AN ABERLASH MILLIONAIRE

THE RAGS TO RICHES LIFE

OF DAVID DAVIES, ABERLASH1.....Aberlash

2.....Ystalyfera's Philanthropist — the rags to riches life of David Davies

3.....A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in CarmarthenshireThe river Loughor in Carmarthenshire is hardly one of the great waterways of the world. From its origins in an underground lake beneath the Black Mountain, it rushes into the upper world through a fissure in a rock called Llygad Llwchwr (the eye of the Loughor). But within fifteen miles of its source, the salt waters north of the Gower peninsula soon swallow up its early promise, though not before it plunges thirty feet over a rock at Glynhir near Llandybie to become the highest waterfall in Carmarthenshire. The name Llwchwr, which is the original Welsh name for the river, comes from 'llwch' = lake, and 'dwr' = water; hence 'lake water', a constant reminder of its origins.

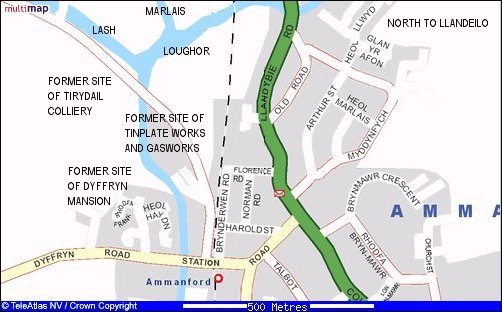

The main tributary of the Loughor is the river Amman just a mile downstream from Ammanford, which thus signals the end of the Amman Valley (the Amman doesn't have so picturesque a birth as the Loughor, oozing imperceptibly instead from a bog on the Black Mountain above Brynamman). Two other tributaries of the Loughor, just a couple of miles upstream from the Amman–Loughor confluence, are the rivers Marlais and Lash. The name Marlais, deriving from 'marw' = dead and 'glais' = stream or water, means 'dead water', as the river traces a rather sluggish course through Llandybie until it reaches the Loughor at Aberlash. Only a few yards downstream is another river, the Lash, probably a corruption of the Welsh 'lais', a stream, and these two little rivers form a double confluence with the Loughor at this point.

The place at which the Lash mingles its waters with the Loughor is known as Aberlash — the mouth of the Lash — giving its name to the general area where the three rivers meet, and it is here that our current story begins. The tranquil setting of today's Aberlash, with just a few houses clustered around some small farms, disguises a more turbulent past, because this was once a scene of major industrialisation. A hundred years ago, the clamour of a tinplate works, a colliery, a textile mill, a gas works, the rumbling of coal trucks along a nearby railway line, and the clanging and banging of shunting from the rail sidings would have rent the air with harsher sounds than can be heard today. Now, all is quiet (except for the inevitable cars purring by); Tirydail Colliery, sunk in 1895, closed in the aftermath of the 1926 General Strike, by when other mines dotted along the banks of the Lash had already closed; Aberlash Tinplate Works, opened in 1889, was dismantled in 1912 after ceasing production in 1908; the gasworks closed sometime in the 1960s; and the woollen mill that stood at the mouth of the Lash (and once gave the name of Weaverstown to a nearby cluster of mill-workers' cottages) has long been converted into a private residence. These industrial buildings are now all gone, the mineral railway line torn up in the 1970s after being abandoned in the 1950s, and even most of the farms have ceased or reduced their farming activities, content to sell off land for property development rather then farm it.

One of the farms which is still operating from those days is Aberlash Farm, and a boy named David Davies, born in 1854 to an impoverished farm labourer there, would one day make his fortune amongst similar collieries and tinplate works of the industrial revolution. (The Welsh word for a farm labourer is 'gwâs', meaning literally 'servant', showing clearly the lowly status of such employment.) It was to be in the nearby Swansea Valley however, rather than his native Aberlash, that the opportunities would present themselves in adult life to this child who, at his death in 1837, would leave £24 million in his will as irrefutable proof of his success. Others instead would be the ones to exploit the opportunities available at Aberlash.

Lieutenant-Colonel William Nathaniel Jones, one of the founders of modern Ammanford, was one of the new breed of industrialists who were swiftly replacing the landed gentry in economic and political importance throughout the rural areas of Britain. Their wealth — and therefore power — came not from land and rent income but from manufacturing. Colonel W. N. Jones was one of several of Ammanford's grandees who made their name and fortune by developing industry in the area. He was a prominent local auctioneer and businessman and was briefly the Liberal MP for Carmarthenshire in 1928.

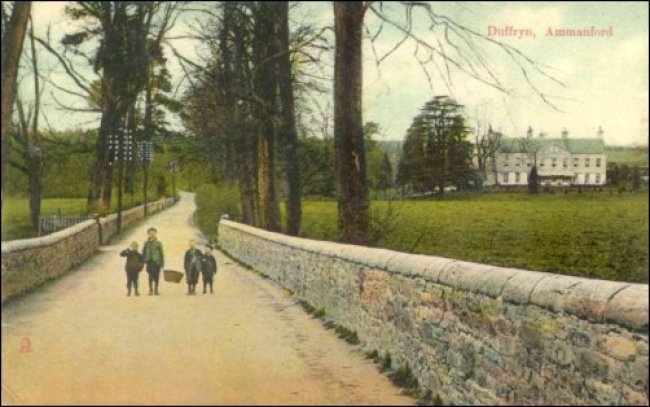

In 1882 the Dyffryn Estate in Tirydail, near the railway station, was placed on the market at auction in ten lots and Colonel Jones bought lots 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8 on the east bank of the river Loughor, though not initially the mansion on the west bank that went with the land. The estate and its mansion dated back to the early 1700s and is believed to have belonged to the Powell family. In 1805, however, the estate passed to a family called Lewes who also owned large estates at Llanllyr and Llysnewydd in Carmarthenshire. William Lewes (1746-1828) of Llysnewydd and Llanllyr inherited the Dyffryn estate after 1805 from his relative William Jones. On the death of William Lewes in 1828 the Llysnewydd and Llanllyr estates were split up between two of his sons, while the fortunes of the Dyffryn branch of the family must have declined considerably for the estate to be broken up and sold to Colonel W N Jones in 1882. [Carmarthenshire Archives Service]

Colonel Jones used the newly acquired land for heavy industrial development. He expanded his operations to build the Aberlash Tinplate Works on the Tirydail bank of the Loughor in 1889, along with Ammanford Gasworks. On the opposite bank of the Loughor he built Tirydail Colliery in 1895. This heavy industry (and, one would guess, dirty and noisy industry as well), caused friction between Colonel Jones and the owners of the nearby Dyffryn Mansion, and a lengthy legal battle ensued. In settlement of the dispute Tirydail Tinplate Company bought out the owner of Dyffryn Mansion, with Colonel Jones himself taking up residence there in 1892. A story about his acquisition of Dyffryn Mansion has travelled down the years which, if true, is quite revealing. According to this tale, production at his Tinplate works (built well within hearing-distance of Dyffryn Mansion, as the aerial photo below will confirm) was increased to 24 hours a day. The noise throughout the night may be easily imagined, but when Colonel Jones moved into the mansion himself in 1892, the former owners having been driven off, night-time production ceased immediately. All good stories deserve to be true, of course, and if this one is correct then today's property developers have no new tricks up their sleeves. Dyffryn Mansion itself was demolished in 1977 after having been abandoned by the descendants of Colonel Jones, and a council-built housing estate called Gwynfryn replaced it in 1980.

