turns detective instead, enlisting the help of the archaeologist, the scientist and just about anyone else who can help unravel the tangled thread that leads back into the distant past. Fortunately, modern science has provided a fiercesome array of techniques for the historian and archaeologist to make use of. The archaeologists are usually the first to turn up, their main tool in the detective work being the exploratory trench. A JCB removes the top soil before the the finer instruments such as picks and shovels, sieves, trowels and brushes are brought out. It's at this stage that the basic structures of a former building can be uncovered and any artifacts unearthed. It may be only some fragments of pottery or nails or other small, seemingly insignificant items that come to light but these are usually enough to date a site pretty precisely (Yes, we're all watching the 'Time Team' on television now).

In the larger or more important site, matters don't always stop there. The botanist can be called in to investigate pollen seeds found in earth or water, often coming up with that holy grail for any self respecting historian – a date; the dendrochronologist takes a soggy lump of wood, counts rings under a microscope and after consulting an international data base can also suggest a date; the geophysicists sticks his probes in the ground to detect what structures lie buried beneath, or the physicist can give a date based on the radioactive decay of carbon 14.

Taking our lead from this we shall do something similar and fall back on works by other authors, the first being a booklet produced by CADW, the Welsh Historic Monuments organisation responsible for maintaining the rich heritage of our past (Cadw, in Welsh means 'to keep'). The following is taken from 'A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales, Dyfed', by Sian Rees, published by CADW in 1992, from the chapter entitled 'The Age of the Castle'.

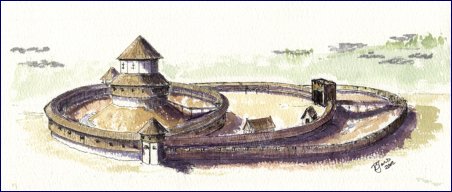

Motte and Bailey Castle Artist's impression of a Motte and Bailey Castle. The 'Motte' was built on a mound with an encampment below defended by a 'bailey' which was a ditch and perimeter wall. If the 'bailey' was breached under attack the defenders withdrew into the motte as the last line of defence. Ammanford castle was of this type. "During the first years after the Norman Conquest, the south Welsh prince Rhys ap Tewdwr seems to have succeeded in maintaining his rule in Deheubarth (the medieval principality of south-west Wales). In return for recognition by the Normans, he paid a tribute to William the Conqueror who marched through south Wales in 1081, ostensibly as a pilgrim to St. Davids, but in reality to establish his overlordship in the area. After Rhys's death in 1093, the Normans made a renewed effort to take control of the accessible southern part of southwest Wales. A series of lordships were established so that the Norman Marches in Wales eventually spread in an arc from Chester to Chepstow in the east to Pembroke in the southwest Each Norman lord built a castle at a key strategic point in his lordship to establish his supremacy and to act as the seat of his government, and, from here, he ruled in what amounted to virtual independence, subject only to the overlordship of the distant English crown.….. Early in the 12th century the first Welsh castles were built in what was known as 'pura Wallia' (pure' or non-Norman Wales), which retained its separate identity for 200 years until the reign of Edward I......

Apart from a few masonry structures constructed at important Norman strongholds such as Chepstow in south-east Wales, the castles which played so important a part in the Norman Conquest were earth-and-timber fortifications which could be cheaply and quickly erected where and when the need arose. Two types of these early castles are known: 'mottes' and 'ringworks'. Mottes were massive conical mounds of earth often 10 m in height, surmounted by a wooden keep or tower. The mounds were surrounded by a ditch and palisade, and a drawbridge over the ditch controlled access to the keep. This was a brilliant plan for strength and ease of construction, but the living quarters were very cramped and uncomfortable. An additional fortified area known as a 'bailey' was often added in order to increase the space available for buildings such as the kitchens and bakehouses, barns and stables, essential for the daily life of the Norman lords.

