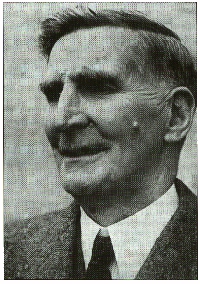

DAVID REES GRIFFITHS

(AMANWY)

1882 – 1953

The story of the self-educated miner is a familiar one for those of us who were born and grew up in the countless mining areas of Britain. They were familiar figures in our streets, chapels, working men's clubs, even our own families. They may have worked in the local mines but many were extremely well-read and informed, often through such organsations as the Workers' Education Association, but also through their own reading. Their chapels and working men's clubs provided libraries which were often better than those provided by their local councils. Much of their reading from the 1930s was political, for many libraries of the working men's clubs subscribed to the Left Book Club, founded in 1936 by the publisher Victor Gollancz with a deliberate left-wing programme until its demise in 1948.

But Marx, Engels, Lenin and Keir Hardie were not the only authors' names who could be heard on the lips of these people; they were usually familiar with the works of Shakespeare and other literary figures as well. And in a Welsh-speaking area like the Amman valley, poetry was a dominant passion, especially in Welsh. For every school, chapel and village held its annual eisteddfod in which the most-coveted prizes were for poetry competitions. The visual proof of success for the winners was usually a carved bardic chair, an impressive object to show off to friends and family, but for their more immediate needs a sum of hard cash often accompanied the chair. The prize money could be considerable; around 1900, £5 (worth about £400 in 2009) and £10 (about £800) were common cash prizes accompanying the chairs, a valuable supplement to the meagre wages of miners like Amanwy.

There were some, however, who felt that competing in eisteddfodau just for the prize money had a harmful effect on the quality of the poetry that was written. Such was the view of another Amman valley coalminer-turned-bard, Watcyn Hezekiah Williams, whose bardic name was Watcyn Wyn. Watcyn Wyn had played the 'eisteddfod game' very successfully for many years but he eventually decided to turn his back on competition once and for all. Although he was as keen as anybody else in the pursuit of prizes he realized, at last, that the influence of the eisteddfod on the literary standards of the time was damaging. He accused poets of looking first at the prize and then at the set theme. He expressed this in some sarcastic lines:

The bard sings his love song

for the prize, not for the girl;

today silver and gold are more alluring

than the charms of love and the smiles of a gentle lover.So great was the desire to win in some poets that they would even steal from each other's work. In the poem 'Plagiarism' Watcyn Wyn refers to this sin:

They steal from everyone except themselves, poor souls;

They would even steal from there if there were something to be found.These collier-poets like Amanwy, Watcyn Wyn and countless others are now all long dead, of course, along with the culture that once nurtured them. But to a man, they had one concern for us children of the post-war generation. For we, unlike them, had been given a free state education, with opportunities to go all the way to university and beyond. That one concern was for us to grasp the opportunities for education and advancement that had been cruelly—and unfairly—denied them, as it had been denied all the generations of the working class before us.

For education for all is one of the most recent arrivals in human history, one that arrived in Britain only after the horrors of World War Two had abated in 1945. A new Labour government was elected in May that year, committed to a major overhaul of British society and industry, with the education system amongst its prime targets for radical improvement. Before then, the state provided free education only up to the age of thirteen; after that, the vast majority of working-class children were ejected from their warm schools and into the harsh realities of the workplace. In the Amman valley that usually meant either the coal mines or the tinplate industry for boys or, for girls, the menial work of domestic service or shop assistants until marriage and home meking beckoned. Any education a child received after they left school was entirely up to them, which in reality meant nothing, as few families could afford the fees for a child to continue in school beyond thirteen or—more importantly—the loss of wages incurred. But a tiny number of individuals did achieve a high level of educational achievement through their own determination; this is the story of one such person.

David Rees Griffiths was born in Betws on November 6th 1882, the fifth child of the ten born to William and Margaret Griffiths. He was an older brother of Labour MP James Griffiths, the first Secretary of State for Wales.