Colonel Jones also bought other land around the area for housing to be built for the workforce of the tinplate works and Tirydail colliery, just a few yards across the Loughor from the tinplate works. Three of the streets – Harold Street, Norman Road and Florence Road – bear the names of his children, presumably to gain for his family what the rich think is immortality (and the poor know is vanity).

Arial view of Tirydail/Aberlash taken 24/6/1964 with much of the nineteenth century history still intact. The two cylindrical gasholders of Ammanford Gasworks can be seen just to the right of centre, with the long building of former Tirydail Tinplate works just to their right. Dyffryn Mansion can be seen just across the river, top left. The horizontal line of trees in the centre marks the river Loughor flowing right to left. The houses built for Colonel Jones's workers are at the bottom right. For the nostalgic, the Regal Ballroom is the long building at the bottom left. Tirydail Colliery and Aberlash are at the top right hand corner of the photo. William Nathaniel Jones had a considerable impact on the industrial development of Ammanford but for now the story of David Davies Aberlash, future millionaire of the Swansea Valley, will be the one to occupy our idle moments.

So what took this six-year-old boy's father, William Davies, from the Amman to the Swansea Valley in 1860? Poverty was the immediate reason, obviously, but were there no similar opportunities available in the Amman Valley? Those who grew up in the Amman Valley in the twentieth century associate the area with coal, and coal dominated the economy for over a hundred years, while the ghostly remains of abandoned factories showed us there was once a thriving tinplate industry here as well. The Swansea Valley, then as now, was very similar to the Amman Valley. Both were rural, Welsh speaking communities where large reserves of coal, crucial to the development of the industrial revolution, had been discovered. But the difference was that the Swansea Valley industrialised earlier than the Amman Valley, and it also had deposits of iron ore, so that during February 1837, at the Ynyscedwyn Iron Works, Ystalyfera, the process by which anthracite could be used for the smelting of iron was successfully applied. The credit for this revolutionary step at Ynyscedwyn goes to two people, Mr. George Crane and Mr David Thomas. The latter was to become the leading figure in the development of the coal and iron industry in Pennsylvania, USA. Coal was, and still is, found all over Britain (though you'll search long and hard to find many coal mines any more; as 2008 comes to a close, just five major deep mine are left in the whole of Britain). The crucial difference, however, was that the coal of west Wales is anthracite, which burns at a higher temperature than other grades of coal, and has more uses than just as fuel.

The blast furnaces of the nation's ironworks, the boilers of its steam ships and steam engines, the coking plants that produced town gas, all needed coal for fuel, and the soft steam coal of the eastern valleys was good enough for most of these uses, and good enough for the hearth as well. But anthracite differs in one major respect from steam coal: it is almost pure carbon. Steam coal can have a carbon content as low as fifty percent, whereas the anthracite coal of our western valleys can contain as much as 98 percent carbon. Not for nothing has it been described as black diamond, though only by the coal owners; their employees knew better the words pneumoconiosis and silicosis, horrific lung diseases associated with anthracite mining.

There are five valleys in west Wales where this black diamond can be found, making it the largest anthracite coalfield in Europe. The Amman, Swansea, Dulais, Neath and Gwendraeth valleys all have this coal in abundance, and it is no surprise that the process for using anthracite to smelt iron ore was first applied in one of these valleys.

If William Davies and his family had been born a generation later, they wouldn't have needed to pull up their roots and migrate to Godre'rgraig, near the town of Pontardawe, because by then the Amman Valley, too, had developed collieries and tinplate works of its own. Over a hundred collieries would be sunk during this period of the valley's industrialisation, fueling tinplate works at Pantyffynnon (opened 1880), Glanamman (opened 1881), Garnant (opened 1882), Tirydail (opened 1889) and Brynamman (opened 1890). Aberlash by then would have looked much like Pontardawe or Ystalyfera had done a generation earlier.

The fortunes of some of these Amman Valley tinplate works are as follows: Raven Sheet and Galvanizing Works, Glanaman: opened February 1881; purchased by Grovesend Steel and Tinplate Co Ltd 1913. Amman Tinplate Works, Garnant: opened June 1881; purchased by Grovesend Steel and Tinplate Co Ltd March 1914. Glynbeudy Tinplate Co (1919) Ltd., Brynaman: opened March 1890; purchased by William Gilbertson 1927. (This information was gleaned from E. H. Brooke's Monograph on the Tinplate Works in Great Britain). The last tinplate works in the Amman Valley, the Dynevor Works in Pantyfynnon, opened in 1880 and closed in May 1943, its buildings being finally demolished in the 1970s. All the others had ceased production before this.

The 1861 Census was taken just a year after William Davies and his family set off on their great adventure, and it shows the population of the Amman Valley and District (which includes Llandybie and Aberlash) as being just 4,395 that year. By the time of Aberlash's high point before the first world war, the 1911 census shows a population explosion had taken place in those fifty years, which had risen to 18,584 souls — over 400 percent growth — and the population of Ammanford alone doubled from 3,050 to 6,074 between the censuses of 1901 and 1911. But in 1860 when William Davies took his young family up the Amman Valley and across to Pontardawe, all this was still in the future, so that it was the Swansea, not the Amman Valley that was beckoning families to seek their fortune. This fateful decision would eventually prove to be the making of his son who, while he was growing up in alien surroundings, would be known as Davies Aberlash for the rest of his long life (he died in 1937 aged 83).

It's now about time to move on to David Davies himself, and describe the rags-to-riches life he led after leaving the banks of the river Lash for the last time. We have no record of his emotions as the family left with what few possessions they owned; the knowledge that they were leaving a life of utter poverty might have held back the tears natural to such a wrench, but the hardship they found ahead of them in the first years of their new life could well have made them question at times their decision to leave Aberlash. Once in his new home in the Swansea valley David Davies was put to work in a local tinplate factory at the age of six years of age on a wage of seven pence for a sixteen hour day. This was the norm for the time, but reformers throughout the 19th century succeeded in steadily increasing the minmum age for child labour. After 1867 no factory or workshop could employ any child under the age of 8, and employees aged between 8 and 13 were to receive at least 10 hours of education per week. But such legislation was not foolproof. Inspectors often found it difficult to discover the exact age of young people employed in factories, and reports showed that factory owners did not always provide the hours set aside by law for education.

It took many years for David Davies to progress from a child labourer in a tinplate works to to the owner of a tinplate works himself (and three coal mines for good measure) but that's what he did. This would be an extraordinary achievment even today, with state-provided schools and universities to help smooth the way, but in the 1860s there were no eduational opportunities at all available to childen from the working class. When primary schools were provided by the state from about 1870 onwards it would have been too late for the infant David Davies. As a historian of Pontardawe, where the Davies family relocated, has remarked:

D. W. Davies had no formal education, but improved his knowledge in chapel, Sunday School, penny readings and eisteddfodau. He learnt Psalms and chapters from the Bible and sometimes recited them in Pantteg Chapel, where he was a senior deacon. He was proud to relate that he won a first prize at an eisteddfod at Tabernacle, Morriston, on the subject “Gwell bys na dwrn i agor drws.” (Better a finger than a fist to open a door.) His culture was based on the Bible. (A History of Pontardawe and District, John Henry Davies, pages 83-84, published in 1967.)

He would never forget his own lack of educational opportunities and in later years he supported education for others by giving scholarships to his employees, and £1,000 towards a scholarship at the Grammar School, Ystalyfera.

A brief article on David Davies, Aberlash, by Julian Leigh Williams is reproduced below. Additional notes at the end are by the author of this website, and are not in the original article. And, as Davies Aberlash was to make his fortune in the iron and coal industries, for those who wish to read further we also provide more detail about these industries in Carmarthenshire, including the Amman Valley.

1.....Aberlash

2.....Ystalyfera's Philanthropist — the rags to riches life of David Davies

3.....A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in Carmarthenshire

2 Ystalyfera's Philanthropist — the rags to riches life of David Davies; by Julian Leigh Williams (See Note 1 below) On 18 April 1854. David Davies was born in a cottage near Aberlash Farm, which was situated near Ammanford in Dyfed.

.....He had been born into a large poverty-stricken family and his father, William Davies, earned a living as a labourer on Aberlash Farm.

..... David Davies, however, was destined to become one of the wealthiest and most influential men in the Swansea Valley by becoming a successful colliery proprietor. The life of David Davies is one that took him from rags to riches.

..... In 1860, William Davies decided to take his wife and their children to live at Pentalwn in Godre'rgraig, near the town of Pontardawe, in the Upper Swansea Valley. William Davies soon found employment in the Ystalyfera Iron and Tinplate Works, which was owned by a local businessman named James Palmer Budd. David Davies, who was then six years old, also went to work in the iron and tinplate Works. At such a young age, he had the grueling experience of having to work sixteen hours a day at a daily wage of 6 pence. As there were several David Davieses working in the ironworks, David adopted his father's name as his second name. Thus, he became known as David William Davies. He also became known by the surname of 'Davies Aherlash' after Aberlash Farm.

..... David William Davies had no schooling, as his life was spent in the iron and tinplate Works, but he improved his knowledge as best he could by attending Chapel and Sunday School.

..... He became a frequent competitor at the Penny-Readings and local eisteddfodau. He also learnt chapters and psalms from the Bible, which he sometimes recited before the congregation at Pantteg Chapel, in Ystalyfera, where he would one day become a senior deacon.

..... Throughout the years of his life, David William Davies was a very religious and God-fearing man and he once said, "The Bible will teach you how to live and how to die".

..... When the ironmaster James Plainer Budd inspected the iron and tinplate Works every Monday morning, he was shown the best tinplates and, after he had gone, the shining tinplates were then stored safely away as, unbeknown to the ironmaster, they were the same tinplates shown to him in his weekly inspections. David William Davies then decided that, if he ever became an employer, he would he wary over such dirty tricks ever being played on him. (See Note 2 below)

..... The early 1880s was a time when the Upper Swansea Valley was hit by a depression as work became scarce. James Palmer Budd died on 9 December 1883 at the age of eighty, and the iron and tinplate works began to deteriorate until it finally closed down in 1886. Many families moved away from the area in search of employment, but David William Davies was to bring prosperity back to Ystalyfera and the neighbouring villages.

..... In 1886 – the year when the Ystalyfera Iron and Tinplate Works closed down – Davies Aberlash decided to reopen the old Pwllbach Colliery in Ystalyfera. The colliery had first been opened by a colliery proprietor named Daniel Harper in 1812, but the colliery had been idle for many years.

..... Many people believed that his venture to reopen this old colliery would end in failure, and it was a very hold and daring venture, as Davies Aberlash had no experience at all in coal mining. A few local friends, however, believed that the reopening of the colliery would he a success.

..... A story goes that the men employed at Pwllbach Colliery by Davies Aberlash found coal in the mine, but the miners soon struck a fault and they lost all trace of coal.

..... Davies Aberlash told his workmen that he had spent all his money and, therefore, he couldn't pay their wages.

..... As the men had no work to go elsewhere, they continued to dig in search of coal for a fortnight and, to the astonishment of many people, a rich vein of coal was discovered beyond the fault.

..... Davies Aberlash paid all his men the wages owing to them, and so Pwllbach Colliery became a great success. It made David William Davies Aberlash a wealthy man and the colliery brought employment to hundreds of men from the area.

..... Davies Aberlash then took Mr. Edmund Cleeves of Swansea into partnership and they formed the Pwllbach Colliery Company with Davies Aberlash as its managing director.

..... The colliery under his supervision provided employment for nearly forty years. And was later handed over to the Amalgamated Collieries Ltd., employing between 600 and 700 men. (See Note 3 below)

..... Encouraged by the success of Pwllbach Colliery, Davies Aberlash took advantage of the experience he had as an employee of James Palmer Budd's Iron and Tinplate Works.

..... He acquired the Phoenix Tinplate Works, in Ystradgynlais and thus he brought more employment into the area.

..... A few years later, he opened two other collieries – The Diamond Drift Colliery in Ystradgynlais, and the Tirbach Colliery in Ystalyfera. (See Note 4 below)

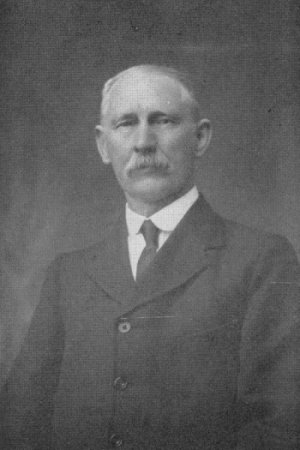

.....David William Davies Aberlash had now become a much respected man in the Upper Swansea Valley. Though he was known as 'Davies Aberlash', he was also known by the surnames of 'Davies Tycoch', after his red-bricked house in Ystalyfera, 'Davies Pwllbach', and 'Davies Tirbach after the collieries which he owned.

.....Though he became a very wealthy man, Davies Aberlash didn't forget his poor and humble beginnings. He became known in the Upper Swansea Valley for being a philanthropist as well as a leading industrialist – he supported education of others in many ways, such as giving scholarships to his employees, and he donated £1,000 to Ystalyfera's Grammar School.

..... His generosity knew no bounds and he often gave donations to clear the debts of many local churches in the area.

..... He took particular interest in Pantteg Church in Ystalyfera and he donated £600 for the rebuilding of a vestry at the Pantteg Church. It was a proud moment in his life when he was elected as a senior deacon at Pantteg Church in 1901.

..... In 1924, now at the age of seventy, Davies Aberlash gradually retired from the coalmining industry which he had re-established in Ystalyfera. He did, however, devote himself to public and social duties during his retirement.

..... In May 1935 he gave a gift of £10,000 to Swansea General Hospital (now Singleton Hospital). The gift was given on condition that a new hospital block would be known as the 'D. W. Davies Block' and it would have a ward named the 'Martha Davies Ward' alter his wife. The gift was a thanks-offering for his wife's recovery from an illness.

..... The money was handed to Dr Clark Begg in a sealed envelope at the opening of the new block. The amount of this generous gift covered the cost of the building materials, and so the new hospital block was opened free of any debt.

..... After giving the gift of £10,000 to the hospital, Davies Aberlash maintained a lively interest in the hospital, which he often visited to meet the doctors arid patients. He also became the president of the hospital's contributory scheme at Ystalyfera, and he often discussed at his home the running of the hospital with hospital officials.

..... One of his last public duties was in the summer of 1937 when he opened the outdoor swimming pool in Ystalyfera which had been built for the people of the village.

..... The life of David William Davies Aberlash came to an end in the early hours of the morning of Friday, 26 November 1937, when he died at his home in Ystalyfera at the age of 83.

..... He left hehind a widow, Martha Davies, but their marriage had remained a childless one.

..... His estate was estimated as being £750,000, and some of the estate, known as the 'Aberlash Fortune', passed to his younger brother William Davies, who was a colliery official with the Amalgamated Collieries Ltd. The funeral of David William Davies Aberlash took place on Wednesday, 1st December 1937, at Pantteg Church, and he was laid to rest in Pantteg graveyard. (See Note 5 below)

..... Many colliery official attended his funeral service to pay their last tribute to David William Davies, Aberlash, the industrialist and philanthropist of Ystalyfera......END OF ARTICLE

Notes 1 The above article was found in Ysradgynlais library entitled: 'Ystalyfera's Philanthropist – Julian Leigh Williams tells of the rags to riches life of David Davies.' Details are not given for the date and source of the publication, so any information would be welcome, and can be e-mailed to: terrynorm@yahoo.co.uk] This article seems to be based mainly on a section on David Davies found in A History of Pontardawe and District, by John Henry Davies, pages 83-84, published in 1967. 2 Davies Aberlash seems to have been a classic case of poacher turned gamekeeper, one who knows all the tricks from the inside, and it would be interesting to find out the working conditions at his own work-places; few have yet grown rich by worrying too much about their employees. 3 The Amalgamated Collieries Ltd. bought out the full share complement at market value, so it wasn't exactly 'handed over'. See Chapter 3 below, 'A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in Carmarthenshire', section 3 'The Anthracite Coal-Mining Industry'. 4 Tirbach would eventually become a training face for new miners after the coal industry was nationalized in 1947.

5 According to Bank of England figures, the pound in 1937 was equivalent to £32.55 today, so David Davies left £24,412,500 at today's prices, not bad for a farm labourer's boy from Aberlash. A table to convert values of the pound from the year 1270 to the present is supplied by the Bank of England, called 'Equivalent Contemporary Values of the Pound: A Historical Series, 1270—2003', Bank of England, Sept 2003. To see a PDF file with these figures, click HERE. 1.....Aberlash

2.....Ystalyfera's Philanthropist — the rags to riches life of David Davies

3.....A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in Carmarthenshire3.....A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in Carmarthenshire

To satisfy the craving for detail normally suffered by historians, the following summary of the tinplate, steel and coal industries of Carmarthenshire has been taken from the website: http://www.genuki.org.uk/big/wal/CMN/Lloyd5.html

Scattered amongst the copious facts and figures will be found material relating to the Amman Valley.

The Tinplate, Steel, and Coal Industries; by L W Evans

These are the three industries that flourished markedly in the county during the second half of the 19th century. But to understand their origins and development, we must return first of all, to the early days of the industrial period, when the ironworks were migrating to the edge of the coalfield and adopting coal for smelting purposes. With this change, many of the smaller inland ironworks went out of production, and there was a marked localisation of new ironworks, both on the anthracite and the 'Llanelly' coalfields.

1. The Iron and Early Tinplate Industry

The ironworks which declined in importance were those at Cwmdwyfran, Cwmbran, Whitland Abbey, and Llandyfan. The ironworks at Kidwelly and Carmarthen had commenced making tinplates with a great measure of success and were the sole representatives of this industry for the first half of the 19th century in Carmarthenshire.

..... Probably the earliest anthracite colliery in the county was that owned by Kymer of Kidwelly, which produced appreciable amounts of this coal in the last two decades of the 18th century. His colliery was just outside Kidwelly at Forest, and he built a canal to convey the coal to Kidwelly quay. From 1800 onwards, experiments were made in the utilisation of anthracite as a fuel in smelting operations, and after 1838 ironworks were established on the anthracite coalfield.

..... In 1800 Alexander Raby of Llanelly had used Llanelly coal from Penyfinglawdd (Llanelly) in his blast furnace, and in 1817, in conjunction with Simons, opened anthracite collieries in the Gwendraeth valley. Raby's experiments with the use of coal for iron-smelting were, however, not a success. Since 1784, when Henry Cort obtained two patents, one for puddling and the other for the rolling of iron, the iron industry had expanded considerably. Another important advance had been the introduction of the steam engine. This invention helped the mining industry, which in turn produced coal for the smelting industries. Before 1800, therefore, there had been going on careful preparations in the way of new processes and inventions, which created a profound change in the iron industry. From 1800 a new era commenced in the history of the manufacture of iron from the more general use made by the iron masters of the double-power engine devised by Watt.

..... The main results of the use of the steam-engine were the greater producing capacity of the furnaces and the expenditure of more capital by the proprietors. In 1817, Raby and Simons erected the first steam-engine in the Gwendraeth valley for raising coal, which was sent down to Llanelly for export, though 'a great deal found favour in the immediate district for domestic use'.

..... The successful use of anthracite coal in the manufacture of pig-iron dates from 1838. About this time Neilson brought out his process of smelting iron by means of the hot-blast, and anthracite coal was admirable for this purpose. In 1839 there were 26 furnaces in operation on the anthracite coalfield producing 65,780 tons of anthracite pig-iron. The position in 1848 is indicated by the following table;

Name of works Owners Gwendraeth T Watney & Co 3 2 Trimsaran E H Thomas 2 0 Brynamman L Llewellyn & Co 2 2 These furnaces produced more than 4,000 tons of anthracite pig-iron per furnace pa. For a number of years this production was well maintained. There are no returns after 1851. In 1859 the Amman ironworks passed into the hands of G B Strick and Co. The first ironworks to be built in the Llanelly area during the period 1800-50 were those at Dafen, about a mile and a half to the north-east of the town. They were built by Messrs Motley and Winkworth in 1846. The works had a number of puddling and ball furnaces (ffwrneisi bach), and a mechanical hammer for beating the bars into plates. In 1856, Messrs Phillips, Smith & Co acquired the works, and in 1869 the firm was known as Phillips, Nunes & C0. The pig-iron was still made in the puddling furnace, and the iron formed into balls and treated with the hammer before passing to the mills.

..... The Kidwelly works were rebuilt in 1801 by Messrs Haselwood, Hathaway and Perkins, and a few years later passed to Messrs Vaughan Hay and Downman. In 1830, Hay, Thomas and Co were the owners, and in 1850 they were directed by H H Downman and Messrs Richet and James. Downman also had interests in the Carmarthen tinworks, for in 1838 there is reference to a lease to Messrs Henry Ridout Downman and H H Downman. In 1850 the Carmarthen tinworks passed to Wayne and Co.

..... Between 1850 and 1875 the iron industries heralded the tinplate and steel industries of the last half of the 19th century. South-east Carmarthenshire became a highly industrialised region. The early efforts of the iron-masters at the beginning and the pioneers of the Llanelly and anthracite coalfields had, long before, started a tradition of industrial development, which was further emphasised by the establishment in the area of other metallurgical industries and the complete development of the Llanelly Coalfield after 1850. After this date, other ironworks came into the area, and with the invention of new processes in the production of steel-bar, these ironworks turned to the manufacture of tinplates.

..... Between 1850 and 1870, when the non-ferrous industries reached their maximum development, numerous ironworks were established in and around Llanelly. In addition to the foundries, one or two of the ironworks had started making tinplates. Ironworking had been started in this area in the last decade of the 18th century and its resuscitation in the middle of the 19th century is significant for two reasons: (1) The ironworks started the tinplate industry and (2) The tinplate and steel industries replaced the languishing non-ferrous industries which had made the area so important since 1804.

..... Among the important factors contributing to the establishment of the ironworks were the coal supplies of the district; proximity to tidal waters; abundant supplies of fresh water, and relatively cheap sites on marshy ground near the docks.

..... The ironworks established in the Llanelly district around the mid century were as follows:•....Dafen. 1847

•....Morfa, 1851

•....Old Lodge, 1852

•....Marshfield (Western), 1863

•....Old Castle, 1866Each of these works had furnaces and forges. Most of them made tinplates, but one of them – the Old Lodge – made only bar-iron. The Morfa works were built in 1851 by Octavius Williams for John S Tregonning and Co. Two mills and a tinning plant were erected, and later Williams left to erect the Hendy works, near Pontardulais. In 1857, a forge was added for the manufacture of charcoal iron, and in 1872, two mills and a second charcoal forge were added, and other extensions carried out. In 1885, two steel furnaces were erected.

..... The Old Lodge Ironworks were built by Messrs William Nevill and J Thomas, but no tinplates were made until Morris started their manufacture there in 1880.

..... The Marshfield Ironworks were erected by Messrs Nevill, Everitt and Co in 1863, but closed down in 1879. In December the same year, the Western Tinplate Co was formed.

..... The Old Castle Iron Co was started in 1866 by Messrs Maybery, Thomas, Rosser and Samuel. These works made their own iron until 1886. The original two mills were built on the site of an early British fortification called Pen Castell, from which the works were named. 'Puddled coke' was mainly used for smelting. In addition to the Llanelly area, ironworks were established in the anthracite coalfield after 1838, and these were still important after the mid-century.

Date Where built Company Furnaces built Furnaces in blast 1868 Brynamman Henry Strick & Co 3 2 Gwendraeth Daniel Watney 3 – Amman Valley Amman Iron Co 6 (puddling furnaces) 3 (rolling mills) 1876 Amman Valley Amman Iron Co 7 (puddling furnaces) 3 (rolling mills When the Amman Valley works went over to tinplate manufacture they specialised in the making of blackplates, and this may be correlated with the long established iron industry of that valley. When the local blackband ore was used these ironworks were flourishing. When the utilisation of this ore was discontinued, new processes came into being which could not utilise the local low-content phosphoric ores, so that imported ores took their place after 1875. This marks the beginning of the establishment of steelworks along the seaboard."

2. The Tinplate and Steel Industries

The inventions of Siemens-Martin and Bessemer revolutionised the tinplate industry. Until about 1870, most of the iron made in the tinplate works of South Wales was either pig-iron or wrought-iron, made from pig-iron in a puddling furnace. It was from wrought-iron that steel was first made, though very occasionally. On account of the length of the operation, and the expense of steel, it did not come into general use. In 1851, Bessemer invented a method of making steel on a large scale, and therefore the cost of production was lowered. A second method of steel manufacture, the open hearth system, devised by Siemens and Martin in the works at Landore, near Swansea, was introduced at a later date. The steel industry became more and more dependent on imported ores, with the result that the centres of these industries became established on the seaboard. The main centres are at Llanelly, Swansea, Aberavon, and Briton Ferry.

..... It has been noted that after 1870 there were changes in the methods of manufacturing the raw material for the tinplate industry. The raw material of the industry before 1870 had been iron, made usually in charcoal forges, and puddling furnaces attached to the tinplate works. Just before 1875, the Bessemer method of steel manufacture was introduced, and Siemens produced a kind of steel suitable for rolling into tinplates. Eventually, steelworks were erected in the Llanelly and Swansea areas to produce Siemens steel; these steelworks worked as feeders to the adjacent tinplate works. From that time onwards, the tinplate manufacturers required tin bars (flat bars of steel) which led to a further concentration of the tinplate industry in the Llanelly and Swansea districts. Thus, in the peak year, 1891, there were twenty works (119 mills) in Carmarthenshire and fifty-one works (277 mills) in Glamorgan; and only eleven works (86 mills) in Monmouthshire.

..... Another reason for the concentration of the steel and tinplate industries on the seaboard was the heavy importation of the richer ores of Spain and other countries, bringing these heavy industries in close proximity to tidal waters.

..... An equally important reason for localisation was the presence of chemical industries in the region. The smelting of copper in the area had started one or two important side-industries, one of those being the manufacture of sulphuric acid. Large amounts of this acid are used in tinplate manufacture, and it could therefore be obtained at a relatively cheap rate. One other vital factor was the availability of fresh water. Water is indispensable to the tinplate industry, and in this region there are abundant supplies from rivers and artificial reservoirs. Finally, advantageous road and rail transport to the ports for export, and to the Midlands and London, where sheet, blackplates, and terneplates are largely used, is another advantage. In addition to the tinworks mentioned in the previous section, the following were also erected in south-east Carmarthenshire between 1866 and 1890;

Name of Works Owner Hendy Tinplate Works Broughton, Smith Llangennech Tinplate Works Thomas Harries St David's, Bynea Lord Glantawe South Wales, Llanelly Morewood, Rogers Glamorgan Tinworks, Pontardulais Webb, Shakespeare & Williams Morlais Tinplate Co (Llangennech) James Griffiths & Co Burry Tinplate Works (Llanelly) William Rosser Clayton Tinplate Works (Pontardulais) Jenkins, Bright & Williams Dynevor Tinplate Works, Pantyffynnon Williams, Stanford Raven Sheet & Galvanising Co, Glanamman Messrs Rees & Morris Aberlash Tinplate Works, Tirydail, Ammanford Messrs Elias, Phillips & Jones Ashburnham Tinplate Co, Burry Port Lord Ashburnham, Griffiths & Bevan The tinplate works situated in the interior (notably those at Pontardulais and in the Amman Valley) are in the actual zone of coal production, and are also favoured by low local rates, cheap fuel, and abundant water supplies. They suffer from higher transport costs and poor means of communication, often on branch lines, in marked contrast to the works on the seaboard, which are on the main lines. Furthermore, these peripheral works concentrate upon blackplate and not tinplate, and are therefore able to accept more specialised orders unacceptable to the larger works.

..... It is well to describe at this juncture the important changes witnessed in the modus operandi of tinplate manufacture during the 19th century. In 1829, scaling was done away with, and sulphuric acid was used for pickling. In 1829, Thomas Morgan introduced cast-iron annealing pots as a substitute for annealing in open furnaces. Black pickling was introduced in 1849 and steam was introduced into the vitriol bath by John Cann in the same year. The year 1866 witnessed a marked step forward, when Edwin Morewood (Llanelly) and John Saunders introduced what is familiarly known as the 'Morewood pot'.

..... As has already been noted, the substitution of Siemens soft steel (1875) and Bessemer steel (1880) inaugurated a trade of greater dimensions, which necessitated a more efficient organisation of the commercial aspect. In 1890 the 'washman' was relegated to the background by the introduction of patent tin-pots, and the century closed with the introduction of patent cleaning machines.

..... The rapid expansion in the tinplate industry from 1870 to 1890 was due in a large measure to the monopoly of nearly all the foreign markets enjoyed by the home producers. Previous to 1891, the United States bought 75% of the South Wales output of tinplates, a demand sustained by the use of hermetically sealed tin-can containers for the packing of fruits, meat, and fish. The use of terneplates (i.e sheets of thin steel or iron coated with an alloy of lead and tin) for roofing purposes increased the demand for South Wales tinplates from 1865 to 1895. In 1883 approximately 77% of the output of the 316 mills at work was annually exported to the USA. In this year the number of and the output of the works engaged in the manufacture of tinplates were as follows. (in the book is technical output data comparing Carmarthenshire and the rest of Wales).

..... The geographical distribution of the tinplate works in South-east Carmarthenshire in 1880 shows three well-marked concentrations:

(a) Around Llanelly, including Burry Port and Kidwelly. (b) The Pontardulais area, including Hendy and Llangennech. (c) The Amman Valley, including Pantyffynnon, Ammanford, Glanamman and Brynamman. The complete list (in 1880) included 14 works with a total of 65 mills;

Name of works Name of firm Total mills Avondale Avondale Tinplate Co 1 Burry (Llanelly) Burry Tinplate Co 4 Carmarthen Thomas Lester & Co 5 Dafen (Llanelly) Phillips, Nunes & Co 4 Glanamman (Cwmamman) Glanamman Tinplate Co 2 Gwendraeth (Kidwelly) J Chivers & Son 10 Hendy (Pontardulais) E Boughton & Co 2 Lion Tinplate Works H Thomas 2 Llanelly John S Tregonning & Son 4 Llangennech Llanegennech Tinplate Co 8 Morlais (Llangennech) Llansamlet Tinplate Co 2 Old Castle, Llanelly Old Castle Iron & Tinplate Co 6 South Wales Llanelly E Morewood & Co 9 Western Llanelly Western Tinplate Co 4 In connection with the ports that were exporting tinplate, it is important to note that Liverpool was the first in importance, with the Bristol Channel ports – Cardiff, Swansea and Llanelly – coming next. The great market up until 1890 was the USA, so that Liverpool merchants sent their tinplates to the States on the American liners. In the closing years of the century, the rapid developments in the South Wales coalfield, and the localisation of the chemical industries in the Swansea and Llanelly districts, resulted in many of the tinworks in Monmouthshire and West Carmarthenshire being abandoned and also the transference of the export trade in tinplates from Cardiff to Swansea. (Exports from Swansea increased from 12,420 tons in 1878 to 418,725 tons in 1890).

..... The South Wales tinplate trade suffered a hard blow in 1890 when the McKinley tariff came into operation. This signified the end of the export of Welsh tinplates to the USA, and the beginning of the American tinplate industry. In spite of this the South Wales tinplate trade continued to flourish, and in 1910 approximately 370,360 tons of tinplates and blackplates were exported from the ports of South Wales to the Far East, Argentine, Brazil, Canada and France.

..... We have already seen that most of the tinworks had interests in the new steelworks, because the raw material of the tinplate works was now the steel bar. A still closer association is the distinctive feature of the post 1891 period, but before we proceed to describe this it should be noted that the Carmarthen tinplate works continued to produce tinplate until 1900. The site of these works was on the spot where the early furnaces and forge were built by Robert Morgan. In 1850, the tinplate works were taken over by Messrs Wayne and Co, who specialised in the manufacture of blackplates. From 1868 until they were closed down in 1900, they were carried on by Thos Lester and Co. This was one of the earliest tinworks in the county, and in 1820 had two mills each composed of two pairs of rolls, worked by five men. The weekly production was 464 boxes and the tinplates were sold to markets in Liverpool, London, Bristol and Glasgow. The iron ores were imported from South Wales and Lancashire, and the pig-iron was made from a mixture of these ores – this mixture having been found to produce 'a metal plate of such pliability as the iron-plates designed for tinning require'. These tinworks were a natural development from the forge at Carmarthen, but were able to carry on until 1900, in spite of the fact that larger and more modern works were built in the Llanelly area. There were abundant water supplies at Carmarthen, the coal was imported along with the ores, and for the first half of the century a fairly steady demand for a special type of plate for the French market kept the works going very successfully.

..... After 1900, with the greater advance of American competition and the large imports of American and Continental steel and iron bars at a cheap rate, the Carmarthen works eventually closed down. The works were away from the ports of the south-east of the county and could not compete for orders with the coastal works, and thus there ended a great tradition of iron and tinplate manufacture extending over a period of 150 years.The following steel and tinplate works were erected in the period 1891-1912;

Name of works Proprietors Date The Welsh Tinplate & Metal Stamping Co The Welsh Tinplate & Metal Stamping Co 1897 The Llanelly Steel Co (1907) Ltd, Llanelly Messrs Briton Ferry Steel Co; The Old Castle Tinplate Co; The Western Tinplate Co 1898 The Wellfield Galvanising Co Llanelly As Above 1908 Glynhir Tinplate Co, Pontardulais As Above 1910 Dulais Tinplate Co, Pontardulais As Above 1911 The Pemberton Tinplate Co, Llanelly As Above 1911 The Gorse Galvanising Co, Dafen, Llanelly As Above 1911 The Bynea Steelworks, Llanelly As Above 1912 South Wales Steelworks Llanelly R Thomas & Co, eight new mills erected in – 1911 The development of the steel and tinplate industries in the Llanelly area after 1900 is intimately bound up with the importation of foreign steel and iron bars, produced at a cheaper rate in America and the Continent. Another outstanding feature was the extent to which various groupings took place among tinplate and steel works, i.e amalgamations between steel and tinplate works. This feature is a further factor in industrial development in recent years, because the steelworks specialise in the production of steel bars from pig and scrap iron for sheet and tinplate manufacture, imported at Llanelly and Burry Port. In order to appreciate these changes, evidence must be drawn from the entire metallurgical area in SW Wales. This is roughly the region contained within the triangle formed by the towns of Port Talbot, Burry Port and Ystradgynlais. Within this area there are fourteen steel works capable of an annual output of 2,800,000 tons pa. In the tinplate trade also grouping has taken place to such an extent, that of 480 mills in the trade, 389 or 81% are covered by groupings.

..... The controlling body of this triangle is the South Wales Siemens Steel Association, formed in 1906, having within its membership eight firms owning and controlling fourteen steel works. The Llanelly and district works in the Association are the Llanelly Steel Co Ltd; Messrs Richard Thomas & Co Ltd; and the Bynea Steelworks Ltd. Several Llanelly tinplate works had interests in the Llanelly Steelworks, eg Dafen Tinplate Works and The Old Lodge Tinplate Works.

..... In 1923 the South Wales Tinplate Corporation Ltd was registered which represented a selling organisation for (a) Richard Thomas and Co Ltd (who own six works in Carmarthenshire); (b) Kidwelly Tinplate Co Ltd; (c) Ashburnham Tinplate Co Ltd, Burry Port; (d) The Old Castle Iron and Tinplate Co Ltd, Llanelly; (e) The Western Tinplate Works Ltd, Llanelly. The last four works resigned from the Corporation in 1931.

..... Throughout the new century the deep-rooted tradition of production for export held the field but slowly tinplate manufacture was forced to become more diversified in character to meet the increasing demands of the home market. The growth of the automobile industry kept the tinplate trade well occupied until 1914. In addition to the manufacture of tinplates, blackplates and galvanised sheets, one firm – the Llanelly Metal Stamping Co – started manufacturing enamelled hollow ware. This industry makes such articles as basins, buckets, and bowls from sheet metal or steel usually by stamping and then coating with enamel.

..... Between 1920 and 1930 the steel and tinplate industry had to face serious competition with foreign countries, such as Belgium, France, and Germany, who exported steel bars at 15s per ton less than Welsh steel bars. Foreign bars have literally been 'dumped' into Welsh ports and large quantities have been used by tinplate manufacturers.

..... The steelworks produce steel ingots from imported pig-iron and scrap. The quantity of scrap smelted is over twice that of pig-iron and is obtained from the Midlands and the shearings and 'wasters' from the tinplate works. The transport costs of the scrap iron contribute to the high cost of home steel bars, hence the reason for the large import of foreign bars. Some protective measures for these industries were therefore vital and were forthcoming after 1930.

..... At the same time new methods of manufacture were making headway, chief of which has been the manufacture of tinplate by the strip mill method. This is, in the main, an American development, and the tonnage produced by this method is rapidly increasing year by year. The major variations are mechanised mills, reversing strip mills, production of steel plates electrolytically, electrolytical tinning, and the production of the continuous narrow strip of tin only a few inches wide for direct manufacture of car bodies.

..... The increased demand for steel sheets in the motor industry, together with the development of the canning industry and the demands for heavy steel in rearmament programmes, have made a marked change for the better in the fortunes of the steel and tinplate industries during the third decade of the present century. The full range of the diversified character of the modern period can be gathered from the fact that one Llanelly brewery – the Felinfoel Brewery Co – has commenced canning beer. The tinplate is obtained from the St David's Tinplate Co, Llanelly, and the lacquered containers made by the Metal Box Co for the firm. Other works in the region supply the home market with tinplate to firms such as Heinz, to biscuit manufacturers at Reading, and to the fruit-canning factory opened at Worcester in 1930. In 1932, the Gorse Tinplate Works, Llanelly, started to make building requisites, such as gutters, rain-water and drain pipes from sheet metal, which is welded and coated with a special kind of vitreous enamel in several colours. This product is called Vitreflux, which, owing to its power of withstanding weather conditions is now in steady demand on the market. Thus since 1932 the home market for tinplates in Britain has consumed an ever increasing proportion of the total output. In that year it amounted to 35.61 % of the total output; in 1933 37.9%; 1934 42.26%; 1935 47.33%; and in 1936 it reached 51%, thus for the first time outstripping the proportion exported."3. The Anthracite Coal-Mining Industry

Up until 1800, the mining of anthracite coal had been limited to 'scourings' on the outcrops, and there was no deep mining. It was not until about 1815 that the steam engine was introduced into the Gwendraeth Valley and real coal mining started in earnest. Before the time of the steam engine and the opening up of the mines on a large scale, anthracite coal was used for lime-burning. This had been carried on even in the very early part of the 18th century, when wood was normally used as a fuel in lime kilns.

..... After 1800, however, anthracite coal was used to a greater extent for lime-burning. The canals and tram-roads brought the coal and limestone of the Llandebie and Gwendraeth areas into the ports. An interesting survival of this practice was the export of Llandebie lime to South Africa via Llanelly for the purpose of sugar refining at the close of the 19th century. Generally speaking, however, although new pits were opened in the anthracite coalfield during the first part of the 19th century, the industry exhibited no great expansion, although new avenues of utilisation were found.

..... Kymer's colliery has already been noted, and between 1824 and 1830 collieries were in operation at:

• Floy Farm owned by Captain Scott, at Tynywern and Tynywaun, Ponthenry, the latter owned by J Arthur. • at Old Pentremawr, Pontyberem, owned by Elkington. • at Old Cae-Pont-bren, Pontyates, owned by Herbert Lloyd. • and at Cross Hands, under the ownership of Colonel Wray and Norton • Messrs Christopher and Jones opened the following pits at Gorslas; Gilfach pit, Millers pit, George pit, Pwllylledrim pit. These collieries were described as 'prosperous little concerns' and the output was about 100 tons a day. The coal from Cross Hands and Gorslas was conveyed to the Llanelly 'docks' by means of Raby's tram road (the Carmarthenshire 'railway'). Raby was also the first iron master to venture the use of anthracite coal for smelting, although his efforts met with limited success. ..... Between 1800 and 1850 the coal was mainly used for malting, hop-drying, and lime-burning. Small quantities were exported, especially after 1841, when the railway was opened from Llanelly to the Amman Valley. The development of the coalfield after 1865 is closely related to extension in the demand for this type of coal by foreign countries. In 1868 France imported 14,369 tons and Italy 558 tons; by 1921 these figures were 848,297 tons and 238,474 tons respectively. In addition, the number of foreign customers had risen from two to seventeen in the same period.

..... By the middle of the 19th century technical inventions enabled deep mining to be carried on at a time when foreign demand increased. This demand in its turn depended on other inventions, such as the anthracite burning stove of the Baltic lands about 1880, as well as on large scale advertising organised by Frederick Cleeves, 'the father of the anthracite industry', who introduced the coal to the continental consumers. Between 1887 and 1902 the output of Welsh anthracite increased by 287% and 50% of this was absorbed by the export trade.

..... The most important buyers of anthracite are France, Italy, Germany, the Low Countries, Norway and Sweden, the USA, the Argentine, and the little island of Guernsey, which imports 200,000 tons for its hot-houses alone.

..... A mild winter on the continent may cause a fall in the imports, as very much less would be needed for central heating purposes. Again, good harvests in Europe affect the return cargoes of ships taking coal to Canada, USA, and South America from South Wales ports. An important feature of the anthracite export trade between 1913 and 1930 was the tremendous growth in the Canadian trade. In 1913, 48,000 tons were exported to Canada; in 1930, 975,000 tons. Ice on the St Lawrence river retards the anthracite export trade during the winter months. The excellence of its quality – the best in the world according to a well known authority – and the enormous reserves – over 6,000 million tons in 1904 according to the Lord Merthyr report – all help to enhance the export trade.

..... Before 1800 the leading port in South Wales for the export of anthracite was Milford. Afterwards with the development of communications facilities around Llanelly, this port supplanted Milford. After 1880, with the greater development of the coalfield and the opening up of foreign markets, Swansea took the place of Llanelly as the great exporter of anthracite coal.

..... The results of this foreign demand emphasised the need for the proper and efficient preparation of the coal for the market. The entrepreneur himself was obviously too busily occupied with the opening of new works, so that the marketing problem was taken over by a selling agent, whose contribution to the South Wales anthracite coal trade has been very great. In America, anthracite was graded into commercial types in order to meet different users. Similarly Welsh anthracite was graded and crushed into different types by special crushing, screening, and washing plants, and this, of course, involved the use and investment of more capital in the industry. The old and shallow workings of the early period were in the main closed down. New collieries were opened, tapping deep seams; better machinery was introduced, and electricity was used. The individual owner or entrepreneur gave way to the company who, with more capital and energy, opened better-equipped collieries. This created a great demand for labour, which up to 1900 was only moderate, because of the time that elapsed before the new mines could develop fully. After this, progress was rapid.

..... The following figures bring out very clearly the development of the industry between 1890 and 1930, obscuring, of course, the troubled conditions from 1914 to 1918:

Year Total Output, Tons 1890 1,221,000 1900 2,204,000 1910 4,032,000 1920 4,231,951 1930 5,568,238 Depending as it was on its foreign customers, the anthracite coal industry suffered a great shock during the war period through the dislocation of the market. Up until 1917 the industry was badly hit, but from 1917 to the end of government control in March, 1921, it greatly retrieved its position. What the government actually did during this period was mainly to stimulate the home demand for anthracite. Its use was extended mainly by the use of anthracite stoves and central heating appliances. In 1917, 2,123,000 tons were consumed, and in 1920, 2,604,000 tons. After 1921 the anthracite industry continued to expand, and in 1923 4,873,000 tons were produced – the highest figure in its history until 1930.

..... The development of large-scale organisations in the anthracite industries did not reveal itself until the early decades of the 20th century. In 1903, an attempt was made to establish a combination in the anthracite coal district, but this was wrecked by the difficulty of valuation. In 1905, the idea of an anthracite coal trust was revived. During these two years, a period of depression in the industry accentuated the materialisation of the idea. Certain firms were invited to form the proposed amalgamation, but the prices they demanded for their properties were prohibitive. Once again, valuation shattered the project. In 1911, amalgamation was again discussed, but it did not advance beyond that stage until the post-war period.

..... Then, in 1923, came the formation of the Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries, Ltd. On its formation it acquired the whole of the issued capital of the Cleeves Western Valley Anthracite Collieries, Ltd, which owned four collieries in the anthracite area and held practically the entire share capital of the Gelliceidrim Collieries, Ltd; also the share capital of the Gurnos Anthracite Collieries, and the Cawdor and Cwmgors collieries were acquired. Its capital at the time of its formation amounted to £2,500,000. In the same year (although the prospectus was not issued until June, 1924), the United Anthracite Collieries, Ltd, was formed. The United Anthracite Collieries, Ltd acquired and developed the Great Mountain Anthracite Collieries (including the business of Waddell & Sons, London and Llanelly), the Ammanford Anthracite Collieries, the Pontyberem Anthracite Collieries, and the New Dynant Anthracite Collieries. The Amalgamated Anthracite Collieries, Ltd had an output capacity of about 750,000 tons, and the United Anthracite Collieries Ltd, approximately 600,000 tons.

..... On the other hand, the highly organised protective machinery of the miner is the Miners' Federation of Great Britain. This is composed of some score of constituent trade unions, some of which, such as the South Wales Miners' Federation, had originally a federal structure. The anthracite area of Carmarthenshire and west Glamorgan was known technically as Area No 1. Anthracite wage conditions are determined by the South Wales Conciliation Board.1.....Aberlash

2.....Ystalyfera's Philanthropist — the rags to riches life of David Davies

3.....A History of the Iron, Steel and Coal Industries in Carmarthenshire