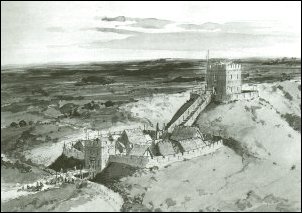

Ringwork Castle The ringwork was a variation of the motte and bailey where the domestic buildings were simply protected by a circular earthen bank and ditch, usually strengthened by a timber palisade, and a strong wooden gate to protect the entrance. In Dyfed some 68 mottes and 30 ringworks survive, most of which lie in the more fertile areas of Norman settlement. The castles which proved to be best sited, at the place where the 'caput', or capital, of the lordship grew up, were rebuilt in stone and gradually developed in sophistication and size. The earthwork castles that remain to our day as simple mounds are the sites that were abandoned as no longer necessary."

(Source: 'A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales, Dyfed', by Sian Rees, published by CADW in 1992, from the chapter entitled 'The Age of the Castle'.)

There are some, however, whose researches lead them to believe in Ammanford Castle being of Welsh and not Norman construction. The following argument is made by Roger Turvey in an article for the Amman Valley Historical Society.

Ammanford Castle/Castell Rhydaman

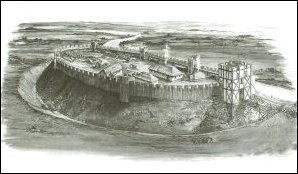

Unbeknown to many of its citizens, Ammanford boasts a fine example of one of the six hundred or so earth and timber castles that once dominated the medieval Welsh countryside. Located in the grounds of Tir-y-Dail house the earthen remains of the site lie hidden beneath thick undergrowth, yet were they to be revealed it is doubtful whether they would attract the attention of a public whose image of the castle is firmly fixed upon the likes of Carreg Cennen. Nevertheless, in its own day the construction of a castle at Ammanford was every bit as significant, if less sophisticated, as those built at nearby Carreg Cennen and Dinefwr less than half a century later. Indeed, the fact of its existence may lead us to suggest that far from being thought a modern settlement with its roots firmly planted in the late nineteenth century, the military occupation of the Amman valley was most likely accomplished some seven hundred years earlier in the mid-twelfth century. To be precise in fixing the date of the castle's foundation is impossible for, like the majority of these former medieval strongholds, Ammanford has no recorded history, its existence confirmed by its remains alone. Nevertheless, this fact should not deter the historian from considering its likely function and importance for as the late Professor T. Jones-Pierce said, 'history cannot proceed by silences; the chronicler of ill-recorded time has none the less to tell his tale'. Although conjectural, it is possible to offer a considered hypothesis regarding the date of Ammanford's foundation, the identity of its founder and its raison d'etre.

...... Despite the late Mr. Cathcart-King's mistaken belief that Amrnanford was a ringwork (an error from his initial survey of 1963 partially corrected in his monumental work Castellarium Anglicanum published in 1983), there can be little doubt that it was in fact a motte and bailey castle. This fact is confirmed in a detailed survey of the site published by the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in 1917 and by close inspection of the remains made by the author in 1984. That said, only excavation can reveal the truth, or not, of this belief The site of Ammanford castle boasts an impressive motte, standing some 20' high with a diameter of 65'. Traces of a narrow bailey some 60'-80' in length have been detected despite disturbance of the site due to landscaping (which may also account for the motte's mutilation). Although the timber structures and defensive pallisades have long since perished, the impressive size of the motte's remains (which probably gave rise to Mr. King's mistaken description) would suggest that Ammanford may be counted among the more significant of the 43 known castle sites in Carmarthenshire. Certainly, its size reflected its important strategic location in the extreme southern portion of Cantref Bychan occupying a salient position at the northern tip of the common frontier of the lordships of Gower and Cydweli (See Map below). The construction of a castle at this point, close to the confluence of the rivers Amman and Llwchwr, along whose banks ran the ancient commotal borders of three lordships, may be viewed as less the product of accident and more one of design. It may thus be inferred that Ammanford was charged with the task of clearly delineating and defending this vulnerable frontier for its master, the lord of Cantref Bychan. The identity of its founder, the lord of Bychan, rests between a member of the Norman families of FitzPons and Clifford, masters of the lordship from c. 1115 to 1158, and again briefly between 1159-62, or from among the descendants of Rhys AP Tewdwr (k. 1093), the last king of Deheubarth. Although inconclusive, the evidence would seem to point to a native lord as the founder of Ammanford castle, more particularly, Rhys AP Gruffudd AP Rhys AP Tewdwr (c. 1132-97) better known to posterity as the Lord Rhys.

Medieval Wales administrative borders – Ammanford Castle was in the Commote of Iscennen in Cantref Bychan (in white), Kingdom of Deheubarth. The Cantrefs of Cydwely and Gower are also shown in white with Ammanford Castle near the common border of the three Cantrefs.

......What grounds can be advanced for its construction by the Lord Rhys? During the Norman occupation of Cantref Bychan (c. 1115-58, 1159-62) the only castle of note within the lordship was Llandovery, there is no reference to any other castle before 1203 (i.e. Castell Meurig, Llangadog). If Ammanford was a twelfth-century foundation it indeed stood on the very southern edge of Cantref Bychan but by the following century the frontier had shifted further south across the Amman to include the maenor of Betws, a part of the lordship of Gwyr (Gower). To prevent further border encroachments the lord of Gower constructed the simple stone structure known as Penlle'r Castell (built in the late thirteenth century) upon Betws mountain, virtually on the new frontier. If we accept that Ammanford was built to mark and defend the southern approach to Cantref Bychan its most likely builder was a native lord who would wish to deter incursions from Gwyr and Cydweli which remained almost exclusively under Norman control in the twelfth century. A Norman lord of Bychan would regard the Welsh of Cantref Mawr a greater threat and would have sited a fortress on the northern boundary along the river Tywi to complement Llandovery. It was only after the removal of the Welsh threat in the thirteenth century that marcher lords could indulge in the luxury of border disputes (this may account for the origin of the term 'striveland' used in the early seventeenth century to describe the area between the river and stream of the Amman and Cathan valleys). Ammanford's timber and earthwork construction – a common feature of the twelfth century – stands in stark contrast to Penlle'r Castell's masonry which is indicative of the sophistication of thirteenth-century border castles to whom, in a less hostile environment, greater resources, skill and technology could be made available. Moreover, Ammanford's location was more in keeping with Welsh rather than Norman defensive strategy, a strategy based upon the river frontiers of the twelfth century.

...... Ammanford may well have served as but one of a number of earth and timber castles utilised by the Lord Rhys to define and defend his resurgent, if fragile, kingdom. In a desperate attempt to maintain the territorial integrity of his growing domain in the 1160s, the Lord Rhys sought a cheap and relatively swift method of defence thus the motte and bailey castle suited both his means and current strategy eg. he maintained such fortresses on the Dyfi and Teifi rivers at Aberdyfi (in Penweddig) and Cilgerran (in Emlyn) respectively. However, by the early 1170s events had conspired to promote a more harmonious and, more importantly, secure relationship with the king, Henry II, and his Norman neighbours. Being confirmed as rightful lord of Cantref Bychan by an agreement in 1171, the Lord Rhys, in all probability, abandoned these once essential border fortresses; henceforth, until 1189 when war was renewed, his frontiers were to be defended by treaty and diplomacy. The majority of such castles in Wales were disposable assets erected to serve a particular purpose and abandoned when that purpose had been realised or resolved. Therefore, Ammanford may only have been in regular use for a little less than a decade, between circa 1162 and 1171, which may account for its obscurity. Certainly, there is little to indicate that the founder of Ammanford had attempted to establish the means for long-term castle support such as one finds at Llandovery with its borough and church or at Carreg Cennen with its Maerdref or vill of bond tenants (called Trecastell). In short, Ammanford's primary role was one of military defence not civilian settlement.

......It is sad but true to say that the history of Ammanford castle is unlikely ever to be written. In the absence of documentary and archaeological evidence, even the latter has its limits, historians will continue to rely on conjecture and speculation to flesh out what would be an otherwise painfully thin history of the site. Ammanford's secrets will remain closely guarded. (Roger Turvey)As Roger Turvey points out above, David J Cathcart King in his 1966 survey misinterpreted Ammanford Castle for a ringwork structure, but his field notes for that survey give a good description of the site as well as the sorry condition ('hatefully overgrown') it has fallen into:

Ammanford, Carms, 153/624125

The site of this castle is just S. of the railway station, in the grounds of Tirydail House, at the edge of the bluff or step to the flood-plain of the Loughor river, perhaps 12 ft high; this protects the W. side of the position. Elsewhere, all is level, The advantage of the site is not obvious.

...... Tirydail House was presumably a gentleman's residence, and the ditches of the inner ring have been filled in towards the S. (where the scarp is also cut back) and the E., the sides near the house. The main ditch survives on the N., and is carried round on to the W. as a mere step on the general slope.

...... Beyond the ditch on the N. is a narrow crescent shaped bailey with no bank – a feature that at once suggests masonry defences, as the bailey has little or no advantage in height over the ground outside it. Close examination, here as elsewhere, is very difficult; brambles are everywhere, and the orphanage which is now housed in Tir-y-dail house does not run to enough outside help to clear them.

...... The ring itself is hatefully overgrown. It seems to be a ringwork, and not just a mutilated motte. The cup is deep, probably down to natural level (Class A), and there is no sign of attack from without. The surrounding bank is level, and fairly wide, to the best of my recollection. There are numerous large water-worn pebble.Dimensions

Diameter impossible to measure, but I paced an approximate semicircle of approx 120 feet, which suggests a diameter of about 75 feet. Height: Scarp (E) 10 feet, no ditch.

Scarp (N) 14 feet, c/s (rear of bailey) 8 feet.Inner Cup 8 – 10 feet deep at a guess. Scarp on W Still 14 feet to step, about 8 feet of natural slope below. Bailey Ditch About 8 feet deep. The most recent examination of the site was in June 2002 when an exploratory ditch was dug on an area of the grounds planned as a car park for the Day Centre. Sadly the findings were disappointing, with three post holes of uncertain date and a few pottery fragments from the 17th century being the only finds.

Tirydal House/Cartref

Whatever happened on that site in Ammanford's distant past, we do have a clearer record of its use in more recent times for which we will next enlist the help of Mr W T H Locksmith and his "Ammanford – Origins of Street Names and Notable Historical Records", pages 242 - 247. (Published by Carmarthenshire County Council in 1999 as part of their millennium celebrations).

As previously mentioned, a settlement existed on this site from a very early period of time but the first substantial records of ownership of land date back only to 1774, when Lord Dynevor commissioned a land surveyor – Mathew Williams – to prepare a map of the farm holding, which at that time was in the region of some 100 acres, bounded on the east by what is now College Street, to the south by Wind Street and Penybanc Road and by the River Loughor to the west.

In later years the property appears to have been leased or rented to Thomas Wright Lawford who, by all accounts, in 1841 was regarded as a progressive farmer, introducing new agricultural and horticultural techniques such as the "Cow Vinery" (taking advantage of animal heat to grow hanging fruit). His advanced ideas were chronicled in the "Cottage Gardener" and other publications on 'Model farming'. Within a short period of time he rented two other adjoining farms – Dyffryn and Myddynfych – which enlarged his holding considerably. It is possible that he overstretched himself in this enterprise, as records show that he was forced into bankruptcy, having to sell all his chattels at a public auction held on the 28th of August 1855 – furniture, books, dairy utensils, hurdlemaking, thrashing winnowing and corn-crushing machines etc, all coming under the hammer. This would, presumably, have been his reason for emigrating to Baltimore, USA, in that year where, according to a legend within his family, he introduced the English sparrow to the USA. Whoever did take that insignificant little bird across the Atlantic, in the short time since that day the 'English' sparrow has spread throughout the entire Americas in much the same way as the American grey squirrel has spread throughout Britain. Not so insignificant a bird after all. (See 'Almost Like a Whale, the Origin of Species Updated', by Steve Jones, Doubleday 1999, page 242). May we not be frivolous for a moment and imagine all those little American sparrows chirruping away in the avian equivalent of Welsh, and with an Ammanford accent at that? And perhaps rename it the Welsh sparrow in the process?

Thomas W Lawford seems to not have confined his activities to horticultural matters, founding a branch of the 'Total Abstinence Movement' in Ammanford, as this newspaper item from the Carmarthen Journal of 3rd November 1854, reports (the florid, heavily punctuated prose style with its profusion of stock phrases was common for the times):

PRESENTATION OF A MEDAL TO THOMAS WRIGHT LAWFORD ESQ.

On Wednesday evening, the 1st inst, a public meeting was held at Brynmawr Schoolroom, near Cross Inn, Llandybie, for the purpose of presenting Thomas Wright Lawford, Esq., with a silver medal as a mark of respect by the working classes. The Rev. John Richards, Incumbent of Bettws, occupied the chair. After the meeting was opened, a very interesting lecture was delivered by the Rev. Thomas Levi, Ystradgynlais, on "Total Abstinence", when the chairman rose on behalf of the working classes, and read the following address:-

"The Humble Address of the Working Classes of Cross Inn,

to Thomas Wright Lawford, Esq., Tyrydail.""Sir, We, the working classes of Cross Inn, beg most respectfully to testify the high sense we entertain for the solicitude with which you have uniformly regarded our best interests. We have witnessed with admiration your disinterested labours to establish our 'Horticultural Society', which, by diffusing among its members a spirit of generous rivalry, conduces so materially to the improvement of our gardens, affording also valuable pecuniary aid, the premiums obtained by many of the competitors sufficing to pay the rent on their cottages. We would also, Sir, advert to the noble, and successful, efforts you have made to institute in our village a 'Branch Total Abstinence Society,' and especially to the fact of yourself being the first to make the plunge. We feel we need not dilate on the benefits which this society has conferred on our land, – thousands of fathers clothed, and in their right mind, sitting at the feet of Jesus, – the songs of joy and gladness resounding from now happy homes, in which the Christian Church gratefully unites, loudly proclaiming its happy influences. In accordance with the above sentiments we hereby most humbly and respectfully beg your acceptance of a silver medal, as a small token of our appreciation of your kind and condescending services, looking forward, however, for their commensurate reward, and the accomplishment of our wishes to the resurrection of the just." (Cross Inn, Nov. 1st, 1854)

......On our medal being presented to Mr. Lawford, he returned thanks with a feeling speech, – which was loudly cheered throughout by the multitude. The medal bears the following inscription:- "Presented to T. W. Lawford Esq., Tyrydail, by the working classes of Cross Inn, for his exertion to promote their domestic comfort and intellectual advancement."

...... (Note: Cross Inn was the original name for Ammanford, which only changed to that name in 1880. Brynmawr Schoolroom was on what is now Brynmawr Lane, leading to All Saints Church, itself not built until 1915.In the above report, the chairman of the meeting – the vicar of Bettws – quite confidently includes himself among the "Working Classes of Cross Inn", but by what authority seems unclear. Amongst those present were the vicars of Betws, Llandeilo, Milo, Cwmamman and Ystradgynlais (five in all), two drapers, a grocer, an ironmonger, a postmaster, four people labelled 'Esq.' and an assortment of 'Mr', 'Mrs' and 'Misses', producing the slight suspicion that this might have been a trial run for Dylan Thomas's 'Under Milk Wood'.

It's also noteworthy that although there were five vicars present, not one non-conformist minister makes an appearence, from which we can assume that the audience was also church going. This is strange, to say the least, as the only places of worship in Cross Inn at that time were all non-conformist chapels. Church worshippers of the village would have to wait until St Michael's was built in 1885; until then they had to attend services at nearby Betws or Llandybie churches.

At some time during this period the Tirydail House was completely renovated and turned into a small country manor; the grounds were extensively landscaped, trees planted, secluded walks along with an artificial ornamental lake formed. It is said that these works were preparatory to occupation of the residence by one of Lord Dynevor's daughters but this never materialised.

On the 1881 Census records, Mr John Brodie (a Scotsman), along with his two sisters, Miss Mary Agnes Brodie and Mrs Mary Player, are shown as the residents of the property. Mr Brodie was described as a 'farmer', employing seven labourers and four women servants, farming a holding of 335 acres. The Farm Bailiff – Mr William Hutchins – occupied a tied cottage known as "The Bothi" ('Bothi' is a Welsh word for 'cottage') and the Gardener, Mr William Jones, resided at 'Brynmawr Cottage', situated in Brynmawr Lane. Brynmawr Cottage has since disappeared but the Bothi, just across the road from modern-day Cartref, is not only extant but is still occupied and in use as a domestic residence.

After the death of Mr Brodie, Mr William Nathaniel Jones, an Auctioneer and Registrar of Births and Deaths, took up residency for a short period of time, along with his wife and three children, Charles Norman, Florence Margaret and William Harold, terminating the tenancy in 1892, when the family moved to 'Dyffryn House'. These three children were to give their names to 'Norman Road, 'Florence Road and 'Harold Street' which were built by their father just a little later to house the employees of Tirydail Tin Plate works, which he owned.

In 1899, Mr David Richards, a Justice of the Peace and a High Sheriff of the County, who was involved in the tinplate industry and at one time sole owner of the 'Dynevor Tinplate Works' at Pantyffynnon, leased the house, (residing there until his death in 1937). The farmland was retained by the Dynevor Estate with large areas absorbed in housing developments.

During the 1939/45 War, Tirydail House was requisitioned by the Army and, for a short period of time, became the billet of the 206 Coast Battery, 17th Coast Regiment of the Royal Artillery, before leaving on the 15th of March 1941 for North Africa. During the fall of Tobruk on the 20th of June 1942 the Regiment was captured by Field Marshall Rommel 's Army, its soldiers ending up as prisoners of war in Italian and German Camps. The 206 Coast Battery was the only service unit to be stationed in Ammanford during the War. [The author of this web site must declare an interest here, as his father was stationed in Tirydail House on the outbreak of war and was one of those captured in Tobruk, spending the duration of the war in prison camps.]

One Dr A. Harper purchased the property in 1946 restoring the house to a private residence and also converting part of the accommodation into a radiographic clinic.

Next, Carmarthenshire County Council acquired Tirydail House for conversion into a children's home, officially opened in May 1953 by the Rt. Hon. James Griffiths M.P. and renamed 'Cartref'. Two Matrons were in charge of the orphanage for the next 25 years of its existence – first Miss Nancy Jones (who retired in 1970), succeeded by Miss Enid West. The intake of children fell significantly in the 1970's, resulting in the County Council closing the establishment.

In direct contrast to the care of the young, 'Cartref' next took on a new role when, in March 1982, it was re-opened as a Day Centre, where the elderly and handicapped could receive daytime supervision, occupational therapy and treatment.

The hum of arrows in the twelfth century has been replaced by the somewhat louder hum of traffic in the twenty first. Modern motorists, unaware they are driving past such a historic site, will also be unaware there might be even more destruction in store for what little is left of the old place. That future, waiting inscrutably in the wings, could well be Carmarthenshire County Council who closed the social services day centre in 2005, though leaving the motte untouched if still 'hatefully overgrown'. What plans the council has for the site are yet to be revealed. For the moment though its secrets are still there to be unearthed, literally, as whatever has survived 800 years of erosion by the elements and disturbance by humans lies buried underground. Perhaps those who would predict the future for this very ancient part of Ammanford should first ponder the old proverb "the time to come is no more ours than the time past".

A useful web site is Cambria Archaeology at http://www.acadat.com

Sources:

– 'A Guide to Ancient and Historic Wales, Dyfed, The Age of the Castle' by Sian Rees, published by CADW in 1992.

– 'Ammanford Castle/Castell Rhydaman, Roger Turvey.

– 'Ammanford – Origins of Street Names and Notable Historical Records', pages 242 - 247, by W T H Locksmith, published by Carmarthenshire County Council in 1999 as part of their millennium celebrations.