ALAN WATKINS

FLEET STREET JOURNALIST

(3rd April 1933 - 8th May 2010)

Born in 1933 in Tycroes, Alan Rhun Watkins was one of Britain's best known political journalists, a trade he plied for over fifty years. Educated at Tycroes Primary School and Amman Valley Grammar School, at just seveteen he was awarded an exhibition (ie, a scholarship) at Queen's College, Cambridge University. In his four years at Cambridge (1951-1955) he read law while also becoming chairman of the University Labour Club and being elected to the committee of the Cambridge Union.

After Cambridge he did his two years' National Service in the RAF from 1955-1956 as Flying Officer Watkins of the Education Branch, teaching airmen English to GCE level. His initial ambition was to go the Bar and he qualified as a barrister in 1957 but never practised. In the 1950s there was little prospect of any young man making even the barest living in his early years at the Bar. So Watkins, who had married at the age of 22, took an academic job instead, becoming a research assistant at the London School of Economics for two years from 1957-1959.

But neither academia nor the law were to his liking; during his time at the London School of Economics he first dabbled in journalism, contributing an article to the Labourite Socialist Commentary. Its subject was Parliament's high-handed treatment of the Sunday Express editor, John Junor, who had been summoned to the House of Commons to apologise for criticising Members of Parliament. Junor had suggested that MPs got special petrol rations during the Suez crisis of 1956, small beer compared to revelations in 2009 about MPs exorbitant expenses claims, but enough in those days to force an apology from anyone who dared suggest our parliamentarians were corrupt. Perhaps not surprisingly the piece appealed to Junor sufficiently for him to offer the then 26-year-old Watkins a job on The Sunday Express in 1959, which included a six months stint in New York as that paper's American correspondent. Whether Junor realised it or not, he had set Watkins on his course for life. By this one act, Watkins was spared the dreary round of magistrate's courts, council meetings and all the other lowly chores that normally serve as the apprenticeship for aspiring journalists; for him, it was straight in as a weekly columnist, a start that few, if any, journalists ever get.

Of his upbringing, his obituarist in the Guardian newspaper writes:

"Watkins was born in the Carmarthenshire village of Tycroes, north of Swansea, the adored only child of teachers, themselves clever offspring of mining families. His mother, Violet, spoke no Welsh, but his father, David John (DJ) Watkins, did not read English until he was 12 and was not always easily understood when visiting London. But he was highly erudite, largely self-taught and sceptical of worldly pretence.

.....Watkins Senior had worked as a mines labourer before qualifying to teach, and suffered a professional calamity when he lost his headship for some unspecified offence. It embittered him. But young Alan grew up in a bookish household, Carlyle and Macaulay on the shelves, the News Chronicle and Observer through the letterbox, encouraged to talk public affairs as well as watch rugby with his father. On matters of grammar and taste, though, he deferred to his mother. After she died at 92, he felt ashamed that he had not rescued her from an old people's home." (Michael White, Guardian, 9th May 2010)His mother, a middle-class Welshwoman, had been born in 1893 when it had not been fashionable for her class to speak Welsh, so Watkins was brought up speaking only English in an area where Welsh was overwhelmingly the majority language. His own accent was pure cut-glass, definitely not something learned on the streets of Tycroes or Ammanford, mining communities both.

Although not a journalist in the strict sense of that word—a journalist, from the French jour, day, is someone who writes on a daily basis—he was, more correctly, a political columnist, contributing weekly comment and opinions on topical political matters. In fact, Watkins never worked for a daily newspaper, only Sundays or weekly magazines. In the words of a phrase which he helped to popularise, he was a member of the 'chattering classes', as Brewers Politics defines the term:

Chattering Classes: A UK, and specifically London, term for the intermeshing community of left-of-centre and middle-class intellectuals, especially writers, dramatists and political pundits, who believe their views should carry enormous weight and have considerable access to the BBC and much of the media. Originally this term was coined in the first years of Margaret Thatcher's ascendancy to disparage the liberal intelligentsia who raged impotently about Thatcherism around the dinner tables of North London. It was popularised by Alan Watkins, the Observer's political correspondent, who widened its meaning to include people of all complexities united only by their chattering.

(Nicholas Comfort, Brewer's Politics (1993, revised edition 1995), page 88 and quoted by Watkins himself in his memoirs A Short Walk Down Fleet Street, published in 2000).

As well as 'chattering classes'; the phrases 'men in suits' and 'young fogies' are often attributed to Watkins but he was not the creator of any of them, merely helping to popularise them.

In over fifty years of journalism, Alan Watkins had written his political columns as 'Crossbencher' for the Sunday Express (1959-64); the Spectator (1964-67); the New Statesman (1967-76); the Sunday Mirror; the Observer (1976-93); and, most recently, the Independent on Sunday. In 1993 the Observer was taken over by the Guardian which led to a row over pay and his departure (the Guardian had the temerity to suggest Watkins should take a pay cut). He has also written a general column for the London Evening Standard, a drink column for the Observer magazine and a rugby column for the Independent, columns he wrote until just before his death on 8th May 2010.

Despite having been briefly a Labour councillor in Fulham (1959-62), Watkins was recruited as their political correspondent by the Tory-supporting Spectator shortly after the Tories lost office in 1964. While a Labour councillor at Fulham Watkins was credited with a decision to ban old people from huddling in public libraries. He argued that libraries should be places of learning, not simply places where pensioners could keep warm, so perhaps he felt the right wing Spectator was somewhere he too could huddle with like-minded folk.

In 1967 he shuffled leftwards again when he moved to the New Statesman, then edited by Paul Johnson, where he remained until 1976, first under the editorship of Richard Crossman, an ex-Labour cabinet grandee, and later that of Watkins's brother-in-law, Anthony Howard. Watkins had married young ("I was virtually a child bridegroom") to Ruth Howard, sister of his future New Statesman editor, Anthony Howard. At the request of Richard Crossman in 1971 Watkins abandoned his staff status to go freelance and he remained a freelance for the rest of his journalistic career, freeing him to write columns for several publications at the same time.

He could be controversial and anti-authority, as his obituarist Michael White writes in the Guardian newspaper:

"It was while at the Spectator that Watkins had his first serious brush with authority when, in 1967, he published two D (for defence) Notices in his column—hitherto secret documents warning newspapers what they could (not) print on security grounds. There was a row and an inquiry under Lord Radcliffe.

..... The Spectator was condemned, but Watkins was unrepentant. Among later controversies, his most alarming was the costly three-week high court libel action brought against Watkins and the Observer in 1988 by the Labour MP Michael Meacher, whom the columnist had accused of embellishing his working-class credentials. Meacher lost and Watkins, who had spent three days in the witness box, wrote a book: A Slight Case of Libel (1990)." (Michael White, Guardian 9th May 2010.)Apart from his weekly columns on politics, wine and rugby, Watkins also produced eight books, notably Brief Lives (1982), an attempt to capture his Fleet Street and Westminster contemporaries in the style of the 17th century diarist John Aubrey; A Slight Case of Libel (1990), which wittily described his successful defence of a libel action brought against the Observer by the Labour MP Michael Meacher; and A Conservative Coup (1991), a well-informed and engrossing account of the fall of Margaret Thatcher.

His proprietors have included Lord Beaverbrook (whom he used to accompany on walks around New York's Central Park), Ian Gilmour, 'Tiny' Rowland and Tony O'Reilly; his editors, John Junor, lain Macleod, Nigel Lawson, R.H.S. Crossman, Conor Cruise O'Brien, Rosie Boycott and Janet Street-Porter. He has known most Prime Ministers from Harold Macmillan to Gordon Brown.

It's interesting to note that Watkins could move from the right wing, pro-Conservative Spectator to the leftish, Labour-supporting New Statesman without having to change the political slant of his columns. He also fitted in, without any seeming effort, to the Labourite Sunday Mirror even though he had started his journalistic career in the decidedly Tory Sunday Express. More an insight into how indistinguishable from each other British newspapers really are, whatever political parties they purport to champion, this also indicates how some journalists prefer to exhibit flexibility above whatever other talents their maker has seen fit to bestow on them. But then Alan Watkins is perfectly capable of speaking for himself on his political allegiances:

"As I grew older I came to realise that I got on better with people who were considered to be on the right politically ... than with those who were thought of as representatives of liberal enlightenment." (A Short Walk Down Fleet Street, 2000, page 194)

His Daily Telegraph obituary paints an amusing picture of our now-legendary Fleet Street scribe in his later years:

Towards the end of the week he could, by this stage, sometimes be found in a heap of sleep at his desk. Visitors would pause at his office door and be shown a figure snoring like a walrus. "That," a guide would whisper, "is Mr Alan Watkins composing his Sunday column." (Daily Telegraph, 9th May 2010.)

He enjoyed a glass of champagne ("a little of the sparkling wine of north-east France, if I may" he would say at the bar), but he also enjoyed a good claret and Armagnac. Watkins had a habit of avoiding the press galleries in the Palace of Westminster and preferred to meet friends, MPs and colleagues in near-by bars. A particular favourite was the legendary Annie's Bar at the House of Commons, restricted to Members of Parliament and journalists, and where off-the-record information could flow once tongues had been loosened sufficiently by drink. But with the advent of digital television came the broadcasting of parliament and Watkins in his later years would follow parliamentary debates from home without having to make the trek to parliament too often.

Not that he allowed the digital world to intrude upon his well-ordered life. Until very recently he wrote his columns in long-hand, in black ink on lined foolscap paper, and dictated them by telephone to his newspaper. Such was his reputation that he was the only journalist in today's highly technological media industry who was allowed to get away with this by-now obsolete way of writing. When his daughter bought him a laptop computer he never used it.

Another favourite watering hole which became synonymous with Fleet Street was El Vino's wine bar:

The offices of the New Statesman were handily sited for El Vino, a dusty wine bar at the junction of Fleet Street and Fetter Lane to which, at dusk and often earlier, a bookish crowd of journalists would proceed like elephants to a Serengeti watering hole. Watkins, along with such men as Peregrine Worsthorne, Paul Johnson and Peter McKay, was to be found there most evenings. (Daily Telegraph obituary, 9th May 2010)

Yet another of his frequent hang-outs was the historic Garrick Club in Covent Garden, founded in 1831. Like all private clubs of the time it was founded for 'gentlemen' only, and still excludes women from its membership today. Women may be invited as guests of a member (though the cocktail lounge is out of bounds to them), but have no voting rights. Founded to promote theatre in London and as a place where members of the theatrical world could meet like-minded people (its motto is "All the world's a stage"), today's membership has expanded to include a large sprinkling of musical, artistic, literary, media, political, military, legal and professional types amongst its many famous actors (but not actresses). Dukes, Viscounts, Earls, Marquesses and Barons are found in abundance on the membership list, and Baronets and Knights are just as plentiful. The Garrick Club is not easy to become a member of. The waiting list stands currently at seven years and new candidates cannot apply for membership themselves but must be proposed by an existing member before an election in a secret ballot of the committee, and 'blackballing', or refusal of membership, is not unknown. The Garrick Club boasts the largest collection of theatrical paintings and drawings in the world and one of the largest collection of establishment figures in the country. In 2010 its annual membership fee is in the region of £1,500.

Watkins was the model for Private Eye's Alan Watneys, named after the now-extinct brewery chain, Watneys. Though this clearly hints at Watkins' renowned fondness for drink, his preferred tipples were the far more sophisticated champagne and claret, so this reference to a brewery whose products were notoriously undrinkable seems deliberately designed to enrage him.

As already mentioned, in 2000 he published his journalistic memoirs of those forty years entitled A Short Walk Down Fleet Street (Duckworth). The opening chapter relates some affectionate memories of his father – D J Watkins (1894–1980) from Tycroes who had been a headmaster at nearby Llanedi Primary School, and his mother Violet Harries (1893–1986) from Gorslas who had been a school teacher in Blaenau, near Llandybie. From his mother came his love for correct grammar and syntax in his prose style. For reasons that are still unclear, D J Watkins had been dismissed as headmaster and afterwards taught as an ordinary teacher in Parcyrhun Primary School, Ammanford. According to Alan Watkins:

"There was an adverse inspector's report. In the year of my birth, 1933, he was deprived of his headmastership and given the choice of becoming headmaster of another small school in Pembrokeshire or joining the staff of Parcyrhun School in Ammanford as an ordinary teacher. He chose the latter and remained embittered for the rest of his life, often falling into rages, though these became less frequent as he grew older." (A Short Walk Down Fleet Street, page 12).

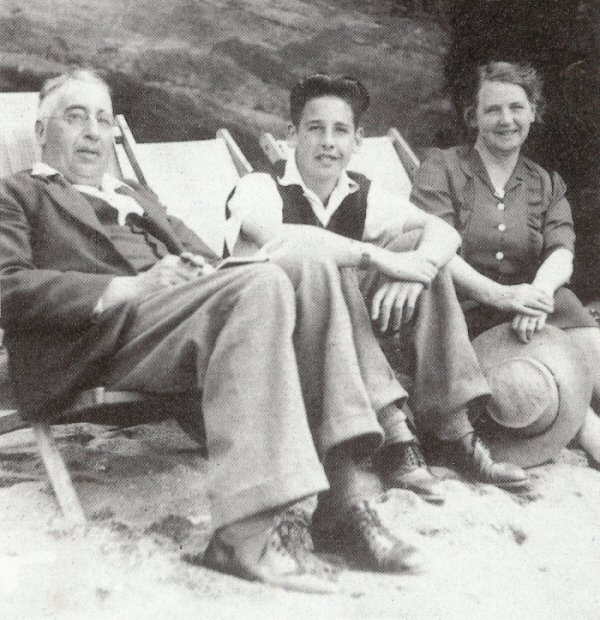

Alan Watkins, aged 15, with his parents on a family holiday in Ilfracombe in 1948

Of his own early years, blink and you'll miss them completely, so little space is devoted to them in his memoir. His seven years at Amman Valley Grammar School (where he was head boy) are omitted completely and his Cambridge years receive the briefest of mentions. Instead he concentrates, to the exclusion of almost everything else, including family and personal matters, on the life of a Fleet Street journalist from that legendary thoroughfare, not missing out its numerous watering holes en route. Given the somewhat caustic views he's expressed on his home town, it's perhaps not surprising he leaves Ammanford out almost completely from his memoirs. Most recently in a BBC Radio Wales programme, a sort of Welsh Desert Island Discs, he poured scorn on the village of his birth and its residents. He couldn't stand the Amman Valley Grammar School because it was too Welsh, he said, though the nickname his fellow pupils gave him—Ffwnga (the Welsh for Fungus)—might possibly explain this animosity to his old school.

Watkins can, though, be a bit more forthcoming about his home town in his weekly journalism and his remarks in the Sunday press on the valley of his birth have always been negative: once he defined a bout of depression as "a wet Sunday afternoon in a place called Ammanford".

In another Independent on Sunday article, ostensibly about Ammanford-educated Neil Hamilton and his formidable wife Christine, he took the opportunity of making this side-swipe at Ammanford in passing:

Mrs Hamilton was quoted on a previous occasion as saying that her function was to inject some vim, zip, drive and initiative into her husband, who would otherwise have been a perpetual student. And indeed – to indulge in some generalising of my own – there is a tendency for people from Mr Hamilton's part of the world [ie Ammanford] to put things off, to find excuses for inaction. A favourite formulation is: "I'll do it fory," fory being a contraction of yfory, or "tomorrow", further defined as "like mañana, but without the same sense of urgency". (Alan Watkins, Independent on Sunday, 19th August 2001 – see below for the article).

Not one to miss a chance to sneer at his home town, our Mr Watkins or, as he puts it, "to indulge in some generalising of my own". Bless him.

Whatever its intended audience, A Short Walk Down Fleet Street seems to have been written for the exclusive readership of Fleet Street habitués, consisting of little more than a long and, to the outsider at least, often tedious retelling of Fleet Street gossip, leavened only by relentless name-dropping of the countless journalists and politicians who criss-cross its pages.

A book for the insider then, A Short Walk Down Fleet Street draws upon a lifetime's experience in politics and journalism. In its pages the likes of Harold Wilson, Lord Beaverbrook, 'Tiny' Rowlands, Anthony Crosland, Tom Driberg, Barbara Castle, Hugh Cudlipp and Malcolm Muggeridge rub shoulders with lesser mortals. If the book has a hero (only Watkins, perhaps, would see himself as the hero), it is Old Fleet Street itself which, along with its somewhat louche and occasionally criminal denizens, lasted until the 1980s but is now, as Watkins puts it, as remote as the Byzantine Empire. The name Wapping, where most newspapers now reside, doesn't have quite the same resonance as Fleet Street. His book, however, gives a possible explanation as to why only elderly journalists from that era might bemoan its passing. Even Watkins himself seemed aware of the danger of this, as he begins A Short Walk Down Fleet Street with the following quote from fellow journalist Ian Hargreaves: "You have to marvel that anyone still wants to publish loving accounts of Fleet Street's alcoholic triumphs and expenses fiddles." (Independent, October 16, 1999.)

On his private life, which Watkins was so reticent about in his memoir, his obituarist in the Guardian newspaper was more forthcomin after his death:

"Watkins's private life was marred by misfortune. Before he and his wife Ruth separated in 1974, she had attempted to kill herself. In 1982, she succeeded and the following year their daughter Rachel, who had found her mother, did the same. As in much else, Watkins remained adamantly libertarian on the individual's right to commit suicide." (Guardian, 9th May 2010)

Increasingly oppressed by failing kidneys, he struggled unsuccessfully with dialysis and took to his bed in April 2010. On Saturday May 8th 2010, his son David was about to read him the election sketch of a fellow columnist when he noticed his father had slipped away.

His final column described the first-ever television debate between party leaders in the 2010 UK general election:

"Mr Clegg [the leader of the Liberal Democrats] is adept at the soft answer that turneth away wrath. He does not have anything to teach Mr Cameron [leader of the Conservative Party]; still less poor Mr Brown [Prime Minister and leader of the Labour Party], who chews gum even when he does not have anything to chew." (Independent on Sunday, 18 April 2010.)

Those, his last published sentences, give a good flavour of his journalistic style. Of the controversial Conservative, Edward du Cann, he wrote: "Talking to Edward du Cann was rather like walking downstairs and somehow missing the last step. You were uninjured but remained disconcerted."

The authors who most influenced him were P G Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh and he modelled his writing on these two renowned stylists, their perceived lack of depth not being considered any obstacle to his journalism. Of course, a concentration on style at the expense of content can lead to the substance being squeezed out of your writing, something he could sometimes be accused of. One of his former editors even wrote of Watkins that no journalist had given him greater pleasure, though others may have given him more intellectual stimulation (see Peter Wilby, below).

By his death, Watkins was universally regarded as one of the last of the old school of Fleet Street journalists, someone for whom an elegant prose style, an appreciation of fine wines, and a mastery of filling in expenses forms were essential tools of the journalist's trade. He took full advantage of the opportunities that era afforded him, revelling in what he called "the Silver Age of Fleet Street", an admission that its Golden Age, whenever that had been, was not during his time. He was, finally, one of those people whom few could praise without some qualification creeping in with the same breath, as his Guardian obituarist tellingly shows:

He was distinguished as an erudite pundit, a writer of stylish prose and a lively phrasemaker. These qualities, combined with a bloody-minded streak of independence, ensured a professional longevity rare in his ephemeral trade, especially among those who drank seriously. Watkins did. (Michael White, Guardian, 9 May 2010.)

In similar vein his Daily Telegraph obituarist describes him as "paunched and bottle-worn", but then soon adds: "Despite a façade of frayed indolence he was, from the mid-1960s to the 1980s, one of the Westminster lobby's better-informed journalists and shrewdest commentators." Again, "In dress and hygiene he exuded mouldiness but in wit he was agile." (Daily Telegraph, 9 May 2010).

Watkins' journalistic career seems to have been not entirely free from either controversy or enemies, as this review of his memoir by a former colleague indicates:

Peter Wilby

Why I fell out with the prince of columnists

A review of A Short Walk Down Fleet Street, by Alan Watkins.

British Journalism Review

Vol. 11, No. 4, 2000, pages 63-66There are many good things in the Sunday newspapers (which is not the same thing as saying that they are good newspapers) but there is only one thing to which I unfailingly turn: Alan Watkins's column in the Independent on Sunday. I do so, not because it adds to my stock of knowledge (though it sometimes does), but because of the writer's unrivalled ear for the cadences of English prose, his wit and mischief and, above all, his refusal to take politicians as seriously as they take themselves ...

....So why, when I was charged with shepherding Watkins into print at the Independent on Sunday from 1993 to 1996 – first as Deputy Editor, then as Editor – did we fail so badly to hit it off? I spent much of those three years in a state of disgruntlement and disillusion with Watkins. Indeed, I toyed occasionally with the idea of dispensing with his services entirely and once even checked his contract to see how much notice was required. I had not realised the extent to which Watkins reciprocated these feelings until I consulted the index to this book.

.... There I found references to "Wilby, Peter, Alan Watkins' relations with" stretching over five pages, thus giving me the same degree of attention as the better-known and more substantial figures of Crossman, R. H. S. and Cole, John, both of whom had enjoyed equally troubled relations with A. W. as respectively editor of the New Statesman and Deputy Editor of The Observer. Watkins, I should make it clear, pays me several compliments in this memoir of his career in journalism. He supported my candidacy for the Independent On Sunday editorship and our social relations remain cordial, though not intimate, to this day. We have had arguments, but never rows. (Watkins is very particular about the distinction). Nevertheless, he makes it plain that over our three years as colleagues, I consistently niggled him: about his pronouns, about his language (I once decreed that he could not describe an African dictator as "a dusky despot"), about his subject-matter, about his general approach to politics.

.... The reasons for this unhappy episode may be thought to lie in the personalities of the two protagonists and therefore to be of little interest to anybody else. No doubt that is largely true. But they also, I think, say some things of wider importance about the relationships between editors and star columnists. I have discovered that it is not unusual for editors to be vaguely disgruntled with and uneasy about a columnist that everyone else admires. The first point is that star columnists are expensive. When I was there, Watkins's freelance contract costs the Independent on Sunday £60,000 a year and for this he was required to write one column of about 1,200 words, 46 weeks a year. I know that, against what some big names command, this was a mere snip.

.... Nevertheless, the Independent On Sunday was and is a cash-starved paper. It operates essentially as a bodiless head since, while it has a full complement of editors for home and foreign news, arts, books and so on, it is expected to draw its writers largely from the daily paper's staff. For Watkins's money, I could have easily doubled my full-time reporting staff. Moreover, Watkins also expected us to pay his expenses which involved daily journeys by taxi. These latter were recorded in algebraic form – N1-SW1; WC2-EC4; SW1-EC1; WC2-N1, and so on – and, I quickly realised, represented Watkins's daily peregrinations between his home in Islington, the House of Commons, the Garrick Club, the New El Vino's at Blackfriars and the Independent On Sunday offices, then in City Road. I took particular exception to N1-SW1 and N1-EC1 since, as I pointed out to Watkins, it was unusual for employers to reimburse journalists for what, in effect, were their journeys to work, and even more unusual for such journeys to be taken by taxi. To be fair, he agreed to moderate his expenses but they remained substantial.Disappointment

A second point about star columnists is that they nearly always disappoint. Editors like to imagine that a new columnist will bring, in his or her wake, a loyal following of readers. They believe, with equal conviction, that they will suffer catastrophic circulation losses if a star columnist moves to a rival. This is why some columnists command such astronomical fees. Yet there is not the smallest evidence, beyond the anecdotal, that a columnist's move has any effect whatever. Journalists notice each other's names far more than the readers do. Readers often, it is true, lament the departure of a columnist, but they rarely take the trouble to find out where he or she has gone to. Thus, when Watkins joined the Independent On Sunday from The Observer, the two papers' circulations had been converging so rapidly that it seemed possible for the former to overtake the latter within two years. We thought Watkins's acquisition would be the decisive blow. In fact, and I do not suggest there was any connection, circulation fell steadily from the day he joined.

.... The third point about editors and star columnists is, I think, the most important. Editors want to ... well, edit. This is not a matter, as Watkins seems to think, of their wishing to re-write copy to their own preconceptions. Rather, their role has been well compared to that of orchestral conductors: a little more brass here; a touch more wind there; now a slower tempo; now a faster one. They do not want to seize the instrument off the lead violinist; but they would rather the violinist didn't play from an entirely different score. The best columnists, however, have their own agenda. They are idiosyncratic, egotistic, unpredictable. That is what makes them good columnists. They prefer to write about their own passions of the day or week, not their Editor's. The Editor may be anxious that such-and-such a subject be covered on the comment pages, and think the columnist the obvious person to do it, only to find the columnist has quite different ideas.

.... This was the nub of my difficulty with Watkins and, I learn from this book, also of Crossman's. As Watkins correctly notes, I became irritated with him because I thought he "had chosen the wrong subject for the week, or had gone about it in the wrong way." Watkins always rang me on Thursdays to tell me his proposed subject in order, as he put it, to prevent "overlap." It soon became clear to me that this exercise was to stop other people overlapping with Watkins, not vice versa. Moreover, Watkins, while anxious to avoid duplication, had no interest in helping to avoid omission: he was not susceptible to suggestions that he should cover a subject – a new Tory row over Europe, say – because the readers would expect some comment on it and we had no space for it elsewhere. (His biggest row with Crossman was in 1970 over Watkins's failure to make adequate comment in his column on a Tory reshuffle). Still less was he interested in suggestions about what readers would want to know. The result often seemed to me quite exasperatingly perverse. For example, during Tory leadership crises (and they came along about once a month during those years), Watkins would insist on devoting most of his column to a tedious (in my view) repetition of the precise rules for removing a Tory leader and electing a new one.

.... I repeat: no journalist has given me greater pleasure than Alan Watkins, though others may have given me more intellectual stimulation ... It might have been better if each of us had had some experience of the other's role. But so far as I know, Watkins has never aspired to an executive role on a newspaper ... columnists rarely become editors and, when they do they are often judged unsuccessful. (Ex-editors often become columnists, but not brilliantly). Perhaps they must always suffer from mutual incomprehension.Peter Wilby, 2000

Alan Watkins on Neil Hamilton

Another former pupil of the Amman Valley Grammar School who ventured out into the wider world beyond our little valley is the discredited former Tory Minister Neil Hamilton, currently pursuing a media 'career' with his wife Christine (see the Note below). It's always interesting to learn what one Ammanfordian thinks of another, so here is Tycroes-born Watkins, in his Independent on Sunday column of 19th August 2000, on Neil and Christine Hamilton:The second most famous former pupil of my old school is Mr Neil Hamilton. The most famous is or, at any rate, used to be Donald ("By a babbling brook") Peers, the Tom Jones of his day [see Note 1 below]. On the whole, however, we are a self-effacing lot, numbering among ourselves at least one other MP who, like Mr Hamilton, departed the House in sad but less spectacular circumstances, Dr Roger Thomas; several notable rugby players; numerous learned professors; an abundance of college lecturers; and countless schoolteachers.

.... I mention this because, in all the reams of paper that have been devoted to Mr Hamilton and his wife, hardly anyone has thought it worth mentioning that he was brought up in Ammanford, Carmarthenshire, where he attended the local grammar school. From there he went on to the University of Wales at Aberystwyth (Economics) and thence to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (Law).

.... This could not have been an easy progress 30-odd years ago, even for someone whose father was as prosperous and well established as Mr Hamilton's. He was not a native of the area but had migrated from Monmouthshire to assume the post of chief engineer for the coal board, a position previously held by Lord Richard's father [Lord Richard of Ammanford, ie Ivor Richard—see Note 1 below]. There are six near-contemporary politicians who were all brought up within a short, narrow coastal strip of South-west Wales, from Carmarthen in the west to Aberavon in the east: Denzil Davies, Neil Hamilton, Michael Heseltine, Michael Howard, Geoffrey Howe and Ivor Richard. And they all speak differently. True, Mr Heseltine, Lord Howe and Lord Richard were sent away to school. But that cannot account for the variations in the speech of the other three. It goes to show that Welsh people cannot be stereotyped as they tend to be, perhaps to a greater extent than natives of other countries are.

.... Mr Hamilton was called to the Bar at the comparatively advanced age of 30. He was four years older when he married Christine Holman, a Commons secretary. This happened during the election campaign of 1983, when Mr Hamilton won Tatton. They had first met in student politics, and married after an interrupted courtship. Mrs Hamilton was quoted on a previous occasion as saying that her function was to inject some vim, zip, drive and initiative into her husband, who would otherwise have been a perpetual student. And indeed—to indulge in some generalising of my own—there is a tendency for people from Mr Hamilton's part of the world to put things off, to find excuses for inaction. A favourite formulation is: "I'll do it fory," fory being a contraction of yfory, or "tomorrow", further defined as "like mañana, but without the same sense of urgency". (Alan Watkins, Independent on Sunday, 19th August 2001).Note:

Brief biographies of Neil Hamilton, Donald Peers and Ivor Richard who are mentioned above can be found in the 'People' section of this web site.In addition to A Short Walk Down Fleet Street Watkins has written a total of eight books, all political works drawn from his journalistic career.

Sources: Watkins's own memoir, A Short Walk Down Fleet Street (Duckworth, 2000), and obituaries in the Times, Guardian, Independent, Observer, Scotsman and Telegraph, on 8-9 May, 2010. Click HERE for the full text of some of these obituaries. Click HERE for the first chapter of Watkins autobiograpy dealing with his Ammanford years.