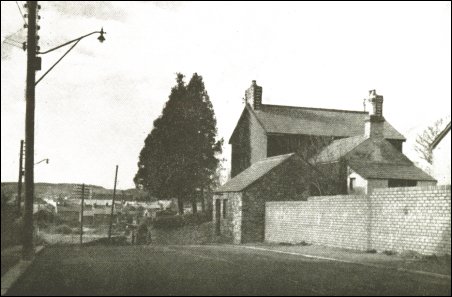

The smithy and home of the William Griffiths and his family in Betws village Amanwy's father William was the local blacksmith and their home was the little village smithy on Betws Square overlooking the river Amman and Ammanford town. (When he embarked upon his literary career in adult life, David Griffiths took the bardic name of Amanwy after his native valley.) The conventional role of the blacksmith had changed radically with industrialisation and mining. No longer did he mainly shoe horses or repair agricultural equipment, for a major part of his trade now was repairing the tools of the local miners. These were the days when miners bought all their own tools and equipment. When the mining industry was nationalised in 1947, the workforce were provided with their picks and shovels, boots, lamps and other necessary items. Not so when Amanwy went underground. His brother Jim Griffiths MP, who also went down the local mine as a boy, has left a vivid picture of life in Betws and Ammanford, and the role played by the local blacksmith. In his autobiography, Pages from Memory, (J. M. Dent, 1969), he described their father's job:

"The village of the 'Beads-house' [ie Betws] had by now been merged with the bigger village across the river to become the township of Ammanford. The world was beginning to discover the value of anthracite coal and new mines were being opened. The smiths' old customers, the farmers, were getting fewer so that Father had to adapt his skill to new tasks—the sharpening and tempering of the colliers' mandrels and the making of hobnails for the colliers' pit boots. This meant changing the working hours at the smithy—for the colliers would bring their tools at the end of their shift, around five in the evening, and they had to be ready for the next morning. To enable the job to be done in the winter months the boys of the family were recruited in turn for duties at the smithy—holding the candle while father sharpened the tools on the anvil, and holding the sharpened tools in the 'bosh', a tub of water into which the red-hot mandrel would be plunged and held until it was 'tempered', fit to cut the 'stone coal' in the 'little vein'. On Saturdays we became the collectors, going around the cottages to gather in the money for the work done during the week." (p5)

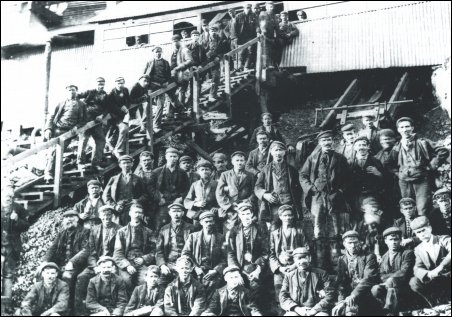

Difficult as it is to believe it now, children at that time went down the mines or into the equally horrific factories as young as twelve years of age. (Only fifty years earlier the age had been as young as eight.) In keeping with that practice Amanwy started work at the recently opened Ammanford Colliery No. 1 (Gwaith Isa'r Betws, or Betws Lower Works) in 1894. Like his brothers and sisters before him he attended the local primary school but his schooldays at Betws Board School were cut brutally short, as were those of hundreds of thousands of children of the working class. Thus began his working life down the mine as a collier's boy at wages of a shilling and two pence a day. Some years later Amanwy recalled the trepidation with which he awaited his first day at the mine:

"I slept but little the night before my big adventure but I had to hide my tears and roll up my sleeves like every other lad in the district." [3 March, 1938]

After just two years at the Betws Colliery Amanwy had to seek work elsewhere. Another local coal mine, Drifft y Parc, provided work but the conditions there were far worse than those at Betws. Drift y Parc proved to be the worst mine he ever worked at, despite his experience of many other mines in the area, and it left bitter memories even sixty years later:

"If ever there was a Dartmoor of a place for a boy collier it was Drift y Parc. It had been opened by a small company with very little resources and limited financial backing, by people who sought to make a quick fortune in the industry. Conditions were primitive to say the least, the memories we boys endured have left deep scars on our souls. The slavery was enough to break a youngster's heart and it must be remembered that colliers in those days were not as careful or as kind to the lads in their care as the colliers of today." (Written 29/01/1953).

Education for a child thirsty for knowledge in those times came, not from schools, but from their own efforts and the assistance of their family and local community. Books were borrowed from wherever they could be found, and early on Amanwy was driven by a thirst for knowledge that never left him. Again we must turn to Jim Griffiths to describe the world of learning in which Amanwy grew up—indeed, the only world of learning that was available to the children of the working class in those days:

"I count myself fortunate to have been nurtured in a home which had its own world of books. Father had his Bible commentaries and his radical journals. My eldest brother had religious books by Henry Drummond, Jeremy Taylor and Thomas a Kempis. The brother who became the bard [ie Amanwy] had his tomes of Welsh poetry and prose and his sheafs of manuscripts. The next to me had his own world of boys' papers, three each week: Marvel, Pluck and Union Jack. And in due time there was added my own collection of pamphlets and periodicals. Most important of all in their influence on me were the two journals which came to our home because we were dissenters. These were the denominational weekly 'The Examiner' and its companion, 'The Christian Commonwealth'. Both had one feature in common, the weekly sermon by the minister of the Congregational Cathedral (the City Temple), the Rev. R. J. Campbell. These weekly sermons suddenly threw two bombs into our family circle, the New Theology and Socialism. This set us all arguing at home, at chapel, and in the mine and mill." (Pages from Memory, p 10-11)

Amanwy was fortunate also in that his father's blacksmith shop provided a meeting place for similar minded people from the area who would gather there to discuss all the issues of the day, whether they be political, religious, literary or whatever. His father was a keen debater on political and religious matters, causing his younger brother Jim Griffiths to describe the smithy as the local parliament, Many years later Jim Griffiths would provide a detailed description of the village 'parliament' in his autobiography 'Pages from Memory':

The smithy was, of course, the village parliament, where the local politicians gathered and argued about religion and politics and the parish council and more distant institutions. My father ruled his parliament with the same iron grip with which he held the colliers' tools ... He was a dissenter (Annibynwr) by denomination and a Radical in politics. His heroes were Gladstone, Tom Ellis and David Lloyd George – in that order. By the time I came to hold the candle the order had changed, for it was the time of the Boer War and Lloyd George was fighting valiantly against the enemy on his own side as well as the ancient enemy, the Tories.

..... The village parliamentarians were sustained by the two radical weeklies Llais Llafur ('Labour's Voice') and Tarian y Gweithiwr ('The Workers' Shield'). One of the backbenchers would read the editorials to the 'House' and then the debate would continue until the last tool had been tempered and the 'House' stood adjourned. I cannot recall a single division [ie vote] taking place in my time – the smith would sum up and that was that. My last recollection of the village parliament is of the burning indignation at Balfour's Education Act of 1902 – with the injustice of asking dissenters to pay for the schools of the alien Church. This carried us out of the smithy to the road to march to the demonstration at Ammanford where the great man himself – David Lloyd George – was the orator. So it was that I began my training in politics, demonstrations and all that goes to the making of a politician – on the way from one 'parliament' to another. (Pages from Memory, (J. M. Dent, 1969), p5-6)(Note: the issue above of asking non-conformists to pay for church affairs occurs in the essay on Watcyn Wyn in this section, where Llandeilo chapel worshippers became indignant at being asked to pay for the upkeep of the church clock and the church bell ringers. Watcyn Wyn dismisses their complaints in a satirical poem on the affair.)

Clearly the parliamentarian in Jim Griffiths had chosen to describe his father's smithy, somewhat jocularly, as a miniature parliament but Amanwy appears not to have shared his brother's interest in politics quite so much, even though Amanwy's poetry and prose express similar socialist tendencies to those of his brother. Still, outrage at injustice can be felt just as strongly by those who are its victims, without having to take up political cudgels against it.

In 1908, while Amanwy was employed at the nearby Pantyffynnon Colliery, an incident occurred which was to have a profound influence on the future course of his life. On January 28th of that year a terrible explosion occurred and Amanwy was among six men who were badly injured, suffering serious burns to his body.

Worse still, two miners were killed, and Amanwy's brother Gwilym Griffiths was one of them. During the two months that Amanwy was bedridden with his injuries a serious interest in literature took root. Assisted by the books he had inherited from his dead brother, the long hours of his recovery were spent reading and writing his own poetry. There were many poets in Betws at the time who became regular visitors to his home and who encouraged him to continue with his efforts. Two of these poets were keen Eisteddfod competitors, John Harries (Irlwyn) of Maes y Betws and Gwilym Jones (Myrddin) of Glan Nant y Ffin. (An English translation of a poem by Irlwyn can be found at the end of the essay on Jim Griffiths in this section).

Another local poet who encouraged him was Gwili, who had won local prizes and a National Eisteddfod literary prize for his poetry. Gwili was the bardic name of John Jenkins who was the headmaster of Gwynfryn School in Ammanford which had been founded by another local poet of some renown, Watcyn Wyn (click HERE for the essay on Watcyn Wyn in this section). Gwili took a keen interest in Amanwy's poetry and Amanwy became Gwili's assistant as secretary of the Ammanford Cymmrodorion Society after his recovery (cymmrodorion are fellows). The Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion was formed in 1751 by Lewis Morris (1702-65) and his brother Richard (1703-1796), and received a Royal Charter in 1951 on the occasion of its bicentenary. Their website is on: www.cymmrodorion1751.org.uk from which we learn: "Established for the encouragement of Literature, Science and the Arts as connected with Wales, the society continues to promote the practice and development of literature, the arts and sciences insofar as they are of special interest to Wales, the Welsh people and those interested in Wales.")

Recognition as a writer was not long in coming for Amanwy. Between 1910 and 1923 he won a total of 52 carved oak chairs at provincial Eisteddfodau. A book about the history of eisteddfod chairs published in 2009 includes a photograph of a chair Amanwy won in 1915 in Tumble and has this to say about Amanwy's 52 chairs:

Amanwy's bardic chair won at an eisteddfod in Tumble in 1915. It is currently on display in Ammanford library. The chair at Tumble in 1915 was one of a number made with simple basic frames having large shaped cross-sections or plaques forming the back and joining the front legs. This was in essence a 17th-century northern Italian and Spanish style and gave the opportunity for prominent lettering amid a carved background.

.....It was won by Amanwy (David Rees Griffiths), an Ammanford collier who was brother to James Griffiths, MP for Llanelli. This was the heyday of the eisteddfod, with regular events in every locality, and many gave chairs to poets, usually for free verse. In the National eisteddfodau, the chair is awarded only for poems written in the strict cynghanedd metres and a crown is the prize for the winning poem written in the free metres, but in local eisteddfodau, where the contestants were usually of a lower standard, the rules were relaxed and a chair was given for prize-winning poems in the free metres. A large and handsome carved oak chair, holding pride of place in your living room is, after all, a much more desirable object to show off to your visitors than a small crown.

.....Amanwy assisted Gwili as secretary to the Ammanford Cymmrodorion Society and was typical of those poets that continually entered contests across Wales and won numerous prizes. By the age of thirty-five he had won twenty-five chairs and by 1923, six years later, he had won fifiy- two. Amanwy won three over Christmas in 1922—at Cilfriw (near Neath), Glanaman and Pwllheli. In 1925 he won another three on Whit Monday—at Aberffraw, Pontyberem and Llandovery; these were all with different poems, netting £16. 16s (about £800 in 2009) in addition to the chairs.

.....Amanwy never won at the National, although he entered several times for the crown and his poems were commended. Three of his chairs, at Anglesey, Manchester and Glyn Ceiriog, had been adjudicated by T. Gwynn Jones.

.....A plaque was placed on the Tumble chair after Amanwy's death, describing him as 'Glowr; Gwerinw; Bardd'. (Miner, One of the People, Poet), adding ‘ Minnau a garaf mwyach Werin yr hen Gwm' (Henceforth I love the People of the old Valley).[From: The Bardic Chair (Y Gadair Farddol), Richard Bebb and Sioned Williams, Saer Books, 2009, page 129.]

An anthology of his work was also published, a collection of poetry entitled Ambell Gainc (a song or two). The anthology was not only popular but was also praised by Welsh literary critics of the day. His reputation as a writer grew, as did the respect for the miner whose recovery was attributed to his determination to succeed. He took up journalism, writing a column in the Amman Valley Chronicle which was eagerly awaited each week, perhaps because of its often outspoken articles. This was written in Welsh and entitled Colofn Cymry'r Dyffryn (column of the Welsh speakers of the valley). He used the pseudonym Cerddetwr meaning 'one who walks or wanders aimlessly'.

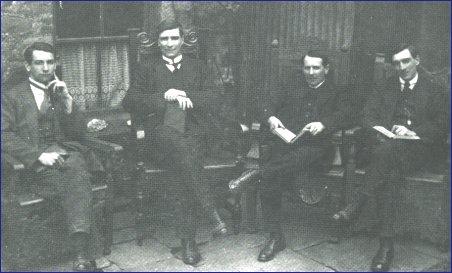

Four of Amanwy's 52 Eisteddfod chairs. The occupants include Amanwy (2nd from left) and his brother James Griffiths, later MP and first Secretary of State for Wales (right). Here is an example of the columns written by Amanwy for the Amman Valley Chronicle. This particular piece got him into hot water as did many others, but he was a man of principle and continued to speak his mind.

He begins by chastising the teachers of Ammanford for their indifferent attitude towards the Welsh Language:

"I remarked upon this at a St. David's Day function here in Ammanford recently. Someone got to his feet and harshly condemned me, adding that I had no grounds whatsoever for making such remarks. The following morning, I stood by the school gate and listened to the teachers and the gentleman concerned chattering in the yard. Not a single word of Welsh was heard. And if I may say so, I found it highly amusing when I heard the wives of some of our foremost Welsh preachers, at the meetings of the union of Welsh Independents here last summer. Some of these ladies believe that speaking English is indispensable to their class. This is the only way they can show that they belong to the elite. Poor, insecure little things! But keep your ears open in the shops and on the streets and even in the lobbies of our chapels and you'll hear the swankiest English ever created and such English! Indeed, I have heard better English spoken by the tribesmen of Karoo."

('Colofn Cymry'r Dyffryn', 10th November 1927).Often outspoken, he displayed the same dislike of injustice as his brother. By all accounts he had a fiery temper and could not restrain himself from passing comments on an injustice whatever its source. The plight of ordinary workers caused him great concern and it was an issue close to his heart. Although he had a great love of the Welsh language and culture, Amanwy was never convinced that the Nationalism would improve or try to improve the lives of the working class.

Education was the way he believed young miners could better themselves and he encouraged them at every opportunity. He held literary classes at his home and pupils included fellow colliers, John Harries of Betws, John Roberts the elocutionist from Glanaman and two young colliers, Gomer Roberts and David Mainwaring.

While his brother Jim Griffiths went from success to success in his political career, Amanwy's life was accompanied by personal tragedies, despite his success as a writer. A history of Betws, Betws Mas o'r Byd, describes the tribulations he suffered at this time:

"In 1910, his wife Margaret died of Tuberculosis (TB), leaving two small boys, Ieuan and Gwilym (named after his own dead brother). He remained a widower for eight years until he met Mary Davies of Dunvant, whom he married in 1918.

..... Three years later his 12-year-old son Ieuan died from a prolonged illness. In 1927 it transpired that his remaining son, Gwilym, was also suffering from Tuberculosis. The family was advised to take him to South Africa where the climate may have improved his condition. Gwili and Amanwy's other close friends launched a fund to send father and son to South Africa. They spent a month in Cape Town before moving on to the mountains of the Karoo. Amanwy continued to write articles for the Amman Valley Chronicle, inspired by the struggles of the African tribes. He returned home two months later but Gwilym did not return for another three years.

..... The following year Gwilym took up his scholarship place at Lampeter College. His future looked promising until his third year at college, his health deteriorated and he was forced to return home. He died in 1935 at the age of 27. Amanwy was devastated by the loss of his son. In a letter to Gomer Roberts he wrote the following words: "My dreams have been blown like chaff in the wind!"During all his personal tragedies Amanwy continued helping others. Betws Mas o'r Byd again:

Amanwy had been appointed the caretaker of the newly opened Amman Valley Grammar School in 1928. He was extremely popular with the students. In spite of his sadness he continued to encourage the budding young poets and took an interest in all those who wished to educate themselves. Some of the youngsters never forgot his influence over their lives, Gomer Roberts was one. Gomer Roberts became a distinguished historian of Calvinistic Methodism and Amanwy played a part in assisting him to achieve his goal. In 1923, Gomer Roberts won a scholarship to a college in Birmingham. Such was the camaraderie between colliers in those days, Amanwy devised a scheme to help him financially. He assembled an anthology of poetry written by local miners.

..... The anthology was called O Lwch y Lofa meaning from the dust of the pit. The volume of verse included the work of Gomer Roberts and Amanwy himself A thousand copies were sold and the proceeds were given to Gomer Roberts to assist him in college. Amanwy was described as a rare exception among the miners of the Amman Valley. A poet with far more ambition than his fellow poets, his verse was considered of a much higher standard than that of his contemporaries.

The poets of O Lwch y Lofa: Top row (;eft to right): Gomer M Roberts, Gwilym Stephens. Bottom (left to right): David Mainwaring, S. Gwyneufryn Davies, Amanwy, Jack Jones. (Note: Gomer Roberts later wrote a history of Llandybie parish "Hanes Plwyf Llandybie" which has been used many times for this web site).

The last years – recognition at last

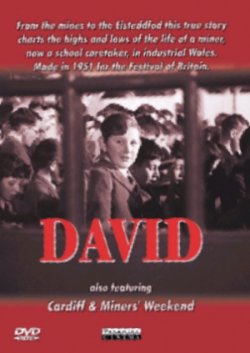

The last two years of Amanwy's life at least brought him some recognition. Amanwy had never climbed to the great heights of his brother but was successful enough to have a film made relating the story of his life, the story of David the poet and miner and the tragedies that stalked him. The film, entitled David, was made in 1951 by Paul Dickson for the Festival of Britain, and it brought much recognition to the village and Ammanford. It told the story of the typical Welsh miner of little education, who through determination had climbed the social ladder through literature. The film was written by Aneurin Talfan Davies and the type of miner depicted was based on Amanwy and he played the leading role. It was shown 22 times in Ammanford and it brought Amanwy some fame and recognition; he received letters from all over the world. In 2001 the British Film Institute put on a season of films that had been commissioned for the Festival of Britain, including David. The review of David, below, shows how the film still stands up to scrutiny, fifty years after it was made:David: the film

This article by Sarah Easen, Cataloguer, BUFVC and Curator of the NFT Festival of Britain Season and Exhibition, (May–October 2001) highlights the spectrum of films made specifically for the Festival of Britain celebrations in 1951. Over twenty films were produced including Paul Dickson's film David.

From March 2005 David is available from Panamint Cinema on both video and DVD. Running time 72 min. Click HERE for ordering details. The Festival of Britain, from 3 May to 30 September 1951, hoped to provide some respite from the ongoing affects of the Second World War by celebrating the nation's past achievements in the arts, industry and science as well as looking ahead to a future of progress and prosperity. It also marked the halfway point of the century, a natural time to take stock and examine advances in British society. Britons were 'promised a year "of fun, fantasy and colour," an interlude of "fun and games" after a long run of austerity' by the Director General of the Festival, Gerald Barry. Thus, the role of the film was integral to the Festival of Britain. It covered all three areas of concern—the arts, industry and science— and Britain's role in international film culture had already been established by the growth of the British Documentary Movement since the 1930s. The Festival of Britain therefore seemed a natural place to showcase British film production. The London-based Festival of Britain site at the South Bank featured a purpose-built film theatre, the Telekinema 2 for big-screen public television broadcasts and the showing of specially commissioned Festival films.

..... Paul Dickson's film David sought to embody the spirit of Welsh society through the small south Wales community of Ammanford. Dickson had won a British Film Award in 1950 for his first film 'The Undefeated' (1950) and used the same technique of combining drama and documentary in' David'. The film has a complex flashback narrative structure with a cast of local people, often playing their real-life roles. The local school caretaker, on whose life the film is based, plays the protagonist, Dafydd. Told firstly through the eyes of Ifor, a young villager who has returned for a visit, the viewer learns that the caretaker was an inspiration to him.

..... The second flashback takes us through the caretaker's life beginning with his first job in the mine, which ends when he is injured in a pit accident. As he says, his life parallels that of the Welsh nation, "most men of my age in Wales can tell the same story, getting coal was the thing, it was our wealth and in a way our destiny". The people of Ammanford are stoic through their hardships; again the character of Dafydd represents this. A poem he has written after the death of his son from tuberculosis is entered in the National Eisteddfod; it receives an honourable mention but does not win. The theme of the Eisteddfod "he who suffers conquers" is an equally fitting epithet for Dafydd, his community and the nation of Wales. The film ends with an ex-pupil from Dafydd's school, now a nationally respected scholar, returning as guest of honour to the school prize giving. Although he is a now a respected national figure, the scholar is still a part of the smaller community he was nurtured in. The most important factor, as the voiceover states, is being "worthy of our heritage, our country, Wales". David was uniformly praised for its naturalism and humanism. 'Monthly Film Bulletin' said it combined "intelligent shaping of the narrative with an unrestrained realism. Gavin Lambert, writing in 'Sight and Sound', thought it a "success for all concerned" and it was listed as one of the magazine's 'Films of the Month.' 'Today's Cinema' described it as "the first really live and human film made for the Festival", adding that it was "always restrained, dignified and extremely moving". 'Variety' commented that despite "some too-evident artiness in the production technique, this short film registers with a moving sincerity." 'Kinematograph Weekly' thought it a "charming and efficiently presented authentic life story of a Welshman." 'The Amman Valley and East Carmathen News' concurred, stating that the caretaker's "life story is [a] true reflection of the integrity of character that is a feature of the Welsh nation".['Film and the Festival of Britain 1951' by Sarah Easen, May 2001, © Manchester University Press, commissioned for 'British Cinema in the 1950s: A celebration' edited by Ian MacKillop & Neil Sinyard' (isbn 0-7190-6489-9)].

DVD/Video of David

From March 2005 the film is available from Panamint Cinema on both video and DVD. Running time 72 min. DVD: £19.99; VHS: £16.99. Prices include P&P worldwide. Click HERE for ordering details.In the winter of 1953, his health began to deteriorate and he was admitted to Morriston Hospital. He continued to contribute to his newspaper columns. He wrote his last article on December 17th 1953. The last line reads: "I must end here for the light is to be put out". Amanwy died ten days later, December 27th 1953. Although proud of his achievements, the one prize that fuelled his ambition had eluded him, the chair of the National Eisteddfod.

Amanwy had never kept secret his preferences and prejudices: he was described by some as a controversial character. Through his love of words he championed the cause of the anthracite miner and continued to do so long after his retirement from the industry. His life, it is fair to say, brought him more downs than ups but the hardships and heartache failed to crush his spirit. Today his writing is an important source of information and for future generations it will be invaluable. He reveals the riches and poverty of everyday life in a Welsh industrial valley. He wrote in-depth accounts of the anthracite coalfields and with his use of language painted a picture of what life was really like in the dusty mines of yesterday.

NOTE:

Much of this article is taken from Amanwy by Dr Huw Walters of the National:Library of Wales, Aberystwyth. For the full version of this article as printed in The Carmarthen Antiquarian, vol 35, 1999, click: Amanwy, by Dr Huw Walters.Sources:

— Amanwy by Huw Walters in 'The Carmarthenshire Antiquarian', Vol. 35, 1999, pages 89-102.

— Pages from Memory, Jim Griffiths MP, published by J M Dent 1969.

— Betws Mas o'r Byd, published by Betws History Group 2001.

— Film and the Festival of Britain 1951 by Sarah Easen, May 2001, © Manchester University Press, commissioned for 'British Cinema in the 1950s: A celebration' edited by Ian MacKillop & Neil Sinyard (isbn 0-7190-6489-9). .A charming example of Amanwy's poetry is Yr Hen Gwm (The Old Valley), with its depiction of the arduous life of the collier and the even more difficult business of courtship.

The Old Valley

(Yr Hen Gwm)An icy morning fog that chills the bone,

A bitter wind that lifts the mist on Garth,

These my companions on this wintry day.

And as I cross the valley to the mine,

The freezing river Amman now my guide,

My heart beats louder than a hammer's thud.A nervous question forms upon my lips –

"All safe and well today down at the face?"

The fireman nods, the level beckons to ....(note 1)

The longest mile a man will ever walk,

My feet like lead before the shift begins.

The jacket off, and then my shirt and vest,

And pick and shovel go to work at last

Before my raucous singing fills the air.Sings ...

"There's a girl from the Hendy I'll win by and by

.........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

Her song is a sweet as the lark's in the sky

........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

Her step is as light as the hind on the hill;

The gold of her hair from the sun takes its fill;

But her tongue is as sharp as the salt of the sea.

.........Heave ho! Out with the coal!There's a collier from Betws with a look in his eye

..........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

And an ache in his heart, heaving sigh after sigh

..........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

Heaven for him is to wait for his love

By the ash trees of Hafod, at the gate of the grove,

And to taste of the honey that's found in her kiss.

........Heave ho! Out with the coal!On the day of All Saints, with its mist and its rain

.........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

A ring on her finger my love will proclaim

..........Heave ho! Out with the coal!

At the foot of the Twrcan, in a small cottage there, ....(note 2)

We will weave into dreams all the hopes that we share

And change into song all life's woe and life's care.

..........Heave ho! Out with the coal!(Translation made for this website)

Notes:

(1) Fireman: an official responsible for safety underground. As many accidents are caused by gas explosions, he is known as a fireman (not to be confused with the fire brigade personnel of the same name). A shift was not allowed underground until the fireman had made his inspection and given permission to proceed.

(2) Twrcan: A hill on the Black Mountain above Glanamman. On the map it is named Tair Carn (Three Cairns) but is pronounced Twrcan locally.

In 1993 a new industrial estate was built on the recently demolished site of Pullman's factory, New Road. All the schools of Ammanford were invited to submit names for the new site and the winning name, Parc Amanwy, in memory of Amanwy, came from two pupils of nearby Parc y Rhun Primary School.

Amanwy had been caretaker of Amman Valley Grammar School from 1928 until his retirement and when the school became a comprehensive in 1970, one of the school houses was called Amanwy in his memory.

(The other houses in the new comprehensive school were also named after local poets, namely Watcyn, Llwyd and Nantlais. The houses in the former Grammar School had been named after the Welsh princes—and warriors— Hywel, Glyndwr, Llewelyn and Dewi. An improvement in whom we should regard as role models, perhaps).

Date this page last updated: August 23, 